Circulating Libraries and the Regency era Novel

In honor of National Library Week, I’m reposting this series on the libraries of Austen’s day.

What made circulating libraries so important to Georgian era women and what was the role of the humble Regency era novel in the whole affair?

James Fordyce, in his Sermons to Young Women, counsels strongly against novels, the very sort of books offered by local and easily accessible circulating libraries. (Despite the face he had not read them, of course. But I digress…) He declared:

What shall we say of certain books, which we are assured (for we have not read them) are in their nature so shameful, in their tendency so pestiferous, and contain such rank treason against the royalty of Virtue, such horrible violation of all decorum, that she who can bear to peruse them must in her soul be a prostitute, let her reputation in life be what it will be. Can it be true . . . that any young woman, pretending to decency, should endure for a moment to look on this infernal brood of futility and lewdness? (Fordyce 176-177).

Jane Austen and the Circulating Library

Happily for all of us, Jane Austen did not seem to share that sentiment. Not only was she a subscriber to circulating libraries, her patronage was sought after. On December 18, 1798, she wrote to her sister Cassandra: I have received a very civil note from Mrs. Martin requesting my name as a Subscriber to her Library which opens the 14th of January, & my name, or rather Yours is accordingly given. My Mother finds the Money … As an inducement to subscribe, Mrs. Martin tells us that her Collection is not to consist only of Novels, but of every kind of Literature, 8cc. &cc.- She might have spared this pretention to our family who are great Novel-readers and not ashamed of being so;-but it was necessary I suppose to the self-consequence of half her subscribers.” (Letters 38-39). So while Austen was very accepting of novels, the local librarian realized the concern and tried to address it, even as she worked to drum up patronage for her business.

What made circulating libraries so important to not just Jane Austen, but Georgian era women in general and what was the role of the humble novel in the whole affair?

Libraries as refuges of the female middle class and gentry

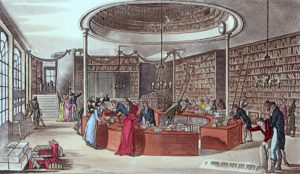

During the late Georgian and Regency eras, there were few public spaces which could be enjoyed by women of good reputation, but limited means. Tea, coffee and chocolate houses might be enjoyed, if one could afford them. But women had no clubs like men did—a place to offer refuge from the day to day. They did though have the possibility of the circulating library.

Though libraries did require a subscription in order to rent books, one could go to the library whenever she wished without paying a fee beyond that subscription. Not surprisingly, circulating libraries became fashionable meeting places for women to see and be seen by others. They offering their patrons sitting areas were raffles and games could be played; some offered expensive (and often distinctly feminine) merchandise for sale. Perhaps most significantly, they offered women an opportunity to read on a large scale including histories, philosophies, biographies, travel, poetry, and plenty of fictional works. (Hilden, 2018) Austen seemed to use the character of Fanny Price to suggest that circulating libraries could ideally be a means for the intellectual liberation of women of small means. (Erickson, 1990)

Not everyone held such positive attitudes toward circulating libraries. Considering libraries largely originated as repositories of theological publications, one cannot escape the irony that by the end of the eighteenth century, circulating libraries drew criticism as sources of corruption. Critics, like Fordyce, suggested that the novels that made up the as much as seventy five percent of a circulating library’s business were responsible for encouraging idleness as well as corrupting the taste and morals of young ladies especially.(Kane, 2011) Many believed that reading novels would give impressionable (and somewhat irrational) young ladies unrealistic expectations about life. (Hilden, 2018)

Libraries and the Rise of the Novel

Publishers also registered concerns about the circulating library, afraid that it would negatively impact their business. But James Lackington, proprietor of the Temple of Muses, noted in the 1794 edition of his memoirs, “thousands of books are purchased every year, by such as have first borrowed them at libraries.” (Erickson, 1990) Moreover, publishers found that increasing numbers of their print runs were purchased by circulating libraries. In 1770, about forty percent of a novel’s print run were sold to libraries. That number increased into the early nineteenth century. (Erickson, 1990)

To economize somewhat, libraries ordered their books with the cheapest possible bindings. Home libraries usually ordered books in cloth or, more expensive, leather bindings. Circulating libraries used a conspicuous marble patterned paper binding that distinguished library books from all others as Austen noted in the way Mr. Collins identified a library book in Pride and Prejudice. These cheap bindings also meant the books lacked the durability of privately owned books and, surviving copies of some of the period’s novels are very rare. (Erickson, 1990)

Libraries as publishers

In order to keep up with demand for new books, later in the 18th century, some of the circulating libraries began to take on the role of publisher as well. Although they lacked the broad distribution channels that traditional publishers had, they held a unique distinction.

Unlike traditional publishers, these smaller presses published many works by female authors, although these were often published anonymously to avoid prejudice by the reading public.

Minerva press

Minerva Press Circulating Library in London, created by John Lane, was the largest circulating library in the 18thcentury. The library advertised over 20,000 titles, compared to the 5,000 titles most libraries averaged, with 1,000 considered works of fiction. (Hilden, 2018) Minerva Press, became known for printing Gothic horror and sentimental romance novels, including The Mysteries of Udolfo by Mrs. Radcliffe (that Catherine Morland read during Northanger Abbey.)

Though some argued that were hurriedly written to a formula by obscure women writers, these publishers “changed to course of publishing and really opened the door to the social acceptability of female authors, as well as created a better variety of fictional novels.” (Hatch, 2014)

It is interesting to note how much the impact of circulating libraries on publishing resembles the transformation of the publishing industry in the first decade of the 2000’s with the advent of the e-reader and electronic publishing down to the criticisms offered toward authors and books published by them.

Find References HERE

Find the Regency Life Index HERE

Read more about Regency era Amusements HERE.

Read more about libraries HERE.

If you’d like to read more about Regency era history, you might like these:

Maria, as always, I appreciate your sharing information about the history of England’s circulating library. As a child, the library was my favorite place in the world. It was where I checked out Laura Ingalls Wilder’s collection of “Little House On the Prairie” books and Langston Hughes collection of “Simple” books. I also read and researched homework as well, but the library was such a wonderful place for me. I can certainly understand why Regency women would flock to it and why others would feel threatened by it but would eventually come to appreciate it.