Georgian Ice Cream and Ices

Another blast from the past AND a special free sale!

After making its way onto the culinary scene, ice creams and sorbets exploded in popularity during the Georgian era. But Georgian ice cream looked a little different from its modern counterpart. Come take a peek!

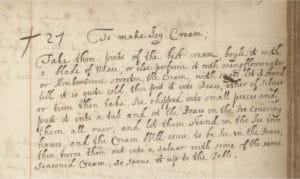

The first known recipe for true (dairy-based) ice cream was found (unpublished) in the diary of Lady Anne Fanshawe, an English memoirist. The recipe was written around 1665 under the name icy cream. (Kraft, 2014) You might notice some interesting ingredients for flavoring including orange blossom water, mace, and ambergris, (a waxy substance produced in the gut of whales.) Honestly, between you and me, I can’t imagine what it must have tasted like.

Here’s her recipe, with original spellings:

To make Icy Cream

Take three pints of the best cream, boyle it with a blade of Mace, or else perfume it with orang flower water or Amber-Greece, sweeten the Cream, with sugar let it stand till it is quite cold, then put it into Boxes, ether of Silver or tinn then take, Ice chopped into small peeces and putt it into a tub and set the Boxes in the Ice covering them all over, and let them stand in the Ice twohours, and the Cream Will come to be Ice in the Boxes, then turne them out into a salvar with some of the same Seasoned Cream, so sarve it up at the Table

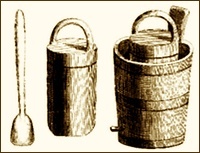

In the early days of ice cream making, confectioners were uncertain about freezing techniques, worrying about how much ice they needed, the how much salt to mix with the ice, and—perhaps most significantly—how keep the salt out of the ice cream. Beyond all that, they were concerned about storage and drainage, problems endemic to the days before refrigeration. Flavor, on the whole, seemed less important than freezing. (Quinzio, 2002)

Freezing Ice Cream Before Refrigeration

Early recipe books focused a great deal of attention to the freezing process. Eale’s 1718 treatise is typical, suggesting you take any sort of cream you like, then detailing how to freeze it.

To Ice Cream.

Take Tin Ice-Pots, fill them with any Sort of Cream you like, either plain or sweeten’d, or Fruit in it; shut your Pots very close; to six Pots you must allow eighteen or twenty Pound of Ice, breaking the Ice very small; there will be some great Pieces, which lay at the Bottom and Top: You must have a Pail, and lay some Straw at the Bottom; then lay in your Ice, and put in amongst it a Pound of Bay-Salt; set in your Pots of Cream, and lay Ice and Salt between every Pot, that they may not touch; but the Ice must lie round them on every Side; lay a good deal of Ice on the Top, cover the Pail with Straw, set it in a Cellar where no Sun or Light comes, it will be froze in four Hours, but it may stand longer; than take it out just as you use it; hold it in your Hand and it will slip out. When you wou’d freeze any Sort of Fruit, either Cherries, Rasberries, Currants, or Strawberries, fill your Tin-Pots with the Fruit, but as hollow as you can; put to them Lemmonade, made with Spring-Water and Lemmon-Juice sweeten’d; put enough in the Pots to make the Fruit hang together, and put them in Ice as you do Cream.

Following her instructions produces a solid lump of iced cream, rather unlike anything we would eat today—or possibly be interested in eating given the lack of attention to flavor.

By the 1770’s improved directions—separate form recipes for actual ice cream flavors—suggested stirring the mixture as it froze to maintain a pleasing texture.

The Way To Ice All Sorts Of Liquid Compositions.

WHEN your composition is put in the sabotiere take some natural ice and put it in a mortar, when it is reduced into a powder strew over it two or three handfuls of salt ; then take your pails, put some pounded ice in the bottom, and place your sabotiere in those pails which you fill up after with ice to bury the sabotiere in.

You must take care in the beginning to open your sabotiere in order not to let the sides freeze first, and on the contrary detach with a pewter spoon, all the flakes which stick to the sides, in order to make it congeal equally all over in the pot.

Then you must work them well as much as you are able, for they are so much the more mellow as they are well worked; and their delicacy depends entirely upon that. You must not wait till they are thoroughly iced to begin to work them, because they would become too hard and it is not possible to dissolve what js congealed in lumps or pieces. When you see they are well congealed you let them rest, taking care for this time there should be some which stick to the sides of the icing-pot: this will prevent them from melting and make them keep longer in a right degree of icing. (Borella, 1772)

By the nineteenth century, specialty books on ices and ice cream offered even more specific instructions:

Observations on Ice Cream.

It is the practice with some indolent cooks, to set the freezer, containing the cream, in a tub with ice and salt, and put it in the ice-house; it will certainly freeze there, but not until the watery particles have subsided, and by the separation destroyed the cream.

A freezer should be twelve or fourteen inches deep, and eight or ten wide. This facilitates the operation very much, by giving a larger surface for the ice to form, which it always does on the sides of the vessel; a silver spoon, with a long handle, should be provided for scraping the ice from the sides, as soon as formed, and when the whole is congealed, pack it in moulds (which must be placed with care, lest they should not be upright,) in ice and salt till sufficiently hard to retain the shape–they should not be turned out till the moment they are to be served.

The freezing tub must be wide enough to leave a margin of four or five inches all around the freezer when placed in the middle, which must be filled up with small lumps of ice mixed with salt–a larger tub would waste the ice. The freezer must be kept constantly in motion during the process, and ought to be made of pewter, which is less liable than tin to be worn in holes and spoil the cream by admitting the salt water.” (Randolph, 1824)

Early Ice Cream Flavors

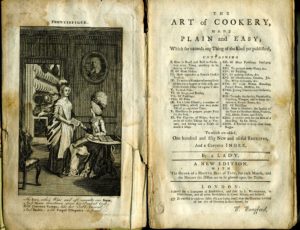

By the late seventeen hundreds into the early eighteen hundreds, the freezing process was well enough established to really focus on flavors. A perusal of cookbooks from the eighteenth and early nineteenth century suggests that fruit flavors were probably the most popular of ice creams. Hannah Glasse (1747) offered a typical recipe (and one that later appeared in a number of other cookbooks thanks to lack of copyright protections, but that’s another story…)

To make Ice-Cream.

PARE and stone twelve ripe apricots, and scald them, beat them fine in a mortar, add to them six ounces of double-refined sugar, and a pint of scalding cream, and work it through a sieve; put it in a tin with a close cover, and set it in a tub of ice broken small, with four handfuls of salt mixed among the ice. When you see your cream grows thick round the edges of your tin, stir it well, and put it in again till it is quite thick; when the cream is all froze up, take it out of the tin, and put it into the mould you intend to turn it out of; put on the lid, and have another tub of salt and ice ready as before; put the mould in the middle, and lay the ice under and over it; let it stand four hours, and never turn it out till the moment you want it, then dip the mould in cold spring-water, and turn it into a plate. You may do any sort of fruit the same way. (Glasse, 1747)

In theory any cream or custard recipe could become an ice cream, which offered any number of wild sounding options which sound more modern than Georgian: avocado, eggplant, lavender, rose petals, crumbled macaroons, caramel, ginger, lemon, tea, anise seed, chervil, tarragon, celery, parsley, cucumber, asparagus and parmesan cheese!

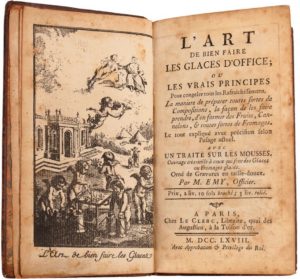

Emy’s 1768 book devoted to ice cream—L’Art de bien faire les glaces d’office; ou Les vrais principes pour congeler tous les rafraichissemens—includes instructions to make rye bread ice cream. He added rye bread crumbs to a basic ice cream mixture, let it thicken, and then strained the mixture before freezing. Brown bread ice cream recipes (which believe it or not are still made today) followed in other confectionary books along with ice creams made with macaroons and various other cookies. Interestingly, these were all strained to produce a smooth product, quite the contrast from today’s ice creams filled with crunchy and chewy bits.

Chocolate, coffee, and tea, the three important luxury beverages of the era made their way into the dessert world as well. Cookery books contained recipes to make sweet dessert creams with all three. Emy then converted those into chocolate and coffee ice creams, mousses, and ices. He suggested adding ambergris (whose flavor I am told ranges from earthy to musky to sweet), cinnamon, vanilla, clove, or lemon for additional flavor. (Jeri 2009)

So what were some of the more unique period flavors? Stay tuned and I’ll be sharing some of my favorites, including asparagus, spinach and oyster!

Pingback:Holiday Entertaining~Card Parties - Random Bits of Fascination