Regency Girl’s Education pt 3~How were They Taught?

While most schools and formal education opportunities were aimed at boys, Regency era girls also received an education aimed at preparing them for their future lives.

The question is though, just where did a young lady acquire her accomplishments? With no universal school system in place, education for both girls and boys could be a hit or miss proposition. As with boys, though, girls learned at home, taught by mothers, governesses, masters and tutors, and, depending on a family’s financial status, in boarding schools.

Children of the working classes could learn reading and perhaps basic math though dame schools and Sunday schools. Apprenticeships in trades were also still an educational path during the Regency Era, although it was most often boys who profited from those experiences.

Education at Home

Girl’s education was a bit of a controversial subject. Girls from affluent homes were often educated by their mothers, since they could hire enough help with the household work to have time to invest in their daughter’s education. Families might also enlist the aid of additional teaching assistance in the form of governesses, tutors, and masters for training in music, languages and dance, depending on their resources.

These professionals differed widely in their preparation, pay, and the expectations placed on them. A governess was an educated woman brought into a family’s home to teach their children. Very often she was an impoverished woman of the same class as the family who hired her. She would have a boarding school education, the quality of which might be dubious, and the unenviable situation of having to work to support herself.

Governesses existed in a strange grey space between the family and other servants. Below the family as hired help, only rarely did the family include her in their society. But since she was generally born to a higher social class, she did not fit with the servants, either. Often mothers were jealous of the affection her children showed the governess. Male household members might impose upon the governess for other, ah, lets call them services, although her reputation needed to be impeccable. All in all, it was not an easy or enviable life. And all this for an average wage of £20 to £40 a year, although some very rare few could make £125 to £200 a year. Room and board were considered part of the contract as well.

What a governess taught would depend on her own skills. Typically, reading, writing, mathematics, languages, art, needlework, geography or history were standard offerings. Since she usually came from a similar social class to her students, a governess might also teach deportment, social graces, and perhaps music.

Tutors were men, some young, some older, typically hired to teach boys and prepare them for eventual university study. In families where the father values additional education for his daughters, a tutor might be hired to supplement a governess’ efforts.

Tutors typically attended university, but might or might not have a degree. Often, they were clergymen without a parish (a not uncommon problem in the era), those whose parish provided only a small income, or curates whose vicar paid them as meanly as he possibly could. Their income was variable, but they could make a much as £100 a year tutoring the sons of a wealthy family. They taught academic subjects, frequently Latin, based on their own competence.

Masters differed from governesses and tutors in several significant ways. First, masters specialized in particular skills or accomplishments. Masters might be hired for dancing, drawing, training on musical for instruments or voice. Riding and fencing master were also available, though their services were generally restricted to male students. Masters might visit the students at home to train them, but they did not generally live at the student’s home. They might also have their own establishment to which the students would come for instruction.

Even with education provide at home, at the age of ten, parents might consider sending their daughter to a boarding school, sometimes for as little as a year or two to ‘finish’ their accomplishments. If a girl was in the way at home, she might be sent off earlier or for much longer.

Boarding Schools

During the latter 18th century and the early19th, the number of Ladies Seminaries, private boarding schools where the daughters of the middle classes and the gentry could be educated, at a variety of price points, exploded. Parents desiring to provide their daughters with upward social mobility flocked to them, as did otherwise unsupported, educated women seeking positions as teachers. These women included clever, but poor former students, impoverished gentlewomen, poor relatives of the clergy or retired servants of the upper classes, all needing income and desiring a position better than a governess’.

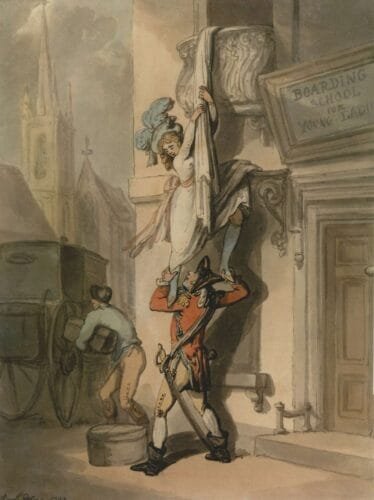

Although on the surface it might seem an excellent solution for rounding out a girl’s education, boarding school had its risks. No matter how good a school’s credentials looked, it was difficult to be certain of the level of supervision and safety she would experience there. Many girls’ schools were underfinanced, badly managed, and never quite managed to be completely respectable. Elopements from boarding schools were not unheard of, and for a well-heeled family, such a thing could be disastrous.

Not everyone considered Ladies’ Seminaries useful. One (female)

correspondent, writing to The Lady’s Magazine (1810 ) voiced a decidedly

negative opinion: “…every town for miles round London, … can boast two

or three, or sometimes four of these seats of learning; and we not unfrequently

see … ‘Ladies Seminary’ in a country village; the governess of which is

usually as ignorant as those she undertakes to teach. To these places are the

children of farmers, mechanics and traders sent; where, at an enormous annual

expense, they are taught dancing, music, and what are called fancy-works; this,

with a superficial knowledge of French, for the most part, completes their

education; for, as to their own language, they are not sufficiently acquainted

with it to allow them to indite a letter, or even spell it correctly. “

What did these school teach?

Actual instructional offerings would depend on the competency of the available teachers. Polite literature, including mythology, writing, arithmetic, botany, history, geography, and French formed the balance of the academic subjects. Nonacademic subjects like sewing and fancy needlework, drawing, dancing, music were equally important parts of the curriculum. Rudiments of stagecraft and acting might also be taught as training in elocution and grace of movement. Parents typically paid twenty to thirty guineas (a pound plus a shilling) per year for these schools. Some of these subjects, particularly those which required additional masters to be brought in, like dance, might incur additional fees. Washing and the privilege of being a ‘parlor boarder’ who enjoyed extra privileges like eating with the mistress of the school and using the parlor, also cost extra.

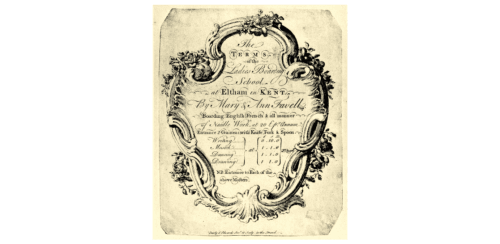

This 1755 advertisement for a Ladies Boarding School in Ken advertises boarding, English, French and all manner of needlework for twenty pounds per year, though the lady must bring her own knife, fork and spoon. (Yes, really, that was a thing, travelers often packed their own cutlery for a trip, but I digress…) Writing, music, dancing and drawing all could be added for additional fees.

This advertisement from 1797 for a “French Boarding School” offers every lady has a separate bed for their thirty guineas per year, in addition to instruction in French, Italian (for an extra fee) and English grammar, music, dancing, drawing, writing, accounts, and geography with the use of globes. This school also took local pupils who did not live on site for fifteen guineas a year.

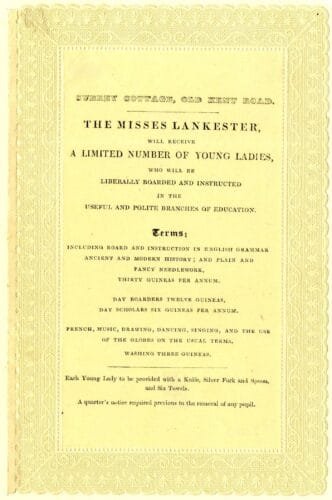

Around 1800, the Misses Lankester offered instruction in the useful and polite branches of education. For thirty guineas a year, girls would learn English grammar, ancient and modern history, plain and fancy needlework. French music, drawing, dancing, singing, and the use of globes could be added for additional fees. If a family wanted a girl’s laundry done, that would come to an additional three guineas a year. In this case, a young lady was to arrive with not only her knife, silver fork and spoon, but with six towels as well. Local students could attend without boarding there for twelve guineas a year, with meals, and six guineas a year without.

Girls could be sent to boarding schools for reasons other than just for their education. For some families, getting the girl(s) out of the way at home, either because they were bothersome, or because the space they consumed was needed for other purposes, became the key motivation. Walker (2005) makes an interesting case that this was the case for Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra. Jane Austen herself went to two schools between the ages of seven and eleven. The first was Mrs. Cawley’s school at Oxford (later Southampton) and the second was Mrs. La Tournelles’ school in Reading. Walker suggests that they were sent away, at least in part, to make room for their father to take in more (male) students, who would bring in more income than boarding school for the girls cost. Her article is linked in the references below if you’d like to read more on that.

Once her education was finished, what was next for Regency Era girls? Stay tuned for the final part of this series.

What do you think of the educational resources for Regency girls? Tell me in the comments.

Click here to read more about Regency Era education

Click here to read more about accomplishments in the Regency Era.

Click here to read more about Ladies in the Regency Era.

Click here to go to the Regency Index.

References

Baird, Rosemary. Mistress of the House, Great Ladies and Grand Houses. Phoenix (2003)

Collins, Irene . Jane Austen, The Parson’s Daughter Hambledon (1998)

Collins, Irene . Jane Austen & the Clergy The Hambledon Press (2002)

Davidoff, Leonore & Hall, Catherine. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850 Routledge (2002)

The Female Preceptor. Essays On The Duties Of The Female Sex, Conducted By A Lady. 1813 and 1814

Fullerton, Susannah. Jane Austen & Crime JASA Press (2004)

Harvey, A. D. Sex in Georgian England Phoenix Press (1994)

Ives, Susanna Educating Your Daughters – A Guide to English Boarding Schools in 1814, March, 10 2013.

Jones, Hazel. Jane Austen & Marriage Continuum Books (2009)

Lane, Maggie. Jane Austen’s World Carlton Books (2005)

Laudermilk, Sharon & Hamlin, Teresa L. The Regency Companion Garland Publishing (1989)

Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels Harry N. Abrams (2002)

Martin, Joanna. Wives and Daughters Hambledon Continuum (2004)

Murden, Sarah. Education, Education , Education—for Girls in the Georgian Era. All things Georgian. November 21, 2022. Accessed June 27, 2024. ttps://georgianera.wordpress.com/2022/11/21/education-education-education-for-girls-in-the-georgian-era/

Selwyn, David. Jane Austen & Leisure The Hambledon Press (1999)

Sullivan, Margaret C. The Jane Austen Handbook Quirk Books (2007)

Walker, Linda Robinson. Why Was Jane Austen Sent away to School at Seven? An Empirical Look at a Vexing Question. PERSUASIONS ON-LINE. V.26, NO.1 (Winter 2005). Accessed August 7, 2024. https://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol26no1/walker.htm

Watkins, Susan. Jane Austen’s Town and Country Style Rizzoli (1990)

Vickery, Amanda. The Gentleman’s Daughter. Yale University Press (1998)

Comments

Regency Girl’s Education pt 3~How were They Taught? — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>