Schoolgirl Embroidery in Regency Britain

by Julie Buck

As we look at schools in Jane Austen’s time, and the role of needlework within that schooling, I think it’s important that you understand two things. First of all, you need to know what a sampler is. And secondly, you need to see how girls’ schooling developed from earlier centuries to arrive at what Jane Austen found when she was sent off to boarding school.

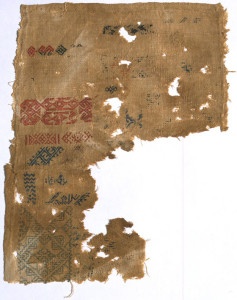

A sampler is an example or sample of stitching – of either patterns or techniques. The earliest written mention of a sampler is from 1505 when an inventory of household items included an “elne of lynnyn for a sampler for the Queen”. That would have been King Henry VII’s wife, Elizabeth of York, who had died in childbirth in 1503, which would explain why the linen was not used by the 1505 inventory.

Sampler 15th century-16th century Linen, embroidered with silk in double running stitch and pattern darning Height 21 cm Width 16.5 cm T.135-192 Location: Victoria and Albert Museum Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum

The first samplers were stitched by women as a pattern record. This was before books were widely available, and even though by about 1650 there were some printed pattern books, it wasn’t until the mid 1800’s that they were readily available to the middle classes, so a lady would keep her sampler rolled up in her sewing box and bring it out when she wanted to use an embroidery pattern to embellish a piece of clothing. The patterns on the sampler would be placed without regard for a pleasing design – they were simply there to jog her memory when the time came to use the pattern. She would copy patterns from her mother, her friends, and from examples she found in any clothing or decorative fabrics.

Jane Bostocke Sampler Location: Victoria and Albert Museum Photo: Julie Buck

Jane Bostocke stitched this sampler in 1598 to commemorate the birth of her cousin Alice Lee two years earlier.

While this sampler was not to be kept in Jane Bostocke’s sewing basket, as it was a commemoration, it was also likely meant as a gift to Alice Lee who would be able to use it in later years as her pattern record. What a wonderful gift this would be – look at the intricate patterns shown here, and compare them to the patterns used in embroidery on these clothes.

On Queen Elizabeth’s clothing, the embroidery is done with gold threads and precious gems, but the patterns are familiar. The cuffs on the Catherine Howard portrait are expertly painted depictions of blackwork embroidery, which was an approximation of detailed lacework – another way to achieve the same look, with a lower cost. Eventually, the embroidery came to be prized for its intricacy, and its reversible property, making it ideal for collars and cuffs.

Queen Elizabeth I by Unknown English artist; attributed to George Gower, oil on panel, circa 1588 National Portrait Gallery, Photo: National Portrait Gallery

Catherine Howard Hans Holbein, The Younger Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art Photo: Toledo Museum of Art

Hans Holbein, The Younger, became famous for his Tudor portraits – there are many of Henry VIII and all his wives. He was so adept at portraying the lavish embroidery on the clothing of these royal personages, that the double running stitch, which produces the blackwork as shown above, has come to be called the Holbein stitch.

As time progressed, samplers changed – the shape was no longer long and thin, but became more square, and skill with a needle was so prized that it became a subject to be taught by specialists. Whether at their mother’s knee, from a dedicated governess, or in an infant school, one of the most important things a girl could learn was embroidery. Think how Jane and Cassandra Austen’s lives would have been so much more mean if they had not the skills to make and embellish their clothing and keep to the current styles.

Over the course of her learning, a little girl in England would soon be working on a curriculum that included four samplers: The first, a simple marking sampler, was taught at the age of five or six. The purpose was to teach a little girl to read her letters, as well as to learn to mark linens for laundry.

Cassandra Austen’s sampler Jane Austen’s House Museum, Chawton

This is Cassandra Austen’s sampler – as you can see, it’s a simple marking sampler, featuring several alphabets, along with some practice rows of very simple decorative bands.

Marking linens with a very simple set of initials, and perhaps a number, was done by every household for several reasons. First, it was to identify your linens as separate from anyone else’s when you sent your linens out to be laundered. Laundry was such a daunting and unpleasant task that you would absolutely send laundry out if at all possible. The number would be to keep track of inventory, and to rotate the use of your sheets, pillow cases, tablecloths and napkins, to ensure even wear. Linen was very expensive, and you didn’t want to be wearing holes in one set of sheets while not using another except rarely. To ensure a long life, all the linens were rotated.

Here we have two examples of marked linens that have survived. The one the left is a sheet with a small monogram in blue in the top left corner. This is where monogrammed sheets, towels, handkerchiefs, etc. came from – it was at first a simple laundry mark, but over time developed into the beautifully embellished pieces we know today.

The one on the right is the number marked on a piece of linen. I wasn’t able to find out what this is, though I suspect it’s a napkin.

The one on the right is the number marked on a piece of linen. I wasn’t able to find out what this is, though I suspect it’s a napkin.

This is the first thing that little girls learned to embroider, whether they were the daughters of wealthy landowners or destitute orphans. In the case of the wealthy, it was important to know how to do this marking so that you could inspect the work of your servants. A poor girl might aspire to work in a grand household and take care of the family’s clothing and linens, and to accomplish this, she would have to know her letters and her stitches.

When Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church, it paved the way for a stop to services being conducted in Latin. Instead of having the word of God interpreted for you by a priest, you were encouraged to have a direct relationship with God, and this included being able to read the bible for yourself. For this reason, almost all small children of middle-class families or better, were taught to read. The sampler was used as a primer for little girls. At this time, children learned to read when they were five or six, but didn’t learn to write until they were older. Very often, little girls were not taught to write at all, as it was thought that they had no need. Boys were taught to write because it was a necessary tool for business, but of course, women would not be in business…

When a little girl was anywhere between eight and ten, she would have been practicing her embroidery skills and would now make a more complex sampler – something like Dorcas Haynes’ sampler:

Front Dorcas Haynes sampler – Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England Photos: Julie Buck

Back Dorcas Haynes sampler – Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England Photos: Julie Buck

You can see that the back of the work is as beautiful as the front – her work was almost entirely reversible, except for the writing. You can also see that the back, which is where we usually look to see the “true colors” of a sampler, shows that the front colors are almost as vibrant as the back, which means that this sampler has not been exposed to very much light. Somebody took very good care of this sampler over the years. This beautiful piece descended in the Haynes’ family until 1950, when it was acquired by the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England.

Rachel Hiatt sampler – Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England Photo: Julie Buck

When you compare this sampler to Jane Bostocke’s, done 122 years earlier, you can see that this sampler was clearly taught in a school environment. Rather than a random placement of elements, the elegant design is pleasing and regular. Unlike the marking samplers, which consist almost completely of marking stitch (a reversible cross stitch), the second sampler of a girl’s school “career” would feature many different stitches and show a girl’s growing competence with a needle. Even though we’re sure that Dorcas Haynes’ sampler was done in a school, please don’t think that every little girl was turning out work like this. This is a masterpiece at any age, and astounding for a girl of 10 to produce. In another few years, a third sampler was produced – this one consisted of both colored and whitework. The stitches continued to grow in complexity and difficulty. The accomplishment of these pieces is truly extraordinary. This is Rachel Hiatt’s work done in 1697 when she was 13.

Whitework sampler – Victoria and Albert Museum Photo: Julie Buck

The final sampler was the most complex of all – this whitework sampler is a masterpiece. That it was stitched by a child seems incredible to us today, yet this is clearly a school piece from the late 17th century.

After her samplers were completed, a girl might go on to do an embroidered picture or make a mirror surround or casket coverings. A casket was just a box – it didn’t have the funereal connotation then that it does today. Many little girls made these beautiful boxes. The very top lifts up and has a mirror inside it. Then at the hinge line, the top comes up, and inside, you have several smaller compartments. On many of the caskets, the bottom front has doors that open to show drawers that pull out. There were usually at least three secret compartments inside – a little girl’s dream. The embroidery would be done by the little girl, and then the embroidered silk sent out to a shop to be applied to a pre-made box.

Martha Edlin casket – Victoria and Albert Museum Photo: Julie Buck

This is Martha Edlin’s casket – she was 11 years old when she stitched it in 1671. Once again, while there were many beautiful caskets made by children, Martha Edlin’s work was extraordinary, especially for her young age. The Victoria and Albert Museum have a number of pieces of Martha’s embroidery – all of it beautiful, and on permanent display in their British Gallery. It’s very unusual to find so many pieces that can be positively identified as to stitcher and date.

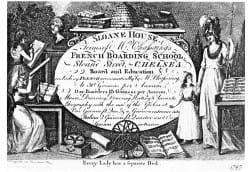

Now, what has all this to do with Jane Austen’s experiences at school? Well, it’s the foundation on which the schools of the Georgian period were based. This is an advertisement from 1797 for a French Boarding School offering instruction of many of the “accomplishments” that were so sought after to make a young lady marriageable. And isn’t it nice to know that every lady has a separate bed for their 30 guineas per annum? These young ladies are learning French, Italian and English grammar, music, dancing, drawing, writing & accounts, and geography with the use of globes. This illustration is topped with a beehive – symbolic of female industry. Who wouldn’t send their girls to a school such as this?

Mrs. Goddard’s school in Emma was one like this.

Here, however, we have a satirical illustration, by Edward Francis Burney, which depicts a multitude of outlandish goings-on imagined to occur at a trendy lady’s seminary. Since this type of criticism was to be found, I think we can assume that Jane Austen was not the only one who looked askance at the type of education available from these seminaries. You can see here young ladies being instructed in music, art (with the master perhaps paying a tad too much attention to the pupil rather than the work), theatricals, art appreciation, dancing, including some kind of oriental dance. I’m not sure what the master in the foreground on the right is teaching, but you can see that “kick me” signs have been around for some time.

Since Caroline Bingley insists that a truly accomplished lady ” possess a certain something in her air and manner of walking “, these young ladies are learning physical fitness while having their posture “improved” by different apparatus, or merely lying flat on the floor. Since the purpose of such schools is to ready a young lady for marriage, one can assume that the young lady seen through the window has graduated as she is eloping out a back window.

In reality, most young people were instructed in a more matter-of-fact way. This is a dame school, or nursery school, and we can see that this lady is taking day students in her home. She is teaching reading, which as I’d said, most young people learned early on. You also see that there are no writing instruments, so there is no writing being learned as yet. You can also see that the mistress is prepared to whip her students into shape!

In reality, most young people were instructed in a more matter-of-fact way. This is a dame school, or nursery school, and we can see that this lady is taking day students in her home. She is teaching reading, which as I’d said, most young people learned early on. You also see that there are no writing instruments, so there is no writing being learned as yet. You can also see that the mistress is prepared to whip her students into shape!

Below is an advertisement for a boarding school which offers to teach young ladies plain work, Dresden, embroidery, Tambour and needlework of every kind. You can see that actual academic subjects are not eschewed, however. English grammar, writing, arithmetic, algebra, geometry and merchants accounts and mensuration (which is a knowledge of measurement). Add to this the needlework, French, music and dancing, and this kind of school is going to turn out some well-rounded young people. Note that this school is for both boys and girls, and parents could pick and choose which subjects their children would study. And you can see that the school master is not giving up his day job!

Brooke, near Norwich

Robert LARKE, having fitted up his House for the Reception of Boarders, begs leave to acquaint his Friends and the Public, that Mrs. LARKE will instruct Young Ladies in plain Work, Dresden, Embroidery, Tambour, and Needlework of every Kind; and that he continues to teach the English Language grammatically, Writing in all the various Hands now in Use, Arithmetic in all its Branches, Merchants Accompts in the Italian, or any other Method, together with Drawing, the Rudiments of Algebra, Geometry, and Mensuration, to those who require a more enlarged Education.

The Terms for Board and Instruction (Washing included) are Fourteen Pounds a Year, and One Guinea Entrance.–And such Young Ladies and Gentlemen who wish to learn French, Music and Dancing, may have an Opportunity of being instructed in all by very capital Masters. Note – He continues to map and embellish Plans of Estates in the neatest Manner.

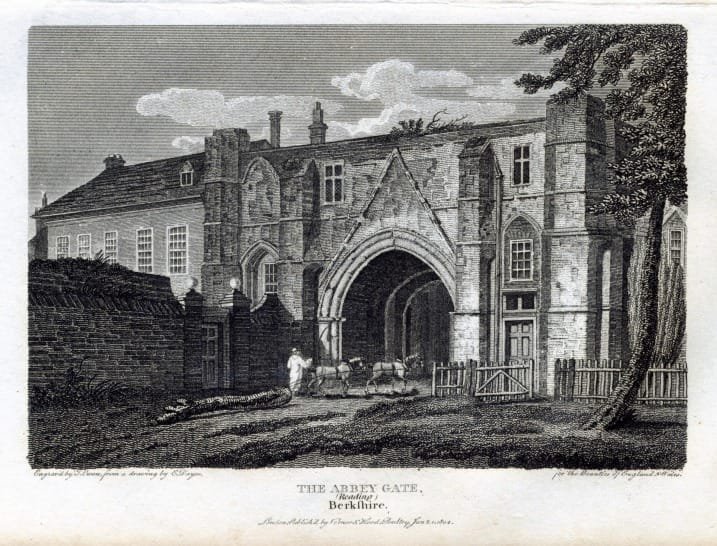

Jane and Cassandra Austen were sent to boarding school at two different times. In 1783, they went to a wife of a cousin in Oxford, and then moved to Southampton. The mistress, Mrs. Cawley, moved to the port of Southampton because of an outbreak of measles in Oxford, but the port city turned out to be more dangerous yet, and almost every student came down with an infectious disease brought into the city from abroad. The children were taken out of school as soon as it was known that the disease had invaded the school. From 1785 to 1786, Jane and Cassandra were students at the Reading Ladies Boarding School situated in the former Abbey Gateway. They were called home after financial reversals in their father’s fortunes necessitated a cutting back of expenses, but these experiences allowed Jane to become familiar with the kinds of schooling available at the time. The rest of her education was accomplished at home, and being in such a literary household, I’m sure there was an emphasis on reading and literary pursuits rather than womanly accomplishments.

While in school, Jane must have started her sampler. I’m sorry to not be able to show it to you – the sampler is in a private collection. The date shows that she finished it after returning home however. While it looks like it’s dated 1797, I’m absolutely positive it originally said 1787. The age of 12 is a much more reasonable age to have stitched such a sampler, not 22. With a flowered border and a pious verse along with the motifs and alphabets, it is surely a school sampler. However, this sampler has not been cared for the same way that Dorcas Haynes’ sampler was. There are fold marks, many holes, and much fading. The sampler was purchased in 1996. According to the sale catalogue, the “seller received the sampler as a present, folded inside a tobacco tin.” A note on the back of the frame states that an early owner was “related to Jane Austen the novelist” and that she had “received it as a memento” of Austen’s life. It is a very simple sampler, and if it hadn’t been stitched by Jane Austen, would have been of little note to anyone today.

Needlework taught in schools was often much more easily seen as practical. The plain sewing sampler shows the student’s skill at eyelets, button holes, patching, joining fabric together, making tabs, and filling with needlelace. The book on the bottom left was a school exercise in different laces. Page after page was made and turned in for a grade. On the right we have a really beautiful darning sampler – each little square, the table, the flourishes, and many of the flowers are filled with pattern darning, teaching the skill of invisible weaving for mending clothing.

Plain sewing sampler – Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York Photo: Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Museum

Lace booklet – Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England Photo: Julie Buck

Darning Sampler Photo: Amy Finkel

Globe samplers – Westtown School, Westtown, PA. Photo: Julie Buck

Geography was a subject that could be taught during needlework class, and this practice came to it’s peak during the 1790’s. On the right, we have a map of Europe, a common subject for a map sampler of the time. The globes were a phenomenon of an American school at that time. Westtown school, in Pennsylvania, is the only place in the world that these globes were made, and they were definitely used as teaching tools. It’s thought that they were made because manufactured globes were too expensive for the school to obtain.

Schoolgirl samplers were often displayed prominently in the home, proof that the family had sent their daughter to school. If there was money enough for that, and if the father thought enough of the daughter to ensure her education, there ought to be a generous dowry forthcoming. Some mothers, feeling their girls had been a little “too long on the vine” have been known to unpick the date on the sampler, to be able to pass the daughter off as some years younger than she actually was. Can we see Mrs. Bennet doing such a thing?

In Sense and Sensibility, Chapter 26, we see Elinor and Marianne being shown to their rooms in Mrs. Jennings’ house in town. “The house was handsome and handsomely fitted up, and the young ladies were immediately put in possession of a very comfortable apartment. It had formerly been Charlotte’s, and over the mantlepiece still hung a landscape in coloured silks of her performance, in proof of her having spent seven years at a great school in town to some effect.”

The caricature below by James Gillray shows a farmer and his wife giving their daughter (just returned from school) a chance to “display” her accomplishments for their neighbors. Note the sampler above the fireplace.

James Gillray 1809

General Assembling Room – Victoria and Albert Museum Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum

The day-to-day life of Jane Austen’s family, and of her characters might have looked something like this. Every time you read of a young lady trying to avoid someone’s eye by assiduously attending to her work, think of this young lady with her embroidery, and her work-basket at her side. You see that the light from the window is coming in over her shoulder to help her to see. Having enough light to work was often a problem, and most work was done by day and in a window.

Throughout Jane Austen’s books, people are quietly working away at something or other. Mrs. Allen in Northanger Abbey and Mrs. Norris in Mansfield Park don’t neglect their embroidery.

Day in and day out, you may expect any of the Bennett girls to be embellishing their clothes or their bonnets with some embroidery – especially Lydia and Kitty. You do see the more “sensible” girls improving their minds, however.

At a time when a woman’s education was primarily thought of as something to prepare her for marriage, you can see how important needlework would be in such a curriculum. But Jane Austen lived in a time of great change – very soon after her death, the curriculum in girls’ schooling would change dramatically, including mathematics and sciences. Within 30 years of Jane Austen’s death, needlework would be banished from female education in England. I’m sure Jane would have breathed a sigh of relief!

In the cartoon , a girl is hung by her neck. They weren’t trying to kill her but to make her stand taller and even, perhaps, make her taller. Maria Edgeworth was a short young lady who was hung by her neck and subjected to other indignities to make her taller. Edgeworth , Austen, Burney, Wollstonecraft, More all wrote out against the education given to girls. They might be able to sew a neat seam but they , supposedly, had their heads full of nonsense.

The samplers and other needlework is beautiful. I never would have finished primary school if I had been required to make a sampler. Still, I think it a shame that it has been banished. More people will have to sew something than will ever need higher math, advanced science or a knowledge of Shakespeare.

Well, I’m English and 63, only 63 I say because we had to sew a sample of various stitches in primary school. Nothing like as complicated as these, just a line of each stitch in embroidery. This was in the 60s. But I think it faded soon after. 1963-5 in Northamptonshire

Yes, Nancy – I thought that particular “exercise” looked like torture! I, too, wish that I’d been required to learn needlework while I was younger, but perhaps I wouldn’t have appreciated it then, as I do now. And of course, the examples given are mostly of the most gifted in needlework – not every little girl could make such magic with her needle. I think it was a very good thing when girls were finally taught mathematics, science and other highly academic subjects, but we did lose a little something, I think, when we stopped needlework altogether.

Pingback:Paying Calls and Visits - Random Bits of Fascination