A Tale of Two Weddings, pt 1

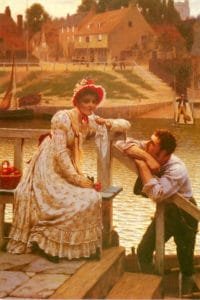

Throughout the 19th century, from the Regency period to the height of the Victorian era, marriage stood as a foremost social and economic institution in England. Far more than a simple union between two individuals, (that would be too simple now, wouldn’t it?) it was a strategic alliance that defined futures, consolidated wealth, and cemented social standing. So it’s no surprise that the rituals surrounding weddings were powerful and nuanced performances of class identity, economic capacity, and social aspiration.

The legal pathways to the altar, the nature of courtship, the grandeur (or lack thereof) of the ceremony varied dramatically across the social landscape. If it all sounds complicated, imagine what happens with dragons and World Wrights get involved!

The Legal Foundations of Marriage: A System of Class Distinction

Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753 standardized the legal requirements for marriage, effectively ending clandestine ceremonies. This all-important social act needed to have proper record-keeping and recognition attached to it.

The Hardwicke Act also created a tiered system of legal entry into matrimony, whereby the choice of method served as an immediate and clear marker of a couple’s social class.

Marriage by Banns: This was the most common, public, and free method, making it the default for the “humbler classes.” The process involved the parish clergyman publicly announcing the couple’s intention to marry on three consecutive Sundays, a form of community surveillance that invited anyone to voice a “cause or just impediment.” Usual impediments were consanguinity (being too closely related) or already being married. While ensuring transparency, this method sacrificed the privacy that wealth could afford.

(It interesting to note just how much privacy was considered a luxury of the wealthy, that that’s likely to be a future rabbit hole.)

Common License: For those who wished to avoid the public scrutiny or delay of the banns, a common license offered a respectable alternative. Positioned as a middle-class compromise, it could be obtained from a bishop for a fee that rose from around 10 shillings to two or three pounds over the century. This license reduced the waiting period to seven days, and required the couple to marry in the parish church where one of them had resided for at least four weeks. Its cost acted as a modest gatekeeping mechanism, separating those with some means from the general populace-which of course, is entirely necessary to preerve social order, right?

Special License: The pinnacle of marital exclusivity was the special license, a privilege reserved for the highest echelons of society. Available only from the Archbishop of Canterbury, these licenses were granted to peers, their children, baronets, knights, Members of Parliament, and other high-ranking officials. At a considerable expense of at least 20 guineas (a pound plus a shilling) plus a stamp duty imposed in 1808 at £4 that rose to £5 by 1815, it was a prohibitive cost for all but the elite. The extreme rarity of these licenses—with only six issued in 1730 and twenty-two in 1830—underscores their function as a marker of privilege that granted the holder the unique right to marry at any convenient time and in any location.

This stratified system set the stage for the social rituals that preceded the ceremony, beginning with the carefully managed process of courtship.

Courtship and Engagement: The Pathways to the Altar

Nineteenth-century courtship was a carefully managed social process, far removed from modern notions of romantic spontaneity. Its primary function was to ensure suitable matches that upheld class lines, preserved reputations, and secured sound economic futures. Sounds very draconic, doesn’t it?

Aristocratic Courtship: Focus on Fortunes

For the aristocracy, matches were made within a highly selective pool of peers. The London Season served as the primary matrimonial marketplace, where young men and women were introduced at balls and parties under the unblinking eyes of chaperones.

Once a suitable match was identified, engagements were often short, dominated not by romance but by financial negotiations. These dialogs, formalized in legally binding contracts, turned marriage into an economic merger. They included:

Dowries: A sum brought by the bride to the marriage. The 5th Duke of Devonshire, for example, bestowed an enormous dowry of £30,000 upon his eldest legitimate daughter.

Marriage Settlements: These contracts specified provisions for the wife, securing her financial future in the event of her husband’s death.

Pin Money: An annual allowance provided by the husband to his wife for her personal use, such as the £400 per year stipulated in Lady Caroline Ponsonby’s marriage agreement.

Engagement rings were not standard during the Regency. It was only in the Victorian era, following Prince Albert’s gift of a serpent ring to Queen Victoria and the increased availability of diamonds, that the diamond ring became a fashionable symbol of betrothal among the wealthy.

Middle-Class Courtship: Focus on Prospects

The rising middle class emulated the formal, chaperoned courtships of the aristocracy but adapted them to their own values. Young people met the sons and daughters of family friends in controlled settings, with parental guidance emphasizing a partner with “good prospects” and shared religious values to ensure a respectable and stable union.

Working-Class Courtship: Freedom and Frugality

In sharp contrast, working-class couples experienced greater freedom from direct parental supervision, having often left home at a young age to work in factories or shops. Their engagements were typically longer, not by choice but by necessity, as they needed time to save the funds required to establish a home. Once these practicalities were addressed, the couple could proceed to the wedding ceremony.

Stay tuned for the next installment when we’ll talk abut all the wedding details!

Read more about Regency era Courtship and Marriage

References

Knowles, Rachel. “Hardwicke’s Marriage Act and Wedding Licences.” Regency History. https://www.regencyhistory.net/blog/marriage-licences-banns-regency-history-guide (accessed January 26, 2026).

“Unveiling Victorian Wedding Traditions.” MASTERPIECE, PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/specialfeatures/unveiling-victorian-wedding-traditions. (accessed January 26, 2026).

“Regency Wedding Breakfast.” Jane Austen History. https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/regency-history/the-regency-wedding-breakfast (accessed January 26, 2026).

BBC/Wikipedia, Wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wedding_of_Queen_Victoria_and_Prince_Albert (accessed January 26, 2026).

Betts, Charlotte. Courtship and Weddings in the Victorian Era. Charlotte Betts. https://www.charlottebetts.com/courtship-and-weddings-women-and-marriage-in-the-victorian-and-edwardian-eras-part-1/ (accessed January 26, 2026).

Bolen, Cheryl. “Courting and Marriage in the Regency.” Cheryl Bolen, Author. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.cherylbolen.com/courting.htm . (accessed January 26, 2026).

Boyle, Laura. “The Regency Wedding Breakfast.” JaneAusten.co.uk, April 19, 2016. https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/jane-austen-life/the-regency-wedding-breakfast (accessed January 26, 2026).

Boyle, Laura. “Weddings During the Regency Era.” JaneAusten.co.uk, June 20, 2011. https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/jane-austen-life/weddings-during-the-regency-era (accessed January 26, 2026).

Cox, Brenda S. “Banns, Common Licenses, and Special Licenses: Permission to Marry in Jane Austen’s England.” Jane Austen’s World (August 23, 2021). https://janeaustensworld.com/2021/08/23/banns-common-licenses-and-special-licenses-permission-to-marry-in-jane-austens-england/ (accessed January 26, 2026).

Eastwood, Gail. “What We ‘Know’ about Regency Weddings.” Risky Regencies, September 10, 2020. https://riskyregencies.com/2020/09/10/what-we-know-about-regency-weddings (accessed January 26, 2026).

Ives, Susanna. “Victorian Wedding Etiquette.” Susanna Ives | My Floating World, November 14, 2015. https://susannaives.com/2015/11/14/victorian-wedding-etiquette (accessed January 26, 2026).

Knowles, Rachel. “Banns, licences and Hardwicke’s Marriage Act – a Regency History guide to marriage in Georgian England.” Regency History, October 17, 2021. https://www.regencyhistory.net/2021/10/banns-licences-and-hardwickes.html (accessed January 26, 2026).

Koster, Kristen. “A Regency Marriage Primer.” Kristen Koster, Author, October 11, 2011. https://kristenkoster.com/a-regency-marriage-primer. (accessed January 26, 2026).

PBS. Unveiling Victorian Wedding Traditions. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/specialfeatures/unveiling-victorian-wedding-traditions/ (accessed January 26, 2026).

Wikipedia, Wedding Dress of Queen Victoria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wedding_dress_of_Queen_Victoria (accessed January 26,2026).

Comments

A Tale of Two Weddings, pt 1 — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>