Taxed, smuggled and adulterated: Tea in Britain

“Polly put the kettle on, we’ll all have tea.”~Charles Dickens (1812-1870) Barnaby Rudge

Since its popular introduction by Catherine of Braganza, in 1662, tea in Britain was an expensive commodity

It was so expensive it was usually kept under lock and key, protected from pilfering by the servants. Both the cupboards and the tea caddies were locked and the key kept by the mistress of the household.

Two primary types of tea were available, green and black. Black teas included bohea, souchong, congo (or congou) and pekoe, bohea being the cheapest, pekoe the most expensive. Of the green teas, singlo was the cheapest. Other varieties included hyson, caper, and bloom. Different types of tea leaves would be combined to produce tasty blends for consumers.

Both forms of tea began with the same leaves, but they were processed differently. Green tea leaves were roasted as soon as they are gathered to prevent fermentation. Black tea leaves were allowed to ferment for some time. The brown/black color and flavor developed during fermentation. Roasting stopped the process.

The tea trade recognized nine different grades of quality in both green and brown/black teas. The cheapest might be found for 5-6 shillings per pound. The best grades could cost as much as 20 shillings or more a pound. In 1800 a year’s supply of tea and sugar could cost a family of six nearly as much as their yearly rent. (Of course the anti-slavery movement discouraged the use of sugar…)

Why was tea so expensive?

Two major factors contributed to the cost of tea: cost of import and taxes.

In the Regency era, tea had not yet been cultivated in India, so all supplies had to be shipped in from China. The journey from China to Britain could take more than a year to complete. In China, foreign traders were confined to trading in Canton. Trade was strictly regulated by Chinese officials with only the Hong guild licensed to deal with foreign traders. These merchants were taxed heavily by their own officials and in turn passed their expenses off to the traders, thus increasing the cost of exported goods.

Once the tea entered Britain, the local government would add their own taxes which further increased the cost. In 1784, dry leaf tea was taxed at a shilling a pound. By 1801, tax rates increased to 2 shillings, 6 pence a pound.

Smuggling

Richard Twinning, of Twinning Tea company, estimated at least half of the tea drunk in England was smuggled. Even in 1820, tea was one of the two most smuggled commodities, the other being liquor.

Smuggled tea often came from Holland where it might be purchased for as little as 7 pence per pound. This tea was then transported to England by ship and sold at 2 shillings a pound, a third of what legally procured teas sold for.

The smugglers, who often were local fishermen, snuck the tea from offshore ships to smaller vessels which brought it to land in oilskin bags. On land, the tea was repacked in sacks to minimize the taste from the oilskin and taken by horse to various hiding places. (Even so, smuggled tea was known for the ‘off’ taste imparted by the oilskin.) Parish churches often were used to stash the ill-gotten goods.

To make the smuggled tea even more lucrative, many smugglers adulterated the tea with other substances, until the Food and Drug Act of 1875 brought in stiff penalties for the practice.

Adulterated tea

Prepacked tea was not produced until 1826 making it very susceptible to contamination. Moreover, tea was never sold in outdoor public markets, but in smaller shops, like chandler’s shops, further increasing its vulnerability. Loose tea, sometimes called gunpowder was more difficult to successfully adulterate and was thus more expensive than dried and ground versions.

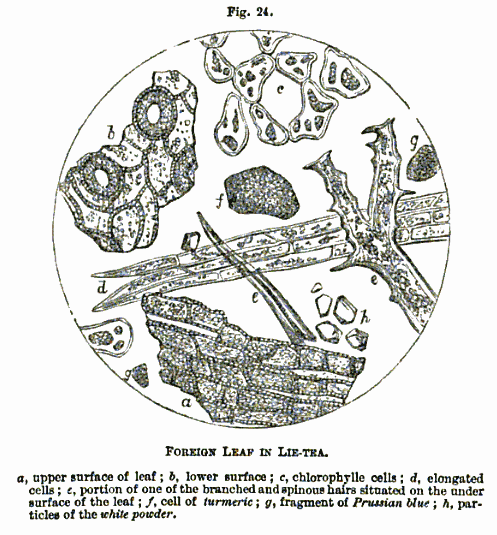

Green teas were generally thought easier to adulterate, so public preference shifted to black tea. Not to be outdone by wary consumers, unscrupulous merchants stretched black tea supplies with both used tea leaves, colorants and other contaminants.

Used teas leaves were in ready supply. In wealthy households, it passed through the household hierarchy. First the family brewed and drank of it. Then the used leaves would the given to the servants to brew and drink. Finally, they would end in the hands of a high ranking servant, cook or housekeeper, who, as part of her contract would be entitled to the used leaves. She would then dry and sell them to a char woman or directly to poorer families for as much as a shilling a pound.

Char women might resell the used leaves to a slop shop who would then process them for reuse. The leaves were stiffened with a solution of gum, colored with green vitriol (iron sulfate) or black lead and combined with fresh tea leaves. Willow, licorice, log wood and sloe leaves might also be added to further extend the mixture. No doubt it tasted little like real tea, but it did contain actual tea leaves.

Fake tea called ‘smouch’ or sometimes ‘British tea’, which did not, was also widely available. Counterfeit green tea could be produced from thorn or ash leaves, steeped in green vitriol or verdigris (copper acetate) and dried. These dyes were toxic and could produce a variety of symptoms including constipation.

Imitation black tea often contained the same hawthorn, ash and sloe leaves. It might also be a mixture of bran and animal dung or ‘chamber lye’ (the contents of a chamber pot). Dried and ground these were said to strongly resemble fashionable bohea tea in appearance if not in flavor. (I shudder to think what this must have tasted like…)

Some estimates suggested up to three million pounds (weight) of these mixtures were produced a year. So while most of the nation drank ‘tea’, the contents of many tea cups might not have been as pleasant as the drinker might have wished.

Ironically, even these adulterated teas would have provided the working class with the safest way of taking in water (boiled to make the tea) because of the water supply was often more contaminated than the tea.

Resources

http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelpregion/asia/china/guidesources/chinatrade/index.html

http://www.britainexpress.com/History/tea-in-britain.htm

Fullerton, Susannah and Hill, Reginald. Jane Austen & Crime. Jones Books. (2006)

Horn, Pamela. Flunkeys and Scullions, Life Below Stairs in Georgian England . Sutton Publishing (2004)

Murray, Venetia. An Elegant Madness Penguin Books (1998)

Olsen, Kirstin. Cooking with Jane Austen Greenwood Press (2005)

Wilson, Kim. Tea with Jane Austen Jones Books (2004)

Oh dear, another reason for not living in those times (in fact I think Darcy would be the only reason I would want to live then so the solution would be for him to live now – with me!!!!!)

I write this as I am enjoying my second cup of tea today ???

Thanks so much for this post Maria, I do so love all the research you authors do in writing your wonderful books.

Thanks so much! It was pretty interesting research to do.

Oh dear! And I thought myself to be such a sophisticated lady when I drank Earl Grey or English Breakfast Tea! What of the many teas I the samplers I bought for my grandmother every Christmas? Well, she did live to be 95 …. !;

Hmmm, there could be something to that.

Yuck!!!! Ew!!!! Ick!!!!

Although part of me wishes to live in the 19th century, this tale of tea makes me very glad for Trader Joe’s Irish Breakfast sipped from my Tardis mug. 😉

Warmly,

Susanne 🙂

I had the same thought when researching this!

‘Contents of a chamber pot’!!!!! Good lord I’m glad I don’t drink tea anymore. That’s enough to put anyone off. Well I do drink tea but only nettle tea. I had to give up dairy about three years ago as I developed an intolerance to it. I just could not stomach the tea without milk or with any of the alternatives. I really like the nettle tea now. It’s refreshing and is just as nice drunk cold as hot. Lovely post.

I found that part really unsettling too! My favorite is hibiscus tea–steeps an amazing color!

Pingback:Making Drinking Chocolate the Regency Way - Random Bits of Fascination