First transitions to manhood: Breeching Boys

While Rousseau’s Émile influenced attitudes toward childhood and childhood dress on the continent, the English ambivalence toward French ideas delayed their adoption in England. However when the Lady’s Magazine 1779 printed their (essentially plagiarized) version of Émile, the idea of simple, comfortable garments for boys gained popularity. “The garb of childhood [it was said] should in all respects be easy, not to impede its movements by ligatures on the chest, the loins, the legs or the arms. By this liberty, we shall see the muscles of the limbs gradually assume the fine swell and insertion which only unconstrained exercise can produce.” (Regency Etiquette, 1997)

Perhaps more significantly, for mothers of boys in particular, the change in philosophy that went along with the changes in garments mean that their young sons did not make the transition from infant boys to men the moment they donned male garments. Instead, of being immediately sent off to apprenticeships or boarding schools, breeched young men would enjoy a slower initiation into the world of men. Fathers would begin spending more time with them, teaching them masculine activities. A tutor might be hired to educate him or he might be sent to study a few days a week with a local vicar, curate, or other resident scholar. And mothers might enjoy a few more years with their young sons at home.

Breeching boys

During the Regency, most boys were breeched at about four years of age, several years earlier than their counterparts from the 1700’s. Child rearing ‘experts’, though, argued for various ages, up to age eight. They agreed though that a child’s size was a most important consideration. Boys who were small for their age or sickly might be breeched later. On the other hand, Boys might be breeched earlier if there was concern that a parent might not live to see their son breeched.

Mothers were primarily responsible for the decision for when their sons should be breeched. Fathers might exert some pressure, though, if the mother delayed the event too long. Social class and standing would greatly influence the nature of the breeching ceremony. For the family with little means, it might be a simple affair or receiving hand-me-downs from an older brother. For the aristocracy, it might be an elaborate affair.

During the Regency, the ceremony rarely took place on the little boy’s birthday. Rather, the convenience of extended family being able to attend the event might be the deciding factor for timing. If the child was the heir of an upper class family, the ceremony was likely to take place at the family’s country estate rather than in a town home. Extended family and close friends, like the child’s god-parents, would be invited to attend.

In preparation for the ceremony, a mother would have at least one new suit of clothes made, assuming she had the means. Otherwise, hand-me-downs might be refreshed for the boy. Cotton or linen shirts, sashes, formal garments and outerwear might also be acquired. Accessories like hats, gloves, stockings and shoes could round out a little boy’s new wardrobe.

No single form existed for the breeching ceremony. With family and friends present, the little boy would make an appearance in his dress, then be led away behind a screen or to another room to change, with assistance, into his first set of distinctive male clothing. In some cases a barber might be present to give him his first masculine haircut. The shorn curls might be given to attendees as mementoes of the event.

Refreshments would be served when the newly minted young man returned in his new clothes. Well-wishers might slip coins or banknotes into his pockets as they congratulated him on his new status.

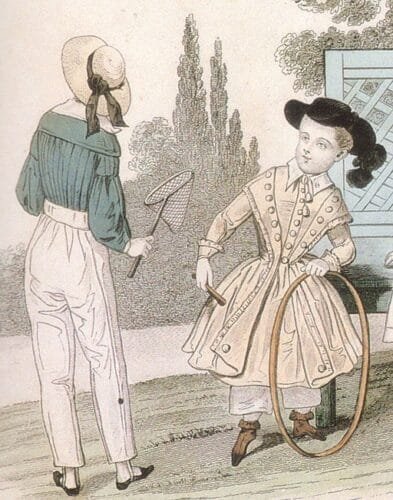

Skeleton Suits

At the end of the 1700’s upper and middle class boys typically wore a skeleton suit after they were breeched and would continue in these garments until around the age of eleven. These suits featured a high button waist, long pantaloons, rather than the knee breeches worn by adult (and adolescent) men, and jackets adorned with many buttons. A blouse with an open, often elaborate collar was worn under the jacket which might be buttoned to the pants to help hold them up. Young boys might also wear pantalettes underneath with a trim or frills showing at the ankles.

Skeletons suits were cut close to the body, but with far more ease in the cut than the skin tight breeches and coats worn by men. Thus, though boys today would likely find them very uncomfortable, boys of the era would consider them neither tight nor constricting. Interestingly, these garments were, due to the influence of Rousseau, considered more healthful and more moral than the more restrictive adult-like garments of early times.

The blouses for the suits were typically white and made of linen or cotton. For every day wear, the pants and jackets might be made of yellow-brown nankeen or other sturdy washable fabrics. Into the 19th century, improved dyeing techniques allowed fabrics to be more colorfast, thus more colorful skeleton suits appeared. During the Regency, dark blue was a favorite color, especially for more formal suits made of silks or velvet.

On special occasions, boys might wear a round straw hat with a brim, and a wide ribbon band or a military style cap. Colorful sashes might also be added to the skeleton suits, tied in large poufy bows around the waist or over the shoulder. To finish their ensemble, boys would wear plain white stockings and flat shoes with a single strap over the instep, typically in black.

Little boys were permitted more latitude in their dress than adult men, particularly when out of the public eye. At times they were permitted to go without the jacket, presumably with some other mechanism to help hold up their pants. Some sources suggest some suits had mid-calf length trousers and short or no sleeves. These were likely reserved for country wear, especially during warmer weather. It is also possible that in summer, skeleton suits might be worn without a shirt at all on very informal occasions.

A fashion conscious mother could keep up with trends in children’s clothing starting in a 1779 edition of the Lady’s Magazine which devoted a small section to children’s clothes. These fashion plates started with girls’ clothes only, but by the Regency, boys’ clothes were included as well since the same seamstresses who made ladies’ clothes also made little boys’ clothes. Children’s fashion illustrations did not appear frequently though. This irregularity slowed the pace of the change in children’s clothing since there were fewer references available for new designs.

Older boys were reluctant to give up the comfort of trousers for the more restrictive breeches and from the skeleton suit came the trousers and short jacket combination that, with a plain linen collar added in about 1820 became the Eton suit. (Downing, 2010)

By 1840, skeleton suits were considered old fashioned and fell out of favor. However, their popularity as children’s wear influenced men’s fashion in the following years. Since the boys who wore skeleton suits did not associate long trousers with working class garb as their fathers did, but rather with comfortable clothing for both casual and formal wear, when they came of age, they did not want to trade in their comfortable trousers for the skin tight, restrictive knee breeches their fathers wore. So trousers rose in status and esteem and breeches slowly fell out of fashion.

Read more about Regency Era childhood HERE

References

“Boys’ Clothes During the 1800s.” Boys clothing during the 1800s. August 27, 2003. Accessed January 07, 2013. http://histclo.com/chron/c1800.html.

A Lady of Distinction . Regency Etiquette, the Mirror of Graces (1811) R.L. Shep Publications (1997)

Adkins, Roy, and Lesley Adkins. Jane Austen’s England. Viking, 2013.

Barreto, Cristina and Lancaster, Martin . Napoleon and the Empire of Fashion Skira (2010)

Black, Maggie, and Deirdre Faye. The Jane Austen Cookbook. Chicago, Ill: Chicago Review Press, 1995.

Brander, Michael. The Georgian gentleman. Farnborough: Saxon House, 1973.

Brooke, Iris. English Children’s Costume 1775-1920 . Dover Fashion and Costumes. Minoela, NY: Dover Publications, 2003.

Collins, Irene. Jane Austen, the Parson’s Daughter. London: Hambledon Press, 1998.

Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Day, Malcom. Voices from the World of Jane Austen. David and Charles, 2006.

Dickens, Charles. Sketches by Boz, 1838-39.

Downing, Sarah Jane. Fashion in the Time of Jane Austen. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2010.

Horn, Pamela. Flunkeys and Scullions: Life below Stairs in Georgian England. Stroud: Sutton, 2004.

Kane, Kathryn. :Boy to Man: The Breeching Ceremony.” Regency Redingote. 31 August 2012. Accessed January 5,2013. http://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2012/08/31/boy-to-man-the-breeching-ceremony/

Kane, Kathryn. “Portent of Pantaloons: The Skeleton Suit”. Regency Redingote. 27 April 2012. Accessed January 5,2013. http://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2012/04/27/portent-of-pantaloons-the-skeleton-suit/

Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press, 2006.

Laudermilk, Sharon H., and Teresa L. Hamlin. The Regency Companion. New York: Garland, 1989.

Lewis, Judith Schneid. In the Family Way: Childbearing in the British Aristocracy, 1760-1860. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Martin, Joanna. Wives and Daughters: Women and Children in the Georgian Country House. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

Regency Etiquette: The Mirror of Graces (1811). Enl. ed. Mendocino, CA: R.L. Shep;, 1997.

Sanborn, Vic. “The well-dressed Regency boy wore a skeleton suit.” Jane Austen’s World. August 17, 2009. Accessed January 7,2013. http://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2009/08/17/the-well-dressed-regency-boy-wore-a-skeleton-suit/

Selwyn, David. Jane Austen and children. London: Continuum, 2010.

Shoemaker, Robert B. Gender in English Society 1650-1850. Pearson Education Limited (1998)

Stone, Lawrence. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Tomalin, Claire. Jane Austen: a life. New York: Random House, 1999.

Vickery, Amanda. The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998.

Watkins, Susan. Jane Austen’s Town and Country Style. New York: Rizzoli, 1990.

Comments

First transitions to manhood: Breeching Boys — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>