The Power of a Well Written Letter

With so many means of (effectively instant) communication available to us today, we hardly consider a letter particularly relevant. TV, radio and internet bring us news of the world, often delivered it right to our hand via a newsfeed. Phone, email, social media, and a variety of instant messaging applications keep us connected to those we want to keep in touch with (and sometimes those we’d rather not.)

During the Regency era, letters were a major source of news and communication, both personal and in the broader social context. Interestingly, most of this communication flowed through the pens of the women of a household.

Role of Regency Letters

A person who can write a long letter with ease, cannot write ill.

~Jane Austen

Typically, women wrote letters in the morning, before breakfast. They kept track of the letters they received and to whom they owed letters as carefully as they tracked other important social obligations, like dinner invitations and entertaining. Notes in diaries and even formal lists helped them to organize of the letters they needed to write. In some ways, this feels rather similar to the modern practice of flagging emails to remember to respond to them. The more things change, the more they stay the same, right?

Writing was a complex subject that would be an explicit part of a girl’s education. At boarding school, if she was privileged to attend one, or from her governess or mother if she was educated at home, writing lessons included penmanship—beautiful handwriting was a valued accomplishment (one at which I would have failed, miserably)—orthography, otherwise known as spelling (another subject at which I falter), and the art of letter writing, including how to open and close their letters with suitable phrases. The latter often meant copying such suitable phrases out of a book provided for such use, another school assignment I dreaded like no other. So far, I’m batting zero for three at being an accomplished Regency era woman.

Private or Public

Since letters were frequently shared among one’s social circle, the emphasis on suitable phrasing and content makes a certain amount of sense. The ideal letter style avoided both formality and vulgarity, striking a proper middling tone.

Obviously, not all letters were intended for public consumption. Select portions of letters might be read aloud to an audience. Sometimes, the correspondent would indicate what could be read aloud by underlining the passage. Otherwise, letters were considered very private and kept in locked boxes and drawers to preserve them from prying eyes.

Different styles of letters were written to suit the particular need for writing.

Letters of ceremony

Ladies’ letters took two primary forms, formal letters of ceremony and informal personal letters.

What were letters of ceremony? Much like formal visits, these were letters that were expected on particular occasions. Births, deaths, and weddings and the like occasioned such letters. These letters often had to be written quickly. For example, information about a death was dispatched as fast as possible to permit people to attend the funeral, in such case, being able to copy a pre-written letter would be a real boon.

Appropriate and elegant composition was expected in letters of ceremony and the return correspondence that followed. But how to ensure just the right tone would be struck? Never fear, books like “The Complete Letter-Writer; or, Polite English Secretary” (London, 1789) were available with a collection of model letters one could copy and modify to suit the occasion.

While today’s etiquette would find a largely plagiarized letter of congratulation or condolence largely insulting and offensive, during the Regency those same letters would be regarded as kind and thoughtful. All a matter of perspective, I suppose.

Correspondence as an extension of conversation

I have now attained the true art of letter-writing, which we are always told, is to express on paper exactly what one would say to the same person by word of mouth.

~Jane Austen, letter to Cassandra

Austen’s sentiment reflected a common perspective of the day. Informal, personal letters were an extension of the art of conversation and should ideally create the same sort of experience as good conversation.

Even so, there were expected courtesies to be followed. Before one could begin to converse, etiquette required a commentary on news shared in prior correspondence, sometimes at significant length. After that, daily news and family information would take priority over other topics.

Once the important news was shared, letters could turn to more pleasant topics. Since personal letters should make the receiver feel loved, honored and respected, unconstrained displays of affection were appropriate. News of fashion, travel, and for men, sports, often took up the remaining page space. The works of popular artists, their lives, homes and works, also provided excellent fodder for personal letters.

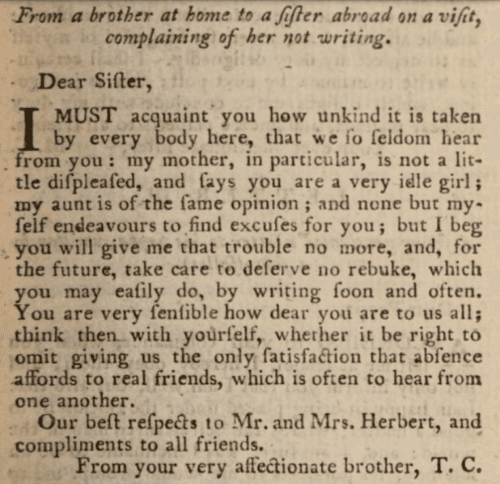

Of course, if one found themselves at loose ends for what to write in a personal letter, the Complete Letter-Writer was there to lend a hand. The first sample letter in the section ‘Miscellaneous Letters on the most useful and common occasions’ is this (right)

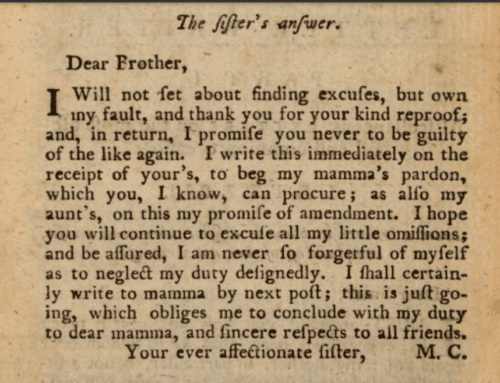

To which the Complete Letter Writer also supplies a handy response. (Left)

Unexpected points of etiquette

The Complete Letter-writer also provides us with some additional, and to me at least, unexpected points of etiquette while writing a letter to a social superior, including

- Use quarto (large size) sheets of fine gilt paper and enclose it in a second sheet of paper, (a practice which would incur additional postage.)

- Leave large top, side and bottom margins in the letter, not typically done when writing a letter to an equal.

- Avoid post scripts for they are considered too informal. Similarly avoid leaving out letters in words or using contractions.

- Keep the letter as short as your subject will permit, especially when asking for favors.

- Use proper full stop (period) at the end of every paragraph to make your meaning clear.

- Sign your name in a larger hand that the body part of your letter.

For letters written to equals or inferiors, these rules largely do not apply. Long effusions of flowery affection, capricious shortening of words, irregular margins, and a variety of techniques to fit as much as one possibly could on a single sheet of paper were acceptable.

We’ll detail these in the next installment.

References

Collins, Irene. Jane Austen, The Parson’s Daughter. Hambledon (1998)

Copeland, Edward, McMaster, Juliet, The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Durrant, Jacqui. How to Write a Letter, Gold Rush Style. Life on Spring Creek. November 28, 2017. Accessed June 9, 2023. https://lifeonspringcreek.com/2017/11/28/how-to-write-a-letter-gold-rush-style/

Lane, Maggie. Jane Austen’s World. Carlton Books (2005)

Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. Harry N. Abrams (2002)

Martin, Joanna . Wives and Daughters. Hambledon Continuum (2004)

Selwyn, David . Jane Austen & Leisure The Hambledon Press (1999)

The Complete Letter-Writer. W. Darling: Edinburgh. 1778.

Todd, Janet M., Jane Austen in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Watkins, Susan. Jane Austen’s Town and Country Style Rizzoli (1990)

‘Sign your name in a larger hand [than] the body part of your letter.’ Think John Hancock on the Declaration.

Back in the day [60s], in middle school, we had a class where we practiced penmanship with a nip pen and ink. You can’t tell by my handwriting today that I was ever within a mile of a penmanship class. We also learned the art of letter writing. Again, I have fallen way short of any etiquette stipulated in your post.

This was a fun post that brought back fond [or horror] memories of days gone by. LOL!

Thanks for sharing

Pingback:In Her Own Hand - Random Bits of Fascination