To be an Officer and a Gentleman

To be an Officer and Gentleman

Jane Austen’s writing includes many military men: Colonel Brandon, Colonel Fitzwilliam, Captain and General Tilney, Lieutenants Wickham and Denny. In her tales make note how these men purchased their commissions, but what was the motivation for doing so and how did the process work?

Being an officer made you a gentleman

In the Regency era, social status was closely related to career and wealth. An Army officer or Navy officer was considered a gentleman. Thus a man could gain an element of “respectability” that they might not hold by virtue of their birth. Moreover an officer’s status was considered higher than that of other gentlemanly professions: the church, the law and medicine.

Why were commissions purchased?

Modern sensibilities tend to be uncomfortable with the concept of buying a commission. In the Regency era, the system was viewed differently. They believed that since men had to pay for their rank, men of fortune and character that had a real interest in the fate of the nation would be drawn to the military.

Moreover, since they ‘owned’ their commission, they would be more responsible with their ‘property’ than someone with nothing to lose. Private ownership of rank also led to perception that since officers did not owe their rank to the King, they would be less likely to be used by the King against the people.

Purchase of commissions also served a practical purpose. The price paid for a commission served as a sort of nest egg for the officer, returned to him when he ‘sold out’ and retired. Thus there was no need to provide pensions for retiring officers.

Purchasing a commission R

eforms set in place by the Duke of York in 1796 set in place certain requirements for potential officers. Candidates had to be between the ages of 16 and 21 years of age, able to read and write and vouched for by a superior officer. Once these were fulfilled, the required sum of money would be deposited with an authorized Regimental Agent who would submit the applicant’s documentation for approval. Depending on the regiment, officers began their careers at a ‘Subaltern’ rank of Ensign, Second Lieutenant or Coronet.

How much did a commission cost?

Commissions were expensive, full stop. One had to be wealthy or have wealthy friends from which to borrow in order to afford a commission. Prices varied depending on the regiment and rank. (Keep in mind the reference point of £50 a year as minimum wage.) Subaltern rank ranged in price from £400 with the Infantry to £1050 with the Horse Guards. Lieutenant Colonel ranged from £3500 to £4950. When an officer served long enough to be eligible and wished to purchase a promotion to the next level of rank, he would pay the difference between his current commission and the next rank.

After 1795, a Subaltern (Lieutenant and below) had to serve at least three years before becoming a Captain; at least seven years in service (two as Captain) to become a Major; and nine years in service to be a Lieutenant-Colonel. Advancement above the rank of Colonel was by seniority only. Advancement was only possible if there were vacancies in the desired ranks and junior officers could spend several years without advancing.

Gaining a commission without purchase

If an individual could not afford a commission, there were non-purchase ways of obtaining a commission. A man could become a “Gentlemen Volunteer.” To do so, he would apply to the Commanding Officer of a regiment to serve at their own expense in the hope of filling a non-purchase vacancy when (and if) it occurred. It was also possible for a man to be promoted from the ranks due to valor or meritorious service. The death, disability, or retirement, of another officer might create a vacancy that needed to be filled immediately. Other openings came with the establishment of new Regiments, or the expansion of existing ones. These alternatives were much more common in times of war.

The Militia-A Different Breed of Officer

Austen’s Pride and Prejudice includes a military regiment temporarily stationed in Meryton. These men are members of the militia, not the regular army (discussed in the last post.) While at first blush, there may seem little difference between the regular army (the Regulars) and the militia, the differences are striking and significant.

What was the Militia?

The militia served as a peace keeping force on home soil. History had taught that a regular army could be a great threat to civil liberties, so the virtues of the militia were sometimes overstated. In theory, they suppressed riots, broke up seditious gatherings and if needed, repelled invading enemy forces. Unfortunately, the militia was a dubious peacekeeper. It was not uncommon for its members to sympathize with their rioting neighbors they were sent to subdue. Moreover, their lack of training made them amateurish compared to the regulars.

Joining the militia

Parliament controlled the size of the militia. Though considered a volunteer force, all Protestant males were required to make themselves available for militia service. The King required the Lord-Lieutenant,

usually a local nobleman, each county to gather a force of able-bodied men between 18 and 45 years of age to fill the quota for his area. Militia service required a five to seven year commitment to service on home soil with no chance of being sent overseas. Only clergymen were exempt from service.

If a man did not wish to serve he could pay a substitute to serve in his stead. The going rate started at £25. (Keep in mind our comparison of a minimum wage job bringing in £50 a year.) Most militia officers were drawn from the local gentry and were led by a colonel who was a county landowner.

Officer’s commissions were not purchased as they were in the regular army. Officer ranks was directly related to the amount and value of property they or their family held. For example, to qualify for the rank of captain a man needed to either own land worth £200 per year, be heir to land worth £400 per year, or the son of a father with land worth £600 per year. A lieutenant needed land worth £50 a year.

In practice it was difficult to find officers, particularly lower grade officers, for militia service. So the property qualifications for lieutenants were often ignored. It was in this way that George Wickham could become an officer despite not having a property owner in his family. While this leniency allowed many to join the ranks of officer who would not otherwise have such an opportunity, it did bring down the perceived status of the militia officer.

Life in the militia

Service in the militia carried little threat of front line duty. Officers had a great deal of leave and often enjoyed a busy social schedule provided by the local gentry. Since all officers were supposed to be property holders of some measure, they were all considered gentlemen and afforded the according status.

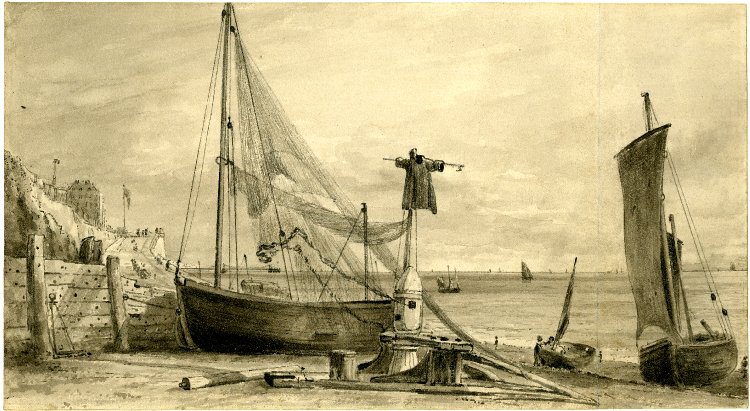

In summer the militia’s regiments went into tented camps in the open countryside to engage in training exercises. Camps were located throughout the southern and eastern coasts, the largest at Brighton. Military reviews, held on open hillside or common land, made thrilling entertainment for the local residents. They included displays of marching, drilling, firing at targets and even mock skirmishes often for the benefit of a visiting general. In the winter, the militia quartered wherever accommodation could be found for them in the nearby towns and villages. Accommodations were paid for by the soldiers themselves.

Public attitude toward the militia

All in all the militia was not popular. Inhabitants resented assessments of equipment and money to cover the needs of the militia. Men resented being drafted to serve and were apt to do everything they could to avoid their military training.

As a peacekeeping force, they militia had little to do but drill. With so much free time on their hands, they developed a reputation for a wild lifestyle of parties and frivolity. Since the militia moved often, officers had a great temptation to run up bills and leave without paying them. As a result innkeepers and tradesmen disliked them and often protested the militia quartering in or even passing through their town. Not surprisingly, parents often saw militia officers as a threat to their marriageable daughters since their families were unknown and might disappear from the neighborhood very quickly.

Click here to read more about officers in the Regency Era.

Click here to read more about Gentlemen in the Regency Era.

Click here to go to the Regency Index.

References

A Background on War. Regency Collection: Boyle, Laura.(2001) Jane Austen Centre On Line Magazine.

Advancement in the British Army Boyle, Laura.(2001) Jane Austen Centre On Line Magazine.

Collins, Irene. (1998) Jane Austen, The Parson’s Daughter . Hambledon Press.

Day, Malcom. (2006) Voices from the World of Jane. Austen David & Charles .

Downing, Sarah Jane. (2010). Fashion in the Time of Jane Austen. Shire Publications

Entry into the Officer Corps Boyle, Laura.(2001) Jane Austen Centre On Line Magazine.

Holmes, Richard. (2001). Redcoat, the British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket W. W. Norton & Company

Le Faye, Deirdre. (2002). Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. Harry N. Abrams

Militia. Regency Collection :<http://crash.ihug.co.nz/~awoodley/regency/army.html>

Prices of Officer’s Commissions Day, Malcom. (2006) Voices from the World of Jane.

Southam, Brian (2005). Jane Austen in Context. Janet M. Todd ed Cambridge University Press

Tomalin, Claire. (1999). Jane Austen, a Life. Random House

Watkins, Susan . (1990). Jane Austen’s Town and Country Style. Rizzoli

Thanks for this very useful explanation of the difference between the militia and the regular arny. I often wondered how George Wickham could afford to be an officer.

I had a nose around but couldn’t find the other article referenced here (“These men are members of the militia, not the regular army (discussed in the last post.)”)

Not sure if you still see comments here, but wondering if you could tell me if you think Col Fitzwilliam was in the regulars or Militia? If in the regulars, how was it that he had time for leisure to visit Mr Darcy and Lady Catherine? Trying to research this for a short story. Thank you!