Georgian Beauty Ideals

One look at a fashion runway reveals how much beauty ideals have changed through the centuries. How did Georgian beauty ideals influence what would have Jane Austen considered beautiful?

Georgian Beauty Ideals

Life in early modern (1500-1800) societies was rife with injuries and diseases that could result in bodily deformities. Nutritional deficits, disease and accidents could cause sometimes horrific alterations to the human form. Skin conditions, tumors, both benign and cancerous, and conditions like gout marked individuals in all walks of life. Moneyed and poor alike were subject to the debilitating effects to daily life.

Not surprisingly, medical science focused on the prevention and correction of many disfigurements. Progress in infant health and nutrition helped prevent many conditions. Assistive technologies such as wooden legs and rupture trusses improved the productivity and general quality of life for many of those injured.

Assistive technologies quickly crossed the line from improving function to merely improving aesthetics. Some argued whether it was acceptable to attempt to improve upon God’s creation by artificial means. But even the Puritans came to accept man-made means to improve upon nature’s imperfections.

Deformity and Polite Society

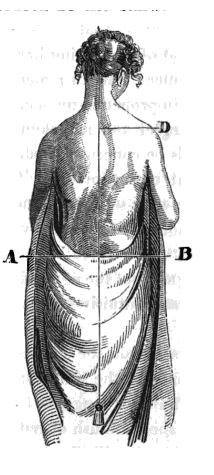

Man lifting female child up by the neck Engraving By: James Hulett Orthopedia or the art of correcting and preventing deformities in Children Nicolas Andry de Boisregard Published: 1743 Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

By the eighteenth century, with the developing culture of politeness, the ‘deformed’ or ‘defective’ body presented a quandary for polite society. Some emphasized the moral virtue that developed as a result of bearing with bodily disfigurement. Others though registered concern for the lack of social ease evident when those bearing obvious ‘defects’ were present.

Etiquette of the period required polite individuals to avoid anything which would draw attention to another’s ‘weakness.’ Thus, mentioning ‘deformities’ was not acceptable in polite conversation. Even so, the imperfect body was often referred to in period literature as dismal and miserable, jarring the sensibilities and discomposing the cheerfulness of mind, stealing pleasure from an otherwise pleasant experience. A crooked body prevented one’s acceptance in polite society, being more prison than palace for the individual residing in it.

Nicolas Andry (1743) suggested that polite society should shun anything ‘shocking’ like visible impairments which might threaten virtuous interactions. Moreover, individuals who permitted, by their neglect, their bodies to become ‘ugly’ offended both society and God’s intentions. Thus, ‘orthopaedic’ intervention to restore the proper aesthetics to the body was an act of social and moral responsibility.

Although these Georgian beauty ideals preceded Jane Austen’s era by decades, they formed the foundation for how those of the Regency era defined and perceived beauty.

That picture was a bit jarring. Bless her heart. Wow! In reference to that quote from Nicolas Andry (1743)… so says someone who considers himself perfect? I wonder if he would have been so vocal if he had an impediment or imperfection? Whew!