Christmas Pantomime Tradition

In Jane Austen’s day, theaters prepared Christmas pantomimes (pantos) that would begin on Boxing Day and run as long as the audiences demanded them. Although pantomimes had begun as a crowd-pleasing mix of humor, mime, special effects spectacles, song and dance, based on the Italian commedia dell’arte, by the late Georgian era, the panto had become a well-established part of Christmas tradition.

History of Pantomimes

The tradition of pantomimes and the pantomime characters in England traces back to medieval theater. Broadbent (1901) notes:

A sketch of Harlequin’s original (medieval) part is worth recording. ‘He is a mixture of wit, simplicity, ignorance, and grace, he is a half made up man, a great child with gleams of reason and intelligence, and all his mistakes and blunders have something arch about them. The true mode of representing him is to give him suppleness, agility, the playfulness of a kitten with a certain coarseness of exterior, which renders his actions more absurd. His part is that of a faithful valet; greedy; always in love; always in trouble, either on his own or his master’s account; afflicted and consoled as easily as a child, and whose grief is as amusing as his joy.’ His costume consisted of a jacket fastened in front with loose ribbons, and pantaloons of wide dimensions, patched with various colored pieces of cloth sewn on in any fashion. His beard was worn straight, and of a black color; on his face he had a half black mask and in his belt of untanned leather he carried a wooden sword.

Broadbent, 1901

The first ‘modern’ Pantomime appeared on the English stage in 1702. Produced at Drury Lane, ‘Tavern Bilkers’ was written by John Weaver, a dance-master who would go on to write and produce a number of pantomimes. But it was John Rich, an actor who played Harliquine, beginning in 1717, who brought the Harlequinades Pantomime into its own, creating a new form of dramatic composition. Though initially silent performances, pantomimes developed into very verbal performances that included the audience as an extra character in plays bearing many similarities to modern burlesque.

It consisted of two parts, one serious, the other comic; by the help of gay scenes, fine habits, grand dances, appropriate music, and other decorations, he exhibited a story … Between the pauses of the acts he interwove a comic fable, consisting chiefly of the courtship of Harlequin and Columbine, with a variety of surprising adventures and tricks, which were produced by the magic wand of Harlequin; such as the sudden transformation of palaces and temples to huts and cottages; of men and women into wheelbarrows and joint stools; of trees turned to houses; colonnades to beds of tulips; and mechanics’ hops into serpents and ostriches.

Broadbent, 1901

In 1732, John Rich built Covent Garden Theater with the profits from his popular pantomimes.

Pantomimes were often performed as after pieces following other plays, as part of an entire evening of entertainment and merriment. In the 19th century, the serious portion of the evening dwindled in importance and duration as the performance of the harlequinade portion and the role of Clown of the evening became increasingly popular.

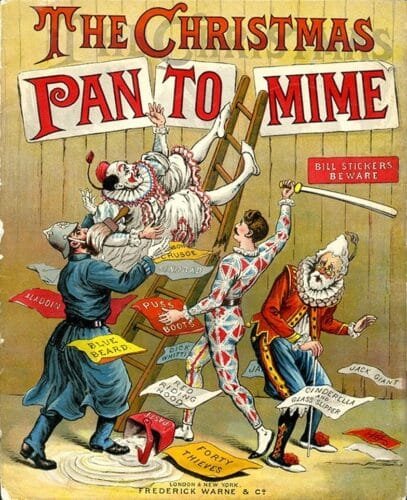

Panto Stories

Arguably, one of the characteristics that made the pantomime so popular was its ability to blend a variety of themes and plots with the story that made up the panto’s core: Harlequin loves Columbine, but her greedy father Pantaloon tries to separate the pair in league with his servant Clown, an agent of merry chaos.

Most of the pantos merged children’s fairy tales or stories like Robinson Crusoe or Sinbad the Sailor, with the fantastical star-crossed lovers of the harlequinade story. Dual titles, like ‘Harlequin and Cinderella,’ paid homage to both elements of the production. Typically, the panto began in the fairy-story world with a cross, old, business-minded father trying to force his pretty daughter to marry a wealthy fop despite her preference for another, worthy though poorer, suitor. Harlequin would use his ‘slapstick’ (which became the terms for the panto’s particular style of tomfoolery and physical humor) and the good fairy transformed the lovers into the harlequin characters in a spectacular scene of magic. As stage machinery and technology improved, the transformation scene became more and more remarkable. Once the transformation was complete, Clown (and the audience with him) cried, “Here We Are Again”.

The new setting usually contained multiple stage traps, trick doors and windows. Clown would jump through windows and reappear through trap doors as he enacted the most dramatic, and beloved, part of the production, the frenzied chase scene. He would steal sausages, chickens and other props, grease doorsteps to outwit pursuers, use his magic wand to turn a dog into sausages or a bed into a horse trough, to the surprise of the sleeping victim.

Actor-Manager David Garrick of Covenant Garden’s rival, Drury Lane Theater, brought his own take to pantomime by adding speech to the Harlequin’s role and hiring Henry Woodward (a pupil of John Rich’s) to craft new stories for the pant, some based on English folk tales, some entirely new, with a heavy emphasis on satire. Ironically Garrick considered pantomime a low form of art and limited the panto performances at Drury Lane to the Christmas holiday season.

Characters

John Rich developed the major pantomime characters that became the standard characters found in nearly all future pantomimes: Harlequin, Clown, Columbine, and Pantaloon from the original company of characters that included Punch, Scaramouche and Pierrot as well.

Harlequin

Harlequin was the romantic male lead, though the role was distinctly more comedic than traditionally romantic. A mischievous magician, Rich’s Harlequin used his magic batte or “slapstick” to transform the scene from the opening pantomime setting into the fanciful harlequinade and to magically transform the settings during the chase scene. In the 1800’s Harlequin became more romantic and mercurial than magical and comedic.

Columbine

Columbine was the beautiful love interest of Harlequin, daughter of Pantaloon, a devious, greedy merchant, bent on keeping the lovers apart with the assistance of Pierrot, his servant, and Clown.

Pantaloon

In the original commedia dell’arte, Pantaloon, or Pantalone in Italian, usually wore a tight red vest, breeches, skullcap and slippers. With a prominent hooded nose and goatee, the greedy merchant was easy to recognize. In Rich’s version of the harlequinade, Pantaloon was no match for clever Harlequin and his servant, Clown usually was more hinderance than help. As the panto evolved, Pantaloon became Clown’s assistant.

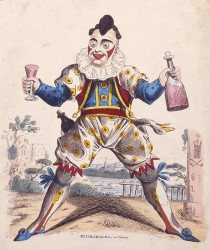

Clown

Clown began as a servant to Pantaloon, a comical idiot dressed in tattered servant’s garb. In the 1800’s new costumes and new actors, like Josepeh Grimaldi transformed the role to an undisputed agent of chaos with jokes, catch phrases and songs that audiences would shout and sing along with. “Clown became central to the transformation scene, crying “Here we are again!” and so opening the harlequinade. He then became the villain of the piece, playing elaborate, cartoonish practical jokes on policemen, soldiers, tradesmen and passers-by.” (Broadbent, 1901)

As an actor, Grimaldi played a transformational role in both the character of clown in the panto, and on modern-day clowns. He essentially invented gags like objects coming to life, slipping on banana skins, tormenting other characters and fighting with authority figures. He changed the traditional costume into something akin to the stereotypical circus clown with think of today with white face, red cheeks, and oversized pants. (Savage, 2018)

Pantomime had its critics

Though the panto was, on the surface, a heady mix of mirth and mayhem, the business of real life intruded through a heavy dose of satire. Through his role as clown, “Grimaldi offered humorous and ridiculous commentary on technology, politics, new forms of transport and fashion.” (Thomanm, 2018)

Journalist “Leigh Hunt particularly felt the medium’s satirical force. In 1817 he called it the age’s “best medium of dramatic satire”. But by 1831 he was grumbling that: “It is agreed on all hands that Pantomimes are not what they were… Pantomimes seem to have become partakers of the serious spirit of the age, and to be waiting for the settlement of certain great questions and heavy national accounts, to know when they are to laugh and be merry again.’” (Saville, 2015)

Panto Audiences

While one part of the performance was aimed at the children and the innocent, adults responded to the often risqué or politically charged verbal exchanges.

Theatre patrons consumed large quantities of alcohol and food, and people arrived and left throughout the performance. Audiences chatted among themselves, and sometimes pelting actors with rotten fruit and vegetables if dissatisfied with the performances. (Baer, 1992

Since the audience participated in the show, emotions could run high. So much so, a pantomime could, and occasionally did, incite a riot.

Conclusion

From the start, pantomime was an art form of adaptation and novelty, with only the major themes, like good triumphs over evil, and young love defeats all obstacles remaining consistent. In keeping with that tradition, pantomime inspired other popular entertainment forms. Punch and Judy theater came from the original clown character Pulcinello. Circus clows and manic chase scenes found in slapstick comedies through the ages from the Keystone Cops to Benny Hill and Monty Python, all find their origins in the panto.

Read More about Regency Theater Here

Read More about Home Theatricals Here

References

Baer, Marc. Theatre and Disorder in Late Georgian London. Clarendon Press. 1992

Brand, Emily. What are the origins of the Christmas pantomime? History Extra. December 2, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.historyextra.com/period/georgian/christmas-pantomime-origins-start/

Broadbent, R. D. A History of Pantomime. by R.j. Broadbent. S.l.: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, 1901.

Hudson, Chuck. Theater in the Georgian Era. The Historical Interpreter. March 16, 2015. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://historicinterpreter.wordpress.com/2015/03/16/theatre-in-georgian-england/

Savage, William. The Forgotten Georgian Origins of Pantomime. Pen and Pension. June 20, 2018. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://penandpension.com/2018/06/20/the-forgotten-georgian-origins-of-pantomime/

Saville, Alice. Pantomime: A Whistlestop History, Through The Eyes of Its Detractors. Exeunt Magazine. December 3, 2015. Accessed November 2, 2022. http://exeuntmagazine.com/features/pantomime-a-whistlestop-history-through-the-eyes-of-its-detractors/

The story of pantomime. V&A. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-story-of-pantomime

Thomanm Laura. The History of Pantomime. Vocalzone. November 16, 2018. Accessed Oct 31, 2022. https://www.vocalzone.com/the-record-blog/music-entertainment/the-history-of-pantomime/

Weighell, Paul. Harlequin and the Pantomime. Penny Plain, Twopence Coloured. Sept 2006. Accessed November 2, 2022. http://pennyplain.blogspot.com/2006/09/from-staff-of-pollocks-toy-museum.html

Watch a modern panto with a lot of traditional flavor here.

Read a scene of Darcy attending a panto here.

If you enjoyed this post you might also enjoy:

Comments

Christmas Pantomime Tradition — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>