Money Lending in the Victorian Era: From Prohibition to Predation

In Wrighting Old Wrongs, Rebecca’s most immediate problem is the debt her late father owed a particularly despicable money lender, a dilemma faced by many in the Victorian Era. What made debt and moneylenders so insidious?

For centuries, moneylending was viewed with suspicion, if not outright hostility. Across the Abrahamic faiths, usury (charging interest was considered sinful. The Catholic Church, Islamic jurisprudence, and Jewish communal laws all condemned lending for profit as exploitation of the vulnerable, a system that entrapped the poor in lifelong debts without hope of escape. The very word “mortgage” derived from the French mort gage—a “death pledge”—suggesting that debt was as final as the grave. How’s that for telling a story in a single word?

During the Victorian period, centuries of moral censure gave way to an almost celebratory embrace of lending-for-profit as an engine of modern finance. The shift began much earlier, though, during the Renaissance, with Italian banking innovations like the bill of exchange, which skirted prohibitions by disguising loans as currency transactions.

John Calvin’s acceptance of low-interest lending in the 16th century broke the religious taboo for much of Protestant Europe, laying the foundation for institutions such as the Swiss banks. By 1845, the English Parliament had swept away the last restrictions on usury. Money lenders could now charge borrowers whatever they wanted. And with so many poor people in the cities—thanks to the Enclosure Acts and a shift from farming to factory work—there were plenty of people desperate enough to take those loans. Money lending was no longer an illicit act but a fully legal and immensely profitable business.

The New World of Victorian Lending

Once the prohibition fell, a diverse web of lending options multiplied across Britain. Ranging from from the humble to the grand, together they ensnared borrowers at every social level.

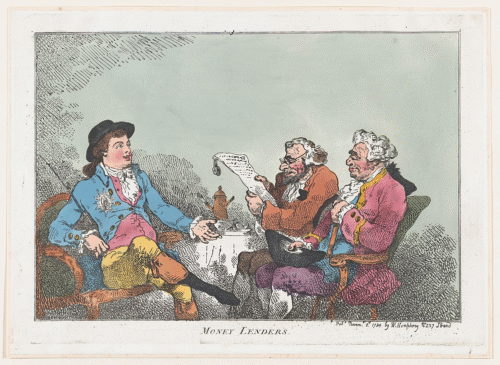

Who were these dangerous predators? (A little dramatic, yes, but considering the reality of the situation, it’s not inappropriate.)

Pawnbrokers, the most visible lenders, operated at the street level. Nearly as common as public houses, their shops displayed the traditional sign of three golden balls (a symbol of St Nicholas who, legend says, saved three young girls from destitution by loaning them each a bag of gold so they could marry). They took items like bed linen, cutlery, or wedding rings as collateral for short-term loans, returning them if repayment with interest was made in time. Their rates, though regulated by Parliament through the Pawnbrokers Acts of 1800 and 1872, still burdened the poor. Their widespread prevalence was a necessity in a society where workhouse terror drove the poor to pawn their last possessions. (Johnson)

Financiers of the fashionable districts marked the other end of the spectrum. These men cultivated luxurious offices and social respectability, preying on young heirs or noblemen with mortgaged estates. They often began by discounting bills for clients. When defaults came due, they extended “accommodations,” sometimes in the form of speculative shares, that further entangled their victims. The ruined heir or embarrassed aristocrat found his inheritance mortgaged “up to the hilt,” often sold off at “ruinous sacrifice” (Williams).

“Banks of Deposit” money lenders occupied the middle ground between these two. These storefront operations in busy urban centers advertised loans “on the easiest terms.” In reality, they charged effective interest rates exceeding 100 percent. They added fees for preliminary inquiries, hired “needy solicitors” to ensnare clients, and employed a particularly vicious tactic: inducing borrowers to sign false statutory declarations. Once entrapped, the borrower could be blackmailed with threats of criminal prosecution unless wealthy relatives paid the debt. This was the sort of moneylender that Rebecca’s father had fallen prey to. (Williams).

Some lenders, sometimes called “Leviathan” lenders, like Leopold Sampson, operated openly at an enormous scale, embracing their trade, with some of the largest estates in the country passing into their hands. (Williams)

Borrowers in the Spider’s Web

For borrowers, this environment was treacherous at best. High interest rates, compounded by fees and legal traps, created what we would now call ‘debt spirals.’ For the middle classes, default meant the loss of all worldly goods under a bill of sale. For the wealthy, it meant disgrace and the loss of family estates.

For the working poor, pawning their last possessions was often the only way to avoid the workhouse, an institution reformed by the 1834 Poor Law to be deliberately harsh, “expensive, burdensome, and stigmatizing” (Tomkins, 2019) because, in the Victorian mindset, debt and poverty, were not merely a financial burden but a moral and existential threat to society.

The Victorian Workhouse

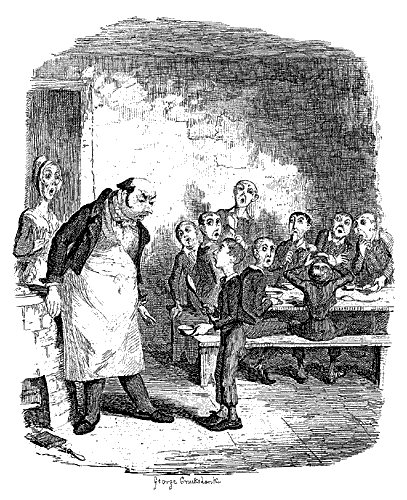

A Victorian workhouse was not just a building—it was a social institution deliberately designed to deter those seeking poverty relief by making the conditions so harsh that only the most desperate would submit to them. They were the backbone of Britain’s New Poor Law of 1834, which tried to cut welfare costs by centralizing poor relief and discouraging dependence on parish charity.

The guiding philosophy was “less eligibility”—meaning workhouses were designed to be less desirable than the worst form of independent labor. The aim wasn’t to alleviate poverty but to punish and reform the poor into self-reliance. (Since of course, as we all know, poverty was the result of bad morals and bad choices.)

Workhouses regulated every aspect of inmates’ lives. Families were split up—men, women, children, and the elderly were housed separately to prevent comfort or solidarity. Inmates wore coarse uniforms, ate standardized basic meals (bread, gruel, cheese, occasionally meat). Lodgings were bare, and medical care was minimal. Silence and obedience were strictly enforced. Inmates were subjected to strict routines of work, prayer, and discipline. Work was often deliberately monotonous and physically punishing, such as breaking stones, oakum picking (teasing apart tarred rope fibers with bare hands), or crushing bones for fertilizer. More punishment than productive employment.

Children were sometimes apprenticed out or educated within the institution, though the quality of this education was inconsistent and often exploitative.

The system reduced the cost of poor relief compared to the old parish-based outdoor relief. Local ratepayers (landowners and the middle class) were the main beneficiaries, as their taxes fell. But, by humane standards, workhouses were a dismal failure. Conditions were degrading, mortality rates were high (especially in the early years), and families were traumatized by separation. Many preferred starvation, emigration, or crime over entry. Who could blame them?

Against this backdrop, with no family to support her and a workhouse the only public support Rebecca could ever hope for, no wonder she had a mortal dread of debt and losses her father’s deals with the money-lender might cause her.

References

Becker, Jennifer Tate, “Round the Corner: Pawnbroking in the Victorian Novel” (2014). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1286. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1286 Accessed July 23, 2025. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/etd/article/2286/&path_info=Becker_wustl_0252D_11429.pdf

Brain, Jessica. “The Victorian Workhouse.” Historic UK. August 8, 2019. Accessed September 11, 2025. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Victorian-Workhouse/ Historic UK

Johnson, Ben. “The Pawnbroker.” Historic UK. Accessed July 23, 2025 https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Pawnbroker/

Tomkins, Alannah. “Why Universal Credit is like the Victorian workhouse.” Keele University, January 16, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2025 https://www.keele.ac.uk/about/news/2019/january/universal-credit/hardship.php

Williams, Montagu. “Money Lent.” Chap. 12 in Round London: Down East and Up West. 1894. Presented on Victorian London. Accessed July 23, 2025 https://www.victorianlondon.org/publications/roundlondon2-12.htm

Willliams, Samantha. “Poverty, Gender, and Old Age in the Victorian and Edwardian Workhouse.” Brewminate. December 11, 2024. Accessed September 11, 2025. https://brewminate.com/poverty-gender-and-old-age-in-the-victorian-and-edwardian-workhouse/

Yokoyama, Keiko. “A Christmas Carol and the Rise of the Debt Society in the 21st Century.” Resilience.org, January 14, 2021. Accessed July 23, 2025 https://www.resilience.org/stories/2021-01-14/a-christmas-carol-and-the-rise-of-the-debt-society-in-the-21st-century/

Comments

Money Lending in the Victorian Era: From Prohibition to Predation — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>