Properties of Granite

Granite is one of the most well-known and widely used stones on Earth and has been for millennia. Today we see it in kitchen countertops, on the face of buildings, and in shrines, mausoleums and gravestones. Many ancient monuments were built with granite, including some Egyptian pyramids and obelisks, the Roman Pantheon, and the Thanjavur Big Temple and Brihadeeswarar Temple of India. In the Middle Ages, granite was a key material for building castles and churches because it could withstand the elements for centuries. So it isn’t surprising to find my World Wrights using granite in their endeavours.

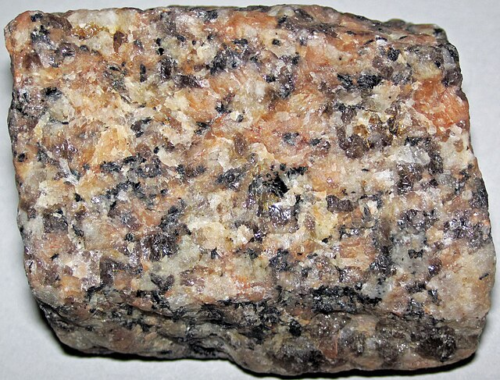

What Is Granite?

Granite is an igneous rock, formed by slow cooling molten rock (magma) deep beneath the Earth’s crust. This gradual cooling process allows large crystals to grow, giving granite its distinct speckled appearance.

Granite is primarily made up of three minerals:

- Quartz: typically the clear or white component

- Feldspar a pink, white, or gray, and sometimes even green component

- Mica appearing as tiny, shiny black flakes

Together, these minerals make granite incredibly strong and durable, which is why it has been used for thousands of years in construction. They also give granite surprising piezoelectric properties.

What Does Piezoelectric Mean?

The word piezoelectric comes from the Greek “piezo” which means “to squeeze” or “to press,” Piezoelectricity is a property that allows certain materials to generate an electric charge when they are subjected to mechanical stress, like squeezing, stretching, or vibrating.

A classic example of a piezoelectric material is quartz. If you apply pressure to a piece of quartz, it produces a small electric charge. This effect is used in everyday technology, like quartz watches, which rely on vibrations in a quartz crystal to keep time accurately.

Since granite contains quartz, it also exhibits piezoelectric properties. However, the effect in granite is more complex because it is a mix of different minerals. When granite is stressed—by natural forces like earthquakes, underground pressure, or even human activity—it can generate weak electrical signals.

This also explains the ‘bite’ David Enright complains about while working with granite. in Wrighting Old Wrongs.

Rebecca teaches him how to push heat into the granite to alleviate it’s ‘bite’. Her technique works because piezoelectric materials are affected by heat. Their ability to create electricity degrades significantly when exposed to high temperatures. So heating the rock as they work it prevents the unpleasant, distracting shocks Wrights struggle with when manipulating granite.

Thank you for your piece on Granite. I enjoy Geology (did it for A Level). Granite is one of my favourite rocks and I chose a really pink variety to be made into the book-shaped headstone for my first husband’s grave.

I was surprised to learn that the wrights working with granite were based on real-world facts. I shouldn’t have been surprised because I’ve seen the depth of your research in your other books, but I didn’t expect you to build real-world science into such a magical ability.