A Touch of Consumption

I’d like to welcome Kyra Kramer today as she shares a fascinating article on consumption–known today as tuberculosis–during the regency era.

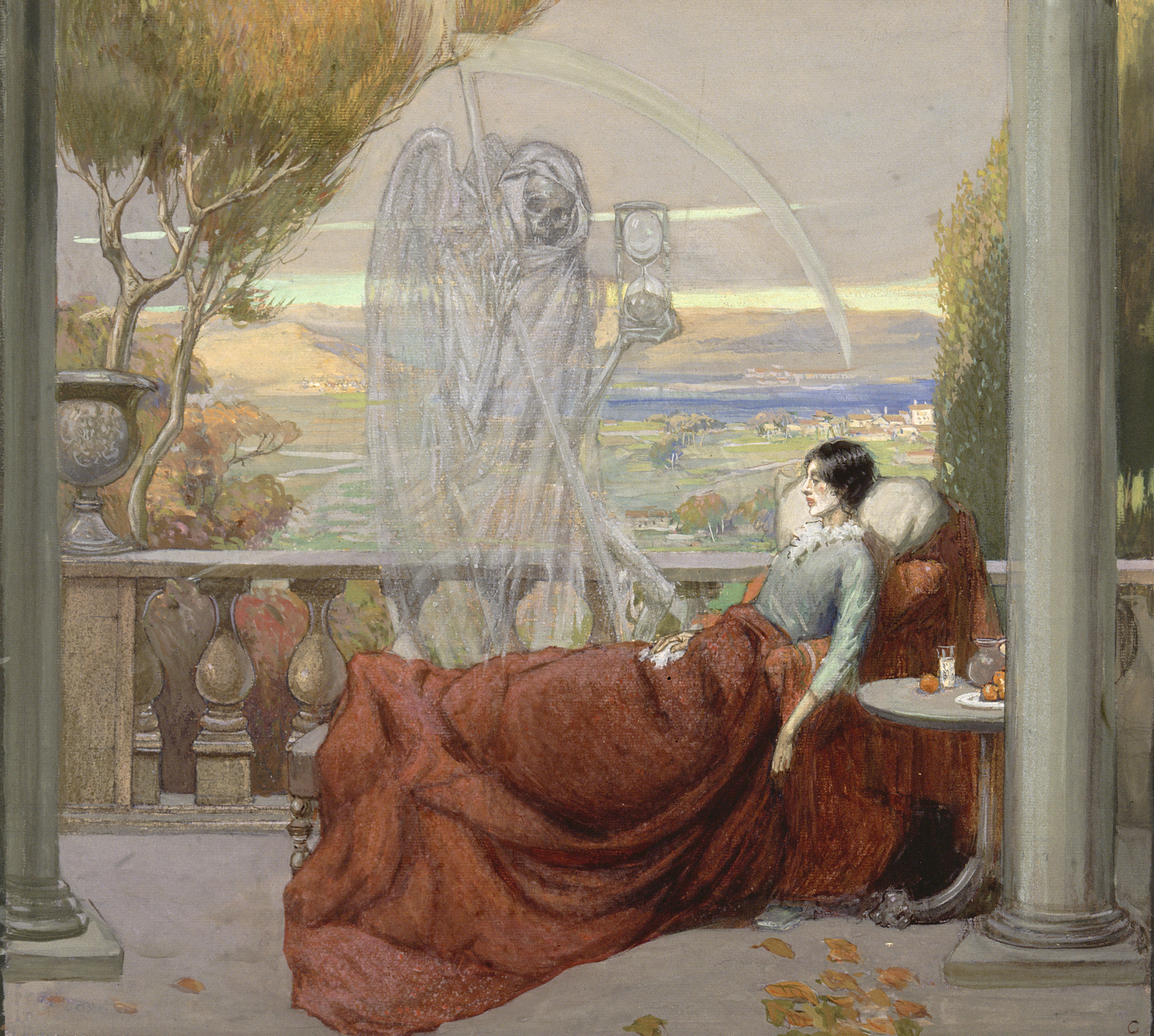

Watercolour by Richard Tennant Cooper

Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Medical anthropology is the study of how culture frames health, illness, and medicine. Since cultures change over time, you can also look at medical anthropology from a historical perspective. For example, the way British people during the Regency era conceptualized consumption – AKA tuberculosis – was very different from the way people in the UK understand of it now. While most modern Westerners don’t really have to think about TB much nowadays, in the early 19th century it was both an incurable, pandemic scourge … and strangely sexy.

What? Coughing until bits of lung tissue come up and you die of asphyxiation was sexy?

No, not that part of TB. The sexy bit was the pallid skin, frailty, burning cheeks, lustrous eyes, and long periods of lying in bed with loved ones weeping over you that often came with dying of consumption.

The epitome of Regency poets, Lord Byron, said he wanted to die of consumption because it would make him seem very interesting to the ladies. He was not alone in this wish. Consumption was the darling of the Romantic Movement, and was seen as the acme of the ‘good death’. Preferably the consumptive would be a sensitive yet brave young man, wasting away as if feeding a fiery passion in his soul, or if the sufferer were a woman, then she should be the wan and pure object of devotion for a tender lover devastated by her loss. Everyone wanted to get in on this act. Gentlemen would try to effect an underfed moodiness, while ladies would try to look as delicate and languid as possible. Both genders would attempt to appear resigned to their inexorable fate, above such earthly concerns as breathing. It was all very tragic and wonderful, especially if you got to live a long full life enjoying your putative decline. The only thing that could possibly top death by consumption was to die of a broken heart.

How on earth did tuberculosis, a disease that afflicted the poor and working class more often than the well-to-do and upper class, become such a cool and interesting way to die? Well, first you must understand that the consumption of the Romantics wasn’t quite the same as the nasty White Plague and scrofula that killed almost 1/7th of Britons during the Regency era. That disease, which was gross, was probably caused by moral failure and criminality. Consumption among the genteel, while actually identical to the tuberculosis sweeping through crowded slums and prisons, bore no sociocultural relationship to the icky stuff impoverished people got. Tuberculosis in the upper crust was cause by too much emotion and genius.

In the days before germ theory, which wouldn’t come about until the Victorians a generation or two later, no one really knew how TB was transmitted. Doctors, who still embraced humoral medicine at the time, assumed that the illness came about when the passions of the melancholy person overwhelmed them and destroyed their health on the altar of mental acuity. As with the modern mind, bias effect came into play; people in the Regency noticed when famous artists they admired died of consumption just like we notice when rock stars die at age 27. The consumptive deaths of famous poets and composers, who were clearly in procession of a surfeit of feeling and brains, linked the idea of TB with artistic temperaments in the popular imagination. To have consumption was to demonstrate you had both profundity and intellect.

Moreover, producers of popular art and literature were prone to put characters in their work who died of consumption because of their deep and uncontrollable emotions. To die of consumption showed you were a person of genuine quality. It was something akin to being a princess who slept on a pea; TB revealed you as the kind of top-notch individual who was so refined you could detect a legume through 20 feathered mattresses. Even better, if the female character had sinned (particularly in a sexual manner), then dying of TB explained that her sins were based on the excess of love rather than wanton indulgence. Consumption redeemed her, and made her mourn-worthy. Remember Eliza, the early love of Colonel Brandon in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility? She was thwarted in love, pressured into marriage, had an affair, got a divorce, gave birth to a child outside of wedlock, and was either reduced to prostitution or one step above it. Nonetheless, by dying in a sponging house of TB, Eliza ‘proved’ that her errors were all the fault of being unable to marry Colonel Brandon as a young woman. Established as having an overly-affectionate heart unable to survive her disappointments, she was therefore an ethereal, fervid beauty comparable to Marianne Dashwood rather than a mere ‘fallen woman’.

Then there was the fact that TB was considered a “beautiful” death … by people who had clearly never seen it in action. What is considered beautiful in humans varies from culture to culture, but it ALWAYS reflects wealth and power. If the penurious are prone to overweight puffiness, then the beautiful are contrastingly thin and well-toned. If the disenfranchised are darkly complexioned, then the beautiful are pale.

In the early 19th century those who labored, and were hence the socioeconomically marginalized, were typically muscular/robust and tanned. In response, the ideal became very pale and slender. Even athletic and hale military officers were supposed to be thinner than the rabble who fought in the field. Gentlemen without professions were thought most attractive when they were lithe. That’s why skin-tight buff breeches and buttoned coats were so fashionable for men of the Beau Monde; the styles were designed to show off a lack of adipose tissue on the thighs, buttocks, and belly. As for women, they needed to be as willowy as possible (albeit not as thin as the 1990s heroin chic model) and preferably the color of alabaster. As with men, fashion highlighted this with ‘classical’ dresses that would flow and drape around a woman’s small waist and display her exquisitely undefined arms. However, since women lost value as they aged, they were supposed to be youthfully rosy-cheeked as well as bloodless. There was also, for both genders, a preference for “fine eyes” that were bright and positively sparkling, in contrast to the weary, nutrition-deprived, dullness of eyes in the lower classes.

This image of Regency beauty was the very model of the privileged consumptive. The loss of blood and appetite rendered a consumptive pasty and emaciated, while sufficient caloric intake produced a feverish flush that would give the patient a faux bloom on their cheeks and a ‘brilliant’ eye. This elided the wracking cough, night sweats, glandular ulcers, sputum, and agonizing end of tuberculosis, but physical reality has never been able to deter the cultural construction of a disease as an impressive way to die. Consumption became an impressive way to shuffle off one’s mortal coil because of its fictional connection with attractiveness and talent. Likewise, modern social beliefs are why movie and rock stars die ‘tragically’ of drug overdoses and develop cult followings, but homeless addicts are just dead junkies. The fact that they all asphyxiated on their own vomit the same manner matters less than the fact several good-looking, well-known people died that way. Times change, norms change, fashions change … but humans remain the same.

Sources:

Bordo, Susan. 1993. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley: U of California.

Bryder, Linda. 1988. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bynum, Helen. 2012. Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lawlor, Clark. 2006. Consumption and Literature: The Making of the Romantic Disease. New York, NY: Pelgrave Macmillan.

Sontag, Susan. 2001. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York, NY: Picador.

Wilsey, Ashley M. 2012. “Half in Love with Easeful Death: Tuberculosis in Literature.” Pacific University Common Knowledge. Humanities Capstone Projects. Paper 11.

Kyra Kramer is a medical anthropologist, historian, and devoted bibliophile who lives just outside Cardiff, Wales with her handsome husband and three wonderful young daughters. She has a deep — nearly obsessive — love for Regency Period romances in general and Jane Austen’s work in particular. Ms. Kramer has authored several history books and academic essays, but this is her first foray into fictional writing. You can visit her website at kyrackramer.com to learn more about her life and work.

About her latest book: Mansfield Parsonage:

Fans of Jane Austen will recognize the players and the setting–Mansfield Park has been telling the story of Fanny Price and her happily ever after for more than 200 years. But behind the scenes of Mansfield Park, there’s another story to be told. Mary Crawford’s story.

When her widowed uncle made her home untenable, Mary made the best of things by going to live with her elder sister, Mrs. Grant, in a parson’s house the country. Mansfield Parsonage was more than Mary had expected and better than she could have hoped. Gregarious and personable, Mary also embraced the inhabitants of the nearby Mansfield Park, watching the ladies set their caps for her dashing brother, Henry Crawford, and developing an attachment to Edmund Bertram and a profound affection for his cousin, Fanny Price.

Mansfield Parsonage retells the story of Mansfield Park from the perspective of Mary Crawford’s hopes and aspirations, and show’s how Fanny Price’s happily-ever-after came at Mary’s expense.

Or did it?

Books by this author:

Using these affiliate links supports this website!

I have Mansfield Parsonage on my TBR pile as Mansfield Park is one of my favorite Austen novels. That was a great post. Very interesting.

Thanks, Teresa!

Thanks for a fascinating, if somewhat morbid, post. Puts a whole new spin on the phrase “pale and interesting”.

IT does, doesn’t it?