The History of Circulating Libraries

In honor of National Library Week, I’m reposting this series on the libraries of Austen’s day.

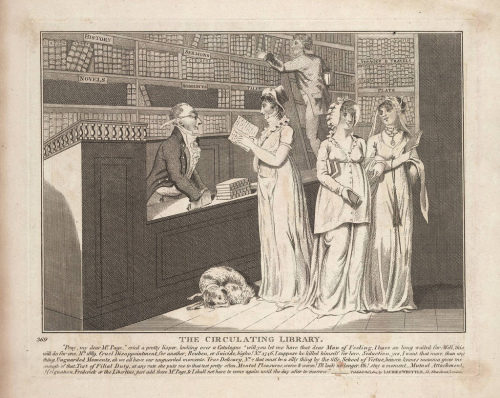

What were the ‘circulating libraries’ of the Regency Era and what was their role in society?

“I have received a very civil note from Mrs. Martin, requesting my name as a Subscriber to her Library which opens January 14, & my name, or rather Yours, is accordingly given. My mother finds the Money. . . . As an inducement to subscribe, Mrs. Martin tells me that her Collection is not to consist only of Novels, but of every kind of literature, &c. &c. She might have spared this pretension of our family, who are great Novel-readers and not ashamed of being so; but it was necessary, I suppose, to the self-consequence of half her Subscribers”

(Jane Austen to Cassandra, December 18, 1798)

In this snippet of her letter, to her sister Jane Austen tells us a great deal about not just herself and her family, but of the nature of the library and the novel in society. What was the nature of a Regency era circulating libraries and what was their role in society? It all had to do with literacy rates.

During the Georgian Era, literacy rates among the ‘common man’ rose. The demand for reading materials increased, driving the rise of two new literary forms, the newspaper and the novel. By 1720, twenty-four newspapers were published in Britain. By the 19th century there were fifty-four newspapers printed in London alone.

The High Cost of Reading

Unfortunately, the cost of reading material did not decrease with the increase in demand. But where there’s a will, there’s a way. People banded together to form “newspaper societies” where groups of people, usually those in a local parish, would contribute a weekly sum. With these pooled funds, the society would purchase subscriptions to one or more newspapers. The newspapers would be shared among those in the society. By 1820, around five thousand of these societies were still going strong.

Whether booksellers took note of the idea or came upon it on their own, they realized that, as with newspapers, there were far more readers who wanted books than could actually afford to pay for them. For some perspective, in 1815, the average (three-volume) novel cost a guinea (a pound and a shilling). Based on the current worth of a guinea’s gold content (keep in mind the price of gold changes daily), that was the equivalent of at least $100 in modern currency.

This doesn’t tell the complete story, though. In the early 1800s, a comfortable middle class salary for a family of four was in the neighborhood of £250. A guinea was slightly more than a pound, but let’s keep the math simple. At the price of a guinea, a typical novel would cost you 1/250 of your yearly income. If you consider the median US income in 2018 as $60,000 (rounding up just a smidge for the sake of the math), then that same novel carries a price tag on the order of $240. Ouch!

Enter the Circulating Libraries

Booksellers, particularly those in big cities like London, had already begun changing their business practices to reflect these economic realities. By the mid-1700s, they encouraged clients to linger at their shops “offering comfortable chairs, a warm fireside in cold weather, some even offering refreshments. The best of these shops soon became places where those with literary interests congregated regularly. Even if a bookseller made enough to afford to employ an assistant or two, most spent a goodly portion of their time in their shops, chatting with their customers. In the days before published book and theater reviews, it was these discussions which enabled people to keep up with the news of the literary world. By the mid-eighteenth century, the social aspects of these literary bookstores were nearly as important as the books they housed.” (Kane, 2011)

From here, it was only a short leap for booksellers to allow their best patrons to take books home with them to continue reading, for a fee, of course. Trustworthy patrons were often allowed to rent books to read and return. The idea grew and by 1728, James Leake had established the first circulating library in England. (Hilden) In 1742 Reverend Samuel Fancourt opened the first circulating library in London. He has also been credited with coining the term circulating library. (Kane, 2011) By the end of the 18th century there were 1,000 circulating libraries across England. (Hilden, 2018)

Libraries Holdings

Early library holdings varied according to the anticipated subscribers of the library. Sometimes existing social clubs or book clubs formed libraries to cater to the interests of their members. These libraries might feature books on science, arts, the classics, law, history, religion or philosophy. Other “club” libraries might feature somewhat broader topics and even some newspapers or magazines which could be made available to members in a separate reading room. These libraries were not open to the public though, available only to members of the club. (Kane, 2011)

Music libraries formed in places like Bath, specifically to allow subscribers access to sheet music. (McLeod, 2017)

Since the circulating library was a business, it behooved the library to cater to as many as could afford the price of a subscription. So, most library catalogs reflected a much wider selection of books, appealing to the tastes of both men and women, since most libraries could not afford to discriminate based on gender. Savvy proprietors quickly realized that the most profitable sort of book was the fashionable novel.

Novels were different from traditional nonfiction books. Where nonfiction works might be read and reread, consulted through the years as a valuable reference, this was not so with the novel. The novel was in fact a “consumable” good. Typically, one read a novel once and never again. It was exactly the sort of book that made little sense to purchase (as an individual) and a tremendous amount of sense to rent.

Library catalogues reflected the (largely female reading) public’s hunger for novels. The average circulating library’s catalogue typically listed around five thousand titles. About twenty percent of those were fiction. However, many libraries boasted multiple copies of those novels, sometimes twenty-five copies. So that twenty percent of titles probably made up a much larger percentage of the library’s actual holdings. Research on smaller libraries, those averaging less than four hundred and fifty titles, reveals collections of up to seventy-five percent fiction titles. Some research suggests that fiction was checked out three to four times as much as nonfiction, implying that for some of these smaller libraries almost all of their stock and trade was in the renting of novels. (Erickson, 1990)

Not only were libraries a place where one could rent books, they were also a place to see and be seen. Watch for the next installment for more on that aspect of the circulating library.

Find References HERE

Find the Regency Life Index HERE

Read more about Regency era Amusements HERE.

Read more about libraries HERE.

If you’d like to read more about Regency era history, you might like these:

Comments

The History of Circulating Libraries — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>