Defining beauty in the Regency era

Nicolas Andry (1743) suggested that deformity, suggested that polite society should shun anything ‘shocking’, like visible impairments which might threaten virtuous interactions. Moreover, individuals who permitted, by their neglect, their bodies to become ‘ugly’ offended both society and God’s intentions. Thus, ‘orthopaedic’ intervention to restore the proper aesthetics to the body was an act of social and moral responsibility.

Causes and preventions of deformity

Experts concluded that preventing deformity was preferable (and easier) than curing it. Many suggested ignorant management in childhood was at the heart of many disfigurements and as such, more ‘scientific’ management might be applied to remedy them.

Towards the end of the Georgian era, malformations were classified by their causes including:

Those produced before birth

The result of tight lacing of long corsets, thought to impede the mother’s digestion, breathing, circulation and to even displace the womb itself. This practice was thought to impede the proper growth of a child resulting in dwarfism of other deformities of shape. Teaching mothers not to wear tight garments during pregnancy offered a simple remedy to this malady.

Those produced by ignorant nursing

In this case nursing referred to the care of the child in infancy. Infant bones were considered soft and unfinished, and the joints susceptible to injury by rough handling. Caregivers were directed to handle the infant as little as possible, allowing them to lie on mats and cushions without restrictions, and prevented from sitting and standing too soon.

Those produced by clothing in infancy

The practice of tight swaddling was still practiced in the Georgian era. However, toward the end of the period, the practice fell out of favor. The tight constriction of the infant was thought not only to be painful, but to restrict blood flow and to impede normal growth, forcing limbs and spine into unnatural shapes. Nurses were advised to adopt a looser mode of dress, but not so loose as to fail to support ‘feeble’ infant muscles, and to avoid dressing an infant to warmly and causing sweats in the night.

Those produced by dress in youth

Putting pressure on muscles was thought to weaken them. So the use of corsets, tight sleeves or garters was advised against and they might result in twisting the body out of natural position. Children’s clothing should be comfortable and allow the blood to flow freely and the body to move easily.

Those produced by position

Sleeping on the same side of the bed every night, sitting on the same side of the window or fire every night or in any way that twists the body was to be scrupulously avoided. While reading, writing, sewing or practicing music, young ladies must maintain perfectly erect posture to avoid permanent deformation of the spine.

Correcting deformity

Once deformity occurred, Sheldrake argued that the amelioration of such irregularities was imperative as ‘not only their appearance is disagreeable, but by impeding the function of viscera, they will in time destroy that balance of the constitution which is so necessary to health and longevity.”

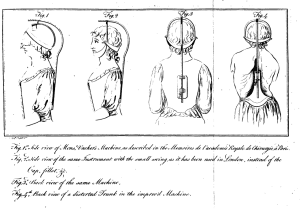

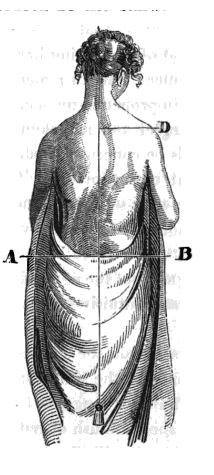

Stay makers and truss makers of the mid to late eighteenth century flooded the market with a cornucopia of devices to train young people’s bodies—particularly those of young women—as one trained young plants to grow strong and straight, often using braces and other contraptions made of newly available cast steel.

Braces and other devices

Devices to improve posture and keep and individual ‘straight’ were as varied as the manufacturers who made them. Large pieces of metal called backirons were hidden at the back of clothing and prevented slouching. Steel collars forced wearers to obey mothers’ and governesses’ injunctions to keep heads up, sometimes assisted by shoulder braces which pulled shoulders back. Neck swings stretched the spine by suspending the ‘patient’ in block and tackle type device so that only their toes touched the ground.

Education chairs which forced the ‘patient’ to balance in a small hard seat without a support to lean against while windlass contraptions and stretching chairs performed similarly to neck swing. Despite the discomfort and pain these devices caused, they were widely sold throughout the eighteenth century.

As the century drew to a close and the nineteenth century dawned, as shift of perspective occurred leaning toward a more natural beauty, unencumbered by the rigorous management and training of the previous generations. The second part of this article will examine these changing conceptions of beauty and how to achieve it in the Regency era.

Defining Beauty in the Regency

As the nineteenth century dawned popular views of beauty also shifted. Garments, particularly for women, changed from highly structured garments that relied on rigid undergarments to hold both the body and the garments in the desired shape, to flowing, easy gowns influences by classical designs of the ancient world. ‘Naturalness’ of the female form was highly prized, whether attained by natural means or not.

Move toward Naturalness

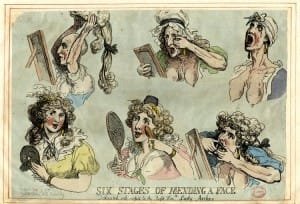

Perhaps related to political climate of the era, fears of artifice and the romanticism of the ‘natural’ state moved to the forefront of people’s minds. People feared duplicity, particularly that of women whose artful embellishments might lure unsuspecting men marriage without truly recognizing the condition of their bride. Artist Thomas Rowlandson satirized this fear in his print ‘Six Stages of Mending a Face’. While this may appear shallow to the modern mind, in the era, deficiencies of the body were often seen to correspond to deficiencies of moral character, a serious matter indeed.

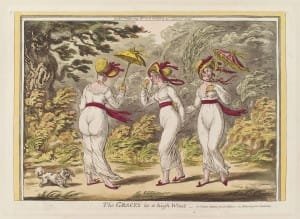

(Ancient) Greek influence, which was free of ‘unnatural straps’, braces and other ‘wicked inventions’, permeated period beauty ideals. The Book of Health and Beauty notes: “The Greeks, then, conceived that beauty was necessary to inspire love; but that the power of Venus was fleeting and transitory, unless she was attired and accompanied by the Graces, that is, unless ease and affability, gentleness and spirit, good humor, modesty, ingenuousness and candor engaged the admirers that beauty attracted.”

These ‘decent Graces “join hand in hand, to show that cheerfulness, vivacity, and youth, should be united with sincerity, candor, and decorum: and to assure the beholder, that unless he or she possess all these qualities he cannot boast of being a favorite with the Graces. They are in motion, because without motion there can be no grace. Their movements, you will see, are animated and soft; and the decided character of the whole group is a noble simplicity, and an unaffected modesty.” Thus, the ability to move and hold one’s body properly became an integral component in the definition of beauty.( The Book of Health and Beauty)

Movement and Posture

The Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion explains, “All grace consists in motion. The great secret of it is to marry two apparent contradictions,-—to unite, in the same movement, quickness and softness, vivacity and mildness, gentleness and spirit…The union of those two requisites is necessary in dancing, walking, bowing, talking, carving, presenting or receiving any thing, and, if we may venture to add, in smiling. Ease is the essence of grace: but all motions, quick and smooth, will necessarily be easy and free.”

Grace in all areas had to be entirely natural for any affectation would destroy the effect, as was often the case in stage performers. To be considered graceful every motion needed to be free from confusion or hurry while being lively and animated. Not only did all the motions of the legs, hands and arms need to be graceful, but the head, neck and even speech had to display grace as well. The epitome of grace in speech required the unity of vivacity with softness in the voice and simplicity of speech. Needless to say, the development of grace required practice, so lessons in deportment began early.

Ladies began such practice in childhood as they learned to move properly in the long skirts fashion and decorum required. Small steps that pushed skirts out of the way allowed a young lady to appear to glide as she moved. Steps would be made from the knee, rather the hips, as swaying the hips as one walked was indecorous. Turns were made with the whole body allowing garments to turn elegantly and gracefully. When sitting, ladies kept their knees spread, rather than crossing their legs, in order to keep their skirts neat. Arms kept gracefully at ones side, emphasizing the long elegant column of their classically inspired, empire-waist gowns. If they had to cross their arms, it was done at the high waist line, so as not to spoil the line of their gowns.

Grace was expected, even required of men as well as women. Unlike women, they were not taught deportment, however, training in fencing sufficed for the purpose. Not only did fencing give men well shaped legs—which were shown off constantly in skin tight pantaloons and breeches—it trained them in balance, graceful movement. The same effortless, elegant motions that carried them through a fencing bout were equally welcome on the dance floor.

Above all, perfectly erect and graceful posture was essential. Sitting, standing, walking or dancing, the spine was held straight and the head perfectly balanced atop a supple neck. To slouch was to risk deformity of the spine and to demonstrate disrespect and weakness of character.

For men, imperfect posture also risked chaffing and irritation from their fashionable garments. The cut of their coats, with armholes cut mostly in the back of the garment, rather than evenly distributed front to back as they are in modern garments, pulled shoulders back and opened the chest. High, stiff coat collars that often came up to their ears would irritate the back of the neck and even ears, if the spine was not straight and head held high, while a drooping chin could crush and soil a carefully tied cravat.

For all that ‘natural’ beauty was emphasized, ladies and gentlemen worked very hard Clcto attain the standard of beauty. For those whose natural state was farther form the ideal, recommendations abounded upon how to improve on what nature graced on with. The next part of this series will look a how one might improve upon nature’s gifts.

Comments

Defining beauty in the Regency era — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>