Regency Medicine: Betwixt and Between

I’d like to welcome Kyra Kramer today as she shares a fascinating article on Regency Medicine and how it was more medieval than modern.

There would be significant changes in health care in the later decades of the 1800s, with the emergence of germ theory producing biomedicine as we would recognize it by the Edwardian age. The Regency, however, was in some ways the last gasp of medieval medicine – a Tudor merchant would be more familiar with the underpinnings of Regency healing than someone born during the last decades of Queen Victoria’s reign.

For one thing, in the Regency it was still widely believed that illness and disease were caused by “miasmas”, or evil airs. Rotting matter and filth created bad smells, and this bad air would in turn would cause someone to sicken and die if they breathed in too much of it. This was based on a theory proposed by the ancient Greek physician Galen, and was considered beyond contestation by the majority of physicians thousands of years. Anyone who speculated illness was caused by microscopic organisms, as Girolamo Fracastoro speculated in 1546 and Marcus von Plenciz championed in 1762, were stupid quacks and drummed out of the medical establishment.

Moreover, certain foods – like raw fruit and vegetables – were thought to be contaminated with miasmas because they grew in the night air. That’s why people believed for centuries that fruit and vegetables could only be eaten after been cooked, or they would cause violent illness. In reality, the human waste used as fertilizer and a sudden influx of fiber would have been the reason people had a sudden onset of diarrhea, which was life threatening at the time, but for anyone to become sick after eating raw produce was seen as proof of the miasma contamination theory.

Further “proof” of miasma-born illness was produced by cholera outbreaks. Cholera was thought to come from more than one factor, but evil air was considered to be one of the most common sources of contagion. Miasmas were thought to be stronger at lower elevations, because the bad air settled lower, like an invisible fog. The soil near riverbanks and other areas where human waste was disposed of was also thought to produce more miasmas and evil airs of stronger virulence. In London, the areas right on the banks of the River Thames were thought to be prone to cholera outbreaks because they were both low-lying and near water that stank from wastes dumped into it. In truth, it was the human excrement leaking into the well-water from the nearby river that was producing the cholera attacks, but the higher incidents of cholera in those communities was considered to be evidence that the miasma theory was correct.

The best way to combat miasmas was to avoid them, so you would carry around fresh flowers pinned to your person or a perfumed handkerchief in case you ran into a foul stench while out and about. You could also prevent miasmas by keeping your house, yard, and person scrupulously clean. Poor people, who were often deprived access to regular bathing opportunities, were considered disease vectors and it thus gave the upper classes a medical reason (as well as a social one) to avoid viewing the reality of poverty. Miasmas were supposedly particularly potent at night, and you would “catch your death” if you slept with your window open in the evening, so covering the windows of your home with heavy shutters and curtains was seen as preventive medicine as well as a preventive to theft. Sea air, as was recommended for the health of several people in various Jane Austen novels, was supposed to be healthy in that it both blew away miasmas and was the opposite of bad air to breathe. Country air, far from the stinks of city life and urban middens, was also much more healthful than city air. Mountains, with their healthful non-miasma producing soil at higher elevations, were also thought to be bastions of good air. To this day we think of “fresh air” as bracing, and as the air being purer on mountains and at the seashore. This belief is as much a holdover from the cultural understanding of miasmas as it is about the avoidance of modern pollution.

Another major factor in Regency medical beliefs also originated from Galen – humoral medicine. According to this concept, there were four elements in the human body that were combinations of cold/hot and wet/dry, which were represented by the categories of earth, air, water, and fire. Earth was cold and dry, air was warm and wet, water was cold and wet, and fire was hot and dry. Each element made a different kind of “humor”, or biological fluid, in the body: earth made black bile, air made blood, water made phlegm, and fire made yellow bile. People’s health depended on the mixtures of humors inside of them, and when those humors were thrown out of balance illness ensued. The balance of humors could be overset by both internal forces, such as emotion, and external forces like temperature, food, and bad air.

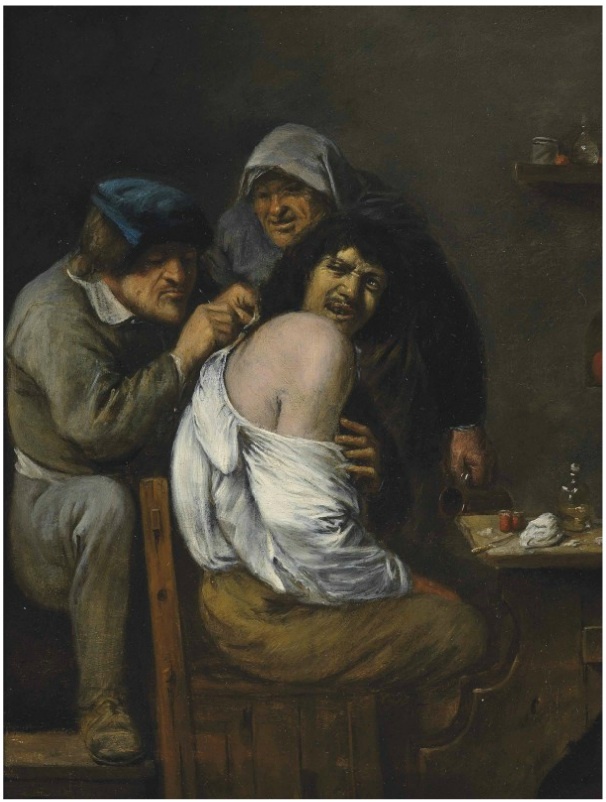

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

One of the most culturally influential books about health, Scots physician William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine: Or, A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases by Regimen and Simple Medicines: with Observations on Sea-bathing, and the Use of the Mineral Waters. To which is Annexed, a Dispensatory for the Use of Private Practitioners, was first printed in 1769 and remained virtually unchanged for the next eight decades. It was considered the home health Bible and the go-to book for medical advice in the Regency, and it was deeply invested in the concepts of humoral theory. It warned that strong negative emotions, like anger, disappointment, and melancholy, could cause apoplexy, a wasting decline, or bring on a fever. An injury could also produce a fever, which makes sense from a modern perspective when we think of infection. Wet feet, abrupt changes of temperature, or extreme temperatures (letting yourself get too hot or too cold) could also lead to sickness or disease. The foods you ate all had “temperatures”, which could kill or cure you. Cholera was most commonly purported to be from miasmas, but it could also be caused by eating “cold” foods like cucumbers or melons, leading to a “derangement” of the intestines. Nevertheless, cold foods — such as barley water and oranges — were also seen as vastly beneficial for lowering a patient’s fever. Everything about maintaining or restoring your health was contextual.

The Regency beliefs about the causes of illness show up repeatedly in Jane Austen’s works. In Sense and Sensibility, Marianne Dashwood almost dies from a putrid fever after she wanders the countryside in inclement weather and then spends an evening sitting in wet shoes and stockings, all while already suffering from disappointment and sadness she has not tried to moderate. Mrs. Bennet uses the agitation she feels after Lydia Bennet’s elopement with Mr. Wickham as an excuse for her supposed bad health in Pride and Prejudice. The eldest son of Mansfield Park, Tom Bertram, becomes desperately ill after drunkenness and a fall brings on a fever, and the various discomforts in transporting him home causes such a relapse that his doctors become “apprehensive of his lungs”. Fanny Price is also given a violent headache by walking across a hot park twice, and is given a glass of “cooling” wine to help alleviate it. In Emma, Mr. Woodhouse is horrified to think of young people at a ball opening a window and exposing themselves to drafts of cold air in a hot room while already heated from dancing and rich food. For Mr. Woodhouse, a hypochondriac who is clearly a little TOO concerned about health, rich food is not only dangerous to the digestion – it is potentially lethal. He eats mainly gruel and soft boiled eggs, and is amazed by the wanton eating of cake at a wedding. Notwithstanding her mockery of Mr. Woodhouse, Austen doesn’t dismisses this ideology altogether; in Mansfield Park Dr. Grant dies after eating several big meals in one week. Finally, Louisa Musgrove is nearly killed in Persuasion when she jolts her spine by landing too hard after a jump, and her altered “nerves” – which the modern reader would assume was the result of a severe concussion and damage to the frontal brain lobes – were implied in the book to be from the “shock” of the injury disturbing her inner equilibrium.

What other incidents of Regency medical beliefs can you think of in Jane Austen’s novels?

Sources:

Buchan, William. 1838. Domestic Medicine: Or, A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases by Regimen and Simple Medicines: with Observations on Sea-bathing, and the Use of the Mineral Waters. To which is Annexed, a Dispensatory for the Use of Private Practitioners. J & B Williams, London.

Hemple, Sandra. 2007. The Strange Case of the Braid Street Pump: John Snow and the Mystery of Cholera. University of California Press. Berkeley/Los Angeles.

Kramer, Kyra. 2012. Blood Will Tell: A Medical Explanation of Henry VIII. Ashwood Press.

Sales. Roger. 1994. Jane Austen and Representations of Regency England. Routledge, London & New York.

Smith, Roger A. 1984. Late Georgian and Regency England, 1760 – 1834. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge/London/New York.

Zimmerman, Barry E. and Zimmerman, David J. 2003. Killer Germs: Microbes and Diseases That Threaten Humanity. McGraw Hill, New York/London/Toronto.

Kyra Kramer is a medical anthropologist, historian, and devoted bibliophile who lives just outside Cardiff, Wales with her handsome husband and three wonderful young daughters. She has a deep — nearly obsessive — love for Regency Period romances in general and Jane Austen’s work in particular. Ms. Kramer has authored several history books and academic essays, but this is her first foray into fictional writing. You can visit her website at kyrackramer.com to learn more about her life and work.

About her latest book: Mansfield Parsonage:

Fans of Jane Austen will recognize the players and the setting–Mansfield Park has been telling the story of Fanny Price and her happily ever after for more than 200 years. But behind the scenes of Mansfield Park, there’s another story to be told. Mary Crawford’s story.

When her widowed uncle made her home untenable, Mary made the best of things by going to live with her elder sister, Mrs. Grant, in a parson’s house the country. Mansfield Parsonage was more than Mary had expected and better than she could have hoped. Gregarious and personable, Mary also embraced the inhabitants of the nearby Mansfield Park, watching the ladies set their caps for her dashing brother, Henry Crawford, and developing an attachment to Edmund Bertram and a profound affection for his cousin, Fanny Price.

Mansfield Parsonage retells the story of Mansfield Park from the perspective of Mary Crawford’s hopes and aspirations, and show’s how Fanny Price’s happily-ever-after came at Mary’s expense.

Or did it?

Books by this author:

Using these affiliate links supports this website!

That’s a really interesting post. My word how much medicine has improved since those times. Lucky for us!!! They did they’re best I suppose with what they had. Can’t wait to read Mansfield Parsonage.

I hope you like it 🙂

So what ails Anne de Bourgh?

At least they had a cure-all for every ailment! Have a fever? Drain your blood. Diarrhea? Drain your blood. Menstrual cramps? Drain your blood. Wound keep bleeding? Drain your blood.

There is a bit too much to chose from to even begin to speculate on Miss De Bourgh (although I suspect hypochondria! or even Munchhausen’s by proxy). Oddly enough, there are a few diseases that actually are helped by blood letting … but so rare as to be useless for most people. Galen did say, however, you should NOT bleed small children or pregnant women.

Fascinating information, Kyra! And you book sounds fascinating. Best of luck with it.

I’m a pharmacist by profession, Kyra, and some of what you’ve posted is familiar to me from the University courses in History of Medicine and History of Pharmacy that formed part of my degree course. One thing I know for sure is that I would definitely NOT want to live in Regency times! No real painkillers apart from laudanum, no antiseptics/local anaesthetics apart from pouring alcoholic spirits over wounds, no antibiotics (though we have overused them!).

Last week I watched the 1996 Sense and Sensibility with Emma Thompson and there was a scene during Marianne’s illness where the doctor had obviously just bled her into a bowl designed especially for that purpose. Kind of brings it home to you how few effective treatments they had, I don’t think Jane Austen actually mentions Marianne being bled (someone correct me if I’ wrong, please) but she does mention how ineffective the doctor’s medicines seemed to be.

Thanks for a fascinating post and good luck with your book!

Pingback:Vertigo in the Regency – Always Austen