What’s Mother to Do?: Infancy during the Regency era

Like so many other facets of society, childrearing also underwent significant changes during the Regency Era. Despite growing concern over the influence of servants in a child’s life, many families of means still employed nursery maids, who might be lower class women, maiden aunts or poor female relations, to tend young children. Parents might have very little contact with their children during nursery days.

Traditionally the nursery was a separate part of the household, running on its own schedule. The exact routine varied from household to household and depended on the number of children and servants to tend them, as well as the servant’s education and beliefs about children.

Customarily, babies would be in the care of the head nurse, while the undernurse had care of the older children. She would awaken the children, typically by 7AM, dress and feed them breakfast, then take them out for air and exercise. Sometime before bedtime (typically around 8PM) the children would be dressed in their best clothes and brought to see their parents for some sort of a visit. Between those times, children would play and might partake in some early lessons, depending on the education of the nurses. Social etiquette would be a major component of those lessons.

But in some, more progressive households, children might be drawn more tightly into the family circle, eating their meals together and even spending time with the family instead of being exclusively separated to the nursery. “The belief was that they would better learn to socialize and grow into better adults by seeing the behavior of their elders and to “practice” with them. But it had the added benefit of keeping the family together and letting the parents and children play a larger part in each other’s lives.” (Olsen 2017)

Children’s health

In an era when child mortality was alarmingly high and many never grew to see adulthood, physicians rarely treated children’s disorders. The reason? Doctor’s remedies were considered too drastic (and thus dangerous) for delicate children. Given their treatments consisted largely of laxatives, bloodletting, and emetics, one can see some wisdom in the strategy.

Instead of physicians, parents often consulted surgeons, who were the hands-on medical professionals, trained through apprenticeship rather than university training. When surgeons were unavailable, undesirable, or unaffordable, parents would look to family members, friends and neighbors for advice, sometimes bringing in very unlikely professionals to assist. For example, sometimes the local blacksmith might set bones for humans as well as animals. (Sometimes it seems a wonder that anyone survived.) (Payne, Health in England) Teething was considered a serious hazard to a child’s life, causing both digestive and nervous complaints. Many superstitions surrounded teething resulting in many charms and recommended treatments for the malady. (Read more HERE)

A unique period of gender equality

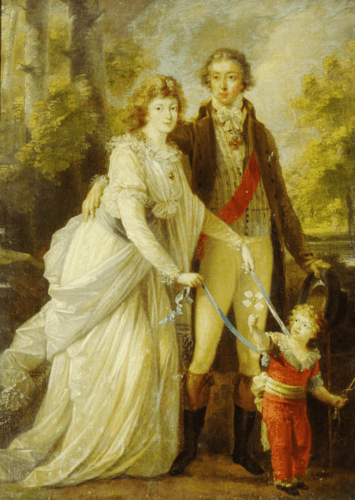

During the Regency, parents felt little need to identify a small child’s gender by their clothing. Those who knew the family personally would already know the child’s gender, and for those who did not know the family that well, it was none of their business. Moreover, very young children rarely appeared in public. The age at which children began to be seen outside the house coincided with the age at which they would begin to wear gender differentiated clothing.

The majority of garments for infants and babies, whether swaddling bands for the first few months of life or simple gowns worn thereafter, were typically linen or cotton, either white or unbleached natural colored cloth, possibly trimmed with colored ribbons. These ribbons would be chosen to the mother’s tastes, not restricted to blue for boys and pink for girls as would be seen much later in the 19th century. In wealthier families, babies had some “good” clothes to wear while being shown off to visiting family and friends. Typically these garments would be colored or trimmed in ways that would not stand up as well to the harsh laundry techniques of the day, so they would be worn sparingly.

One unique feature of infant clothing still present in the early 1800’s was leading strings. Leading strings were the fashion decedents of the hanging sleeves of the middle ages. Attached to the back of children’s garments when the child began to move independently, leading strings might be sewn into individual garments when a family could afford multiple sets. For those of lesser means a single set could be pinned onto different garments. In some cases, children’s garments were made with buttonhole like slits through which leading strings could pass when fastened to the child’s corset.

Well into the nineteenth century infants, both male and female, were dressed in corsets. These garments were not boned and cinched like adult corsets might be, but rather made of multiple layers of sturdy fabric, most often corded or quilted cotton or linen. These garments did not shape the body so much as provide warmth and train the child to have good posture, which was considered essential for good health at that time. The sturdiness of the garment made it an ideal one for attaching leading strings.

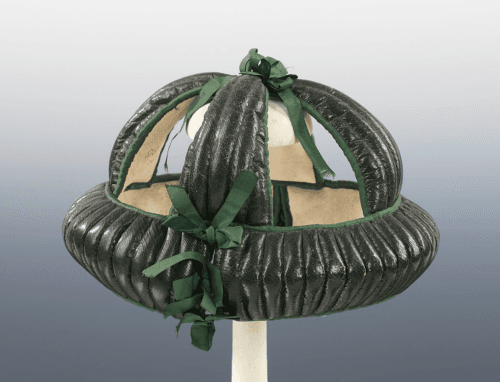

Once attached, leading strings could be used as reins to guide the child during the process of learning to walk. This approach was most prevalent in the upper classes. Pudding caps, a slightly padded helmet of sorts, were also used to help prevent the bumps and bruises that came with learning to walk.

For middle and lower class women who enjoyed less help from servants, leading strings might be used more as a leash to limit a child’s movement. The strings could be fastened to a bed-post or heavy piece of furniture while indoors or something immobile like a fence or tree while outside. Though this might be an uncomfortable idea to modern parents, in a world where child safety measures were largely non-existent, these methods could help keep a child safe while their mother’s attention was diverted elsewhere. Leading strings were usually removed when they learned to walk well, certainly by age three or four.

Before learning to walk, babies wore long gowns that extended beyond their feet. Once out of infancy (walking age), both boys and girls were ‘shortcoated’, dressed in ankle length dresses. The early 19th century saw almost no difference between dresses for little boys and little girls. Little boys might wear their sisters’ hand-me-downs and vice-versa. Dresses might be made of chintz or printed cottons. They were worn with small white caps, sashes and petticoats or long ruffled pantaloons.

Though it is difficult for the modern observer to wrap their minds around dressing little boys like little girls, the fact was that dresses were considered children’s wear, not little girls’ clothes. Children’s dresses were very distinct from women’s garments, so to the eye of the person in context, it was not a matter of boys in women’s garments. On a more practical note, in the days before disposable diapers and washing machines, dresses were much more practical garments for children who were not toilet trained.

Read more about Regency Era childhood HERE

References

“Boys’ Clothes During the 1800s.” Boys clothing during the 1800s. August 27, 2003. Accessed January 07, 2013. http://histclo.com/chron/c1800.html.

Barreto, Cristina, and Martin Lancaster. Napoleon and the Empire of Fashion, 1795-1815. Milan: Skira, 2010.

Black, Maggie, and Deirdre Faye. The Jane Austen Cookbook. Chicago, Ill: Chicago Review Press, 1995.

Brander, Michael. The Georgian gentleman. Farnborough: Saxon House, 1973.

Brooke, Iris. English Children’s Costume 1775-1920 . Dover Fashion and Costumes. Minoela, NY: Dover Publications, 2003.

Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Horn, Pamela. Flunkeys and Scullions: Life below Stairs in Georgian England. Stroud: Sutton, 2004.

Kane, Kathryn . “Regency Baby Clothes: Blue for Boys, ??? for Girls.” Regency Redingote. June 8, 2012. Accessed January 5,2013. http://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2012/06/08/regency-baby-clothes-blue-for-boys-for-girls/.

Kane, Kathryn. “Of Hanging Sleeves and Leading Strings.” Regency Redingote. January 20, 2012. Accessed January 5,2013. http://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2012/01/20/of-hanging-sleeves-and-leading-strings/.

LeFaye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. New York: Abrams, 2002.

Lewis, Judith Schneid. In the Family Way: Childbearing in the British Aristocracy, 1760-1860. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Martin, Joanna. Wives and Daughters: Women and Children in the Georgian Country House. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

Olsen, Quenby. “How to be a child in Regency England.” Jude Knight. May, 1, 2017. Accessed February 18, 2018. http://judeknightauthor.com/2017/05/13/how-to-be-a-child-in-regency-england/.

Payne, Lynda. “Health in England (16th–18th c.),” in Children and Youth in History, Item #166, Accessed February 19, 2018. http://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/items/show/166

Rovee, Christopher. “The Romantic Child, c.1780-1830.” Representing Childhood. 2005. Accessed Feb. 18, 2018. <http://www.representingchildhood.pitt.edu/romantic_child.htm

Selwyn, David. Jane Austen and children. London: Continuum, 2010.

Stone, Lawrence. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Watkins, Susan. Jane Austen’s Town and Country Style. New York: Rizzoli, 1990.

Comments

What’s Mother to Do?: Infancy during the Regency era — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>