Educating Boys: the Early Years

Today, children spend a great deal of time in formal schooling, so much so, it is hard to imagine childhood without it. But in the early 1800’s, formal schooling was far from a given for many children.

In all well-regulated states, the two principal points in view in the education of youth, ought to be, first, to make them good men, good members of the universal society of mankind; and in the next place to frame their minds in such a manner, as to make them most useful to that society to which they more immediately belong; and to shape their talents, in such a way, as will render them most serviceable to the support of that government, under which they were born, and on the strength and vigour of which, the well-being of every individual, in some measure depends.

(Sheridan, 1756)

Early education

Although some sentiments supported the education of youth (read here, male youth; female education would not be considered worthwhile yet for quite some time), no one really argued for state provided education for middle and upper class children before 1850. (Brown, 2011) Their education was left entirely in the hands of the parents. Although considerable effort and activity might have gone into educating these children, it was hardly standardized. How a young boy was educated depended entirely on the preferences and means of his family.

On the whole, early education in the home was preferred. Mothers and governess would provide a boy’s first education, often teaching him the basics of reading and writing. Usually by the age of seven he would graduate from being taught by women to being educated by men. There were no standards of how this worked though. The specific detail of varied by family and by class.

A male tutor might be brought into the home to teach the child, preparing him for the next step in his education. This could continue for just a few years until the boy was deemed ready for a boarding school, or it could continue until he was ready for university study, depending on the education philosophy of the family, usually the father. (Selwyn 2010)

Alternatively, a boy might be sent to a local scholar, often a clergyman, for lessons as a day student. Many clergymen also took such students on as boarders, running small schools to supplement their income teaching anywhere for half a dozen to two dozen students.

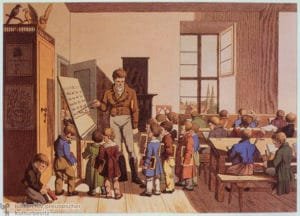

Preparatory Schools

These smaller schools which routinely took boys in the 7 to 13 year old age range were often referred to as preparatory schools, preparing boys for the larger public schools that often preceded entry into the universities.

These schools were usually held in the schoolmaster’s home. Jane Austen’s father, Rev. George Austen conducted such a school out of the vicarage in Steventon beginning in 1793. His living as a vicar was £230 a year. He charged £35 per term for each of his student boarders. It is easy to see how taking even just a few students could substantially augment his family’s income. The work though did not fall on him alone. His wife cooked, cleaned, sewed, and mother-henned the boys in her care, much like a surrogate mother. (Sanborrn, 2016)

In larger schools where the teaching staff consisted of ordained clergymen, teachers could make as much as £200-400 a year, giving them a comfortably middle class income. (Davidoff 2002) Headmasters in such schools, especially if scholars themselves, might enjoy a position of respect and distinction in local society. (Selwyn 2010)

Teachers and Curriculum

By modern standards, preparatory school curriculum was very limited. It consisted mainly of Latin and Greek classical texts (both prose and verse), modern and ancient history, some mathematics, and the use of globes to locate nations. French and Italian might be taught as extras (for additional fees), along with handwriting, dancing, drawing and a smattering scientific subjects. (Le Faye, 2002) No curriculum standards existed, so what might actually be taught varied widely and there was not guarantee that a particular teacher was actually well versed in the subjects he taught.

Teachers in these preparatory schools were most often clergymen or failed ordinals. There were far more men ordained than there were livings to provide for them. In 1805, it was estimated that up to 45% of those ordained never found a church living and were forced to work as (usually highly underpaid) curates for men who had a living, or to try their hand at teaching or take up another occupation entirely outside the church. (Southam, 2005)

After their education in these preparatory schools, boys might then progress to a public school.

I so appreciate your research and commitment to accuracy in your books when it comes to historical details! I just finished another author’s book that was full of anachronisms that drove me nuts.