Masquerade Balls for the Holidays

The holiday season, particularly between Christmas Day and Twelfth Night was known as a season of fun and frivolity. Balls and parties were high on the list of amusements, and masquerade balls in particular were very popular.

Masked Balls in Regency England

Masked balls were popular in Europe beginning in the fifteenth century. They did not make their way into London, though, until the seventeenth century.

These balls were often held in fashionable establishments and open to the public. In 1810, London masquerade balls were held at the Argyle Rooms, the Opera House, the Pantheon and at Vauxhall Gardens, just to name a few locations. Like public assemblies, anyone who would afford a ticket could attend.

The Times published an advertisements for a masquerades at the Argyll Rooms. Here’s one from 1810:

Masquerade, Argyle Rooms. – By Permission of the Right Hon. the Lord Chamberlain. – S. Slade most respectfully informs the Nobility, Gentry, and his Friends in general, that his BENEFIT MASQUED BALL will take place on Wednesday, the 6th of June. Gentlemens Tickets 1l 11s 6d Ladies Tickets 1l 1s; to include Refreshments, Supper, old Port, Sherry, Madeira, and Claret, to be had at the Office, Little Argyle-street. To prevent the intrusion of improper persons, no ticket will be issued, unless the name and address is left at this Office. (The Times, 5/31/1810)

Masquerades proceeded much like other balls. They usually began late in the evening and lasted into the wee hours of the morning, with attendees returning home after dawn.

Sometimes there were card rooms and gambling, sometimes just dancing and other musical entertainments. Rooms were well-lit and decorated with many flowers. Suppers were served, often featuring cold foods, and always plenty of wine.

Public masks could be very large affairs. A masquerade ball at the London Pantheon in1782 was attended by more than 1500 people!

The biggest difference between these fancy dress balls and ‘regular’ balls, was of course the costumes and the all-important masks. And here in lay the rub.

Anti-Masquerade Sentiments

Like most things that were viewed as fun and very popular (plum pudding, drinking chocolate and novel reading also come to mind,) masquerades had strong, vocal opponents.

Moralists held that the masked events were a threat to English morals. Objections ranged from the foreign influence from Italy and France intruding upon the national pride and morality of England to the ‘lewd and explicit’ nature of the gathering itself. Female attendance in particular was seen as dangerous, threatening honor and delicacy. The presence of cross-dressing participants, seen as the casting off of typical restraints, suggested a throwing away of proper inhibitions as well.

Simply being in costume presented a danger to appropriate femininity. Disguising her true identity could provide a lady with a sense of freedom, leading to her becoming aggressive, domineering and controlling. Dressing as powerful female figures like Greek goddesses could encourage a sense of power and liberty inappropriate to gentlewomen.

Not only did costumes threaten the gender norms of society, they also threatened to blur the lines of social class. A nobleman might be disguised as a beggar, a tradesman as a king. Without the social order to guide interactions, how were people to interact and propriety to be maintained? If status and respect could be won or lost by the change of costume, could not the entire social order be a risk?

Costumes

Perhaps the most common costume at a masquerade was the ‘domino’ which had its origins in Venice. It was not a character perse, but a representation of intrigue, adventure, conspiracy and mystery, the four distinct elements of the atmosphere of the masked ball. Worn by either gender, the costume consisted of a voluminous hooded cloak of silk, satin or brocade, enveloping the body and a mask to cover the face. The domino cloak was usually black, but occasionally white or other colors. The mask was generally white or black, covering the eyes and top of the nose. Sometimes it was held to the face by a wooden rod.

These cloaks and other costumes could be made to order, purchased readymade, or rented from masquerade warehouses. Domino cloaks could be purchased from Warden’s Warehouse in London for as little as 5 shillings, a price accessible by the middle class. Rental prices ranged from 5 shillings to upwards of 2 pounds.

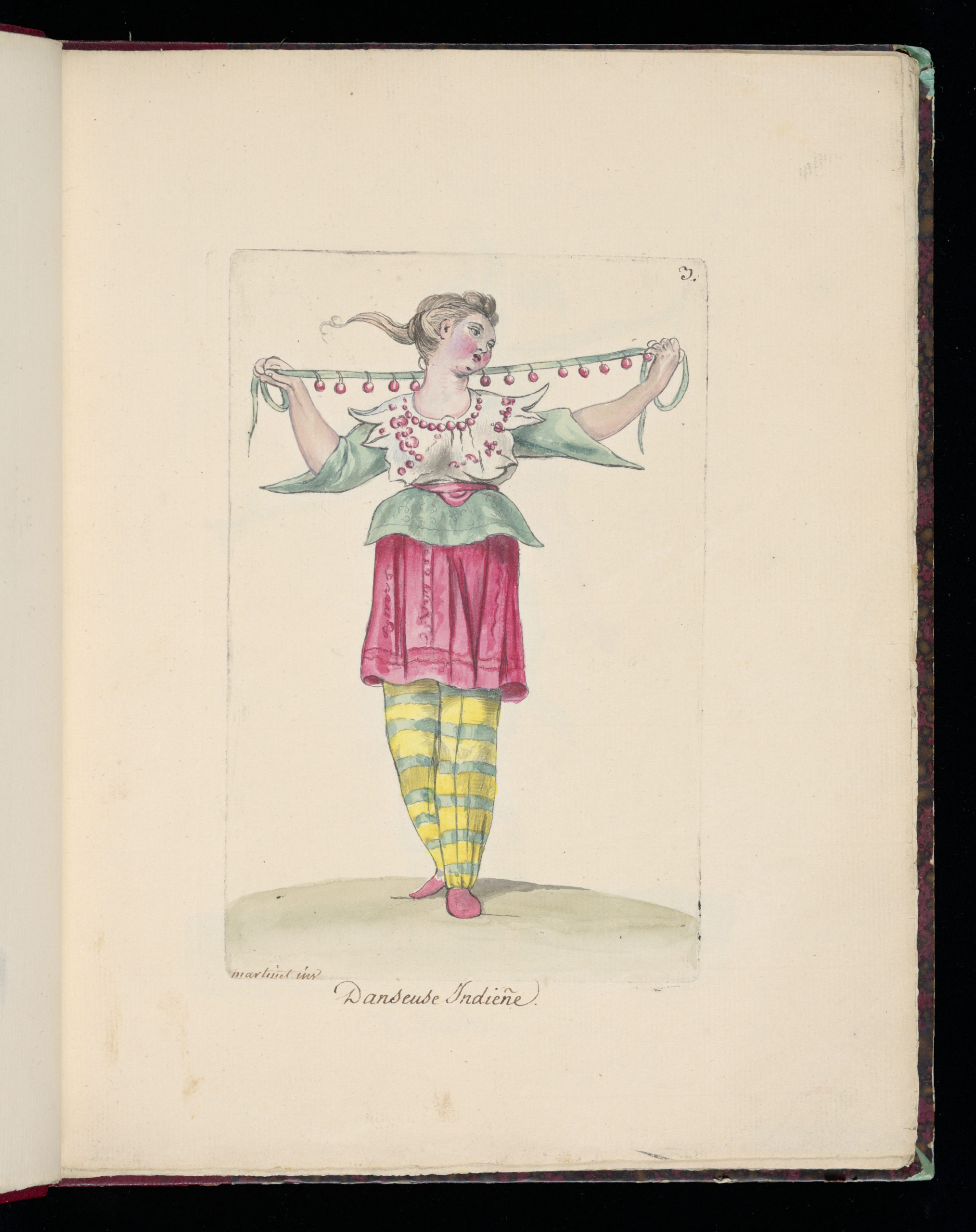

The costumes were often extravagant and frequently played on cultural references of the period. Classical heroes and goddesses of antiquity were popular along with figures from the Italian commedia dell’arte and the Pantomime. More abstract costumes might represent traits such as Virtue or Truth. Ethnic costumes of other nations, or rather imaginative representations of such dress—accuracy was not a priority, gave the event an exotic feel, while figures from folk songs and ballads, and even animal costumes offered as sense of whimsy or fantasy to the event. A shepardess might stand between a sailor and a Roman emperor, dancing with Harlequin, a gypsy and a wild Irishman. The masked ball certainly created a world of its own.

Fashion magazines of the day often included write up and color plates of masquerade costumes.

An Egyptian Costume, July 1807 Le Beau Monde

The head-dress is composed of a rich handkerchief of white lace, which crosses the back part of the head; each corner of the handkerchief, a small distance from the shoulder, falls on the front of the neck; the handkerchief is trimmed round with a magnificent border of peals, and each corner is finished with a bunch of the same; the hair is curled on the top of the forehead with small thick curls, separated with a band of diamonds, which crosses the forehead, and continues round the head; two small curls down the side of the face. A rich white figured sarsnet dress made with a short train, and scalloped back; sleeves very short and covered with a broad flap of white lace; the undersleeve is trimmed round with small French pearls; also the lace, which is fastened to the back part of the sarsnet sleeve with a star of pearls; the front is made full each way, and covered with rich lace fastened in the centre with a star to correspond with the sleeves. An Egyptian train of lilac spider net, showered with pearls, and worked in the centre with a large star of the same, cut in the form of a half handkerchief, wider a one end than at the other; one end is cut square, and gathered up full on the left shoulder with a pearl star; a piece of sarsnet, from under the left arm, richly ornamented, crosses the front, and is fastened with the middle corner of the train to the right knee with a bunch of pearls; the other corner, which reaches to the bottom of the dress, is finished with a large pearl tassel; the dress and train are trimmed round with pearls to correspond. White kid gloves and shoes.

Italian Costumes for Fancy Dress or Masquerade Ackerman’s Repository, 1829

(Left) Costume of the Isle of Procida, Naples. Dress of twilled sarsnet of a bright emerald colour, made high and plain, with a stomacher of gold lace, the skirt terminated by a broad border of scarlet cloth; the pelisse or surtout en militaire of scarlet cloth, lined with white satin and edged with gold lace, the skirt is open in front and reaches only to the border of the under dress; it is turned back, and the corners fastened together behind a gold clasp. The body and sleeves are made close to the shape and ornamented at the seams with gold lace; bands of scarlet edged with gold hang loose from the waist, which is encircled by a gold belt with a splendid clasp in front; epaulettes to correspond; triangular cuffs of Tyrian blue velvet edged with gold; ruffles of the finest lace.

The hair is confined, except a few curls on the temples, by a scarlet and gold checkered silk fazzoletto, tied in front near the top of the head and concealing the corner of a green silk barège fazzoletto, which is edged with gold lace: the opposite corner reaches nearly as low as the waist and is ornamented with a gold tassel; the other corners tie in a knot with long ends under the chin; lace apron, white silk stockings, gold colour satin shoes, pointed on the instep, lilac kid gloves.

(Right) Costume of Ostia, Rome. Camisole of fine lawn made very full, and arranged in perpendicular plaits; the sleeves wide and set in wristbands; stiffened bodice of green cashmere, bordered and trimmed with geranium colour riband, open at the side, and laced with green cord, displaying the camisole beneath. The shoulder-straps are very long bands of geranium colour, and from the centre of each descends a similar band reading to a green cashmere; close upper sleeve, which extends half way between the shoulder and the elbow, and is decorated by a bow of geranium colour riband; the cuff is turned back, and has square corners, ornamented by two rows of riband; geranium colour petticoat of Swiss stuff bordered by two rows of narrow black velvet; apron of white lawn. Hair dressed a la Madonna, entirely concealed by the head-dress, which is formed of a delicate transparent white shawl, enlivened by ends embroidered in rows of the brightest colours, and a deep fringe to correspond. Michael Angelo has beautifully introduced this head-dress frequently in his paintings; the half of the shawl is rolled up and placed on the top of the head, the other half spreading wide over the shoulders, and when the fair wearer chooses, closes in front, and conceals the face; grey stockings, green shoes, with scarlet heels.

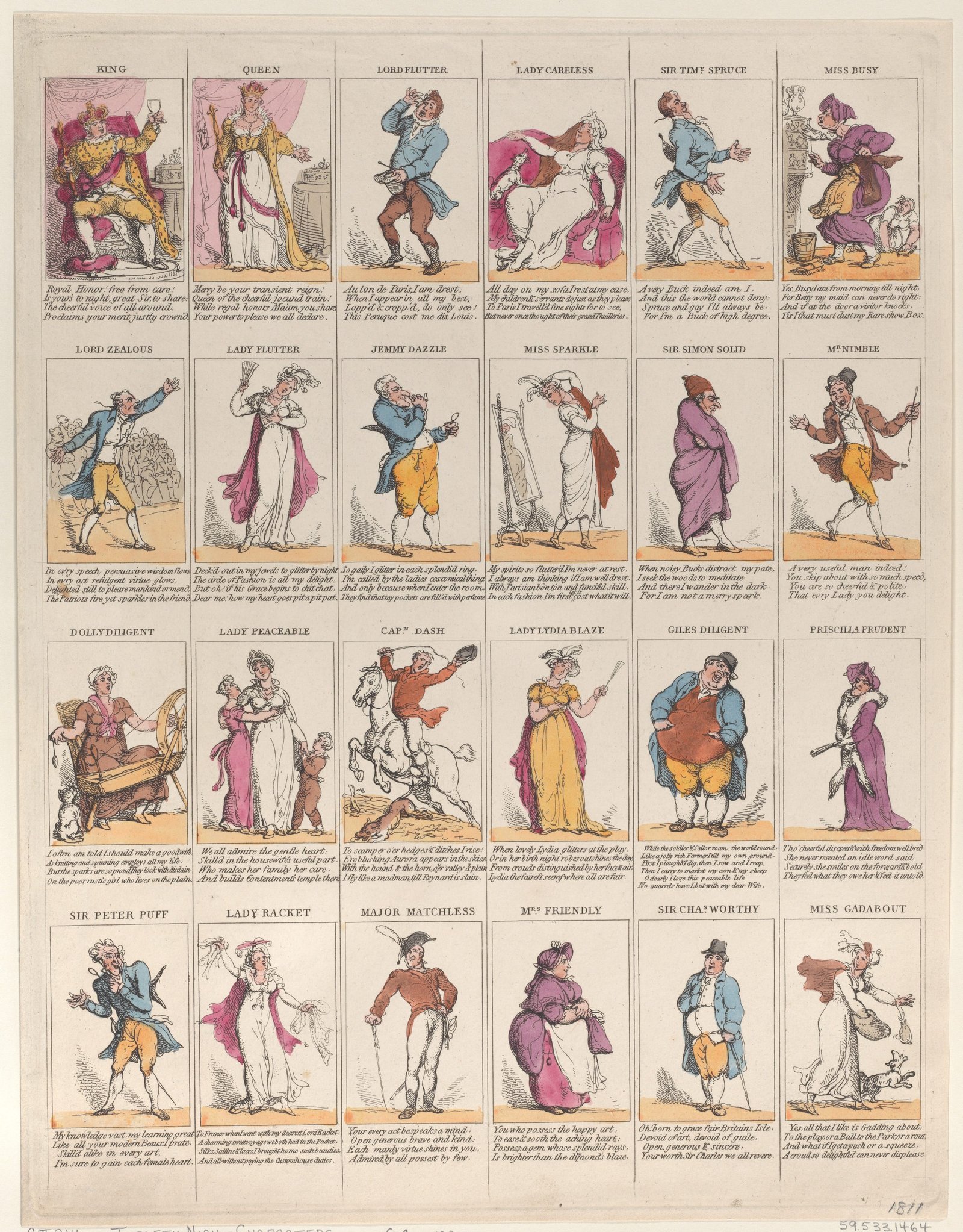

Twelfth Night Characters

Twelfth Night masked balls often involved assigning characters to attendees. Typically, each guest would randomly select a character to play by drawing a slip of paper from a hat or bag upon arrival to the ball. Some hostesses would send characters around to her guests so that they could come already dressed as their character. Others might provide dress up items for their guests to don after characters had been chosen. Guests had to remain in character for the entire evening. If a guest broke out of character during the night they would have to pay a forfeit later.

Besides the King and Queen, a variety of characters, were often pulled from popular literature and plays. Common characters were Sir Gregory Goose, Sir Tumbelly Clumsy, Miss Fanny Fanciful and Mrs. Candour. Sets of pre-made characters could be purchased from stationers, or a family might copy them from books on games and merry-making.

Rachel Revel offered an extensive set of characters in her book as well as instructions that as each character is drawn the conductor of the game arrange them in order of their number and when all the guests have characters, they may each read lines to introduce their character in turn.

Fanny Austen-Knight wrote of set of characters her family enjoyed at a Twelfth Night ball in a letter to Miss Dorothy Clapman February, 1812.

On Twelfth Night we had a delightful evening…about our dress King and Queen, W Morris was King, I was Queen, Papa– Prince Busty Trusty, Mama– Red Riding Hood, Edward– Paddy O’Flaherty, G.– Johnny Bo-peep, H.– Timothy Trip, W.– Moses Abrahams, Eliz.– Mrs O’Flaherty, Ma.– Granny Grump, C– Cupid (by his own desire), Louisa– Princess Busty Trusty, Uncle H.B.– Punch, Aunt H.B.– Poll Mendicant, Jane– Punch’s Wife, Mary– Columbine, Uncle John– Jerry the Milkman, Mrs Morris– Sukey Sweetlips, Sophia– Margery Muttonpie. Soon After, according to a preconstructed plan, some of us retired upstairs to dress Jane as Punch’s wife, in a witches hat, a green petticoat and a scarlet shawl (the remains of our last year’s masquerade) Mrs M.J. and I in beggars clothes to sing carols at the parlour door, and myself in a long scarlet cloak for a royal robe and a wreath of natural primroses (which we had gathered and made up in the morning for whoever would be queen) around my head.

Here’s a gallery of Georgian, Regency and Victorian masquerade costumes for a little more inspiration.

The last costume is a weather vane in case you were wondering. The Last image is Thomas Couture’s “The Supper after the Masked Ball.”

References

Ackermann, Rudolph and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 2 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Ackermann, Rudolph. R. Ackermann’s Repository of Fashions, Containing Elegant Coloured Engravings, with Descriptions of Fashionable Female Costumes, English and French.1829

Beau Monde. July 1807

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Hees, Amy, Ismat Mangla, Steve Porentas, Libby Reece. “The World Upside-Down: Eighteenth Century Masquerades.” University of Michigan. December 8, 2000. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.umich.edu/~ece/student_projects/masquerade/index.html

Hilden, L.A. “Masquerades in England.” L.A. Hilden. March 27, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2020. http://www.lahilden.com/index.php?categoryid=6&p2_articleid=214

Knowles, Rachel. “Masquerade Balls in Regency London.” Regency History. November 6, 2016. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.regencyhistory.net/2018/11/masquerade-balls-in-regency-london.html

Murden , Sarah. “18th Century Masquerade Balls. All Things Georgian. March 19, 2015. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2015/03/19/18th-century-masquerade-balls/

“The Masked Ball.” Jane Austen. June 12, 2011 Accessed November 15, 2020. https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/womens-regency-fashion-articles/the-masked-ball

Revel, Rachel. Winter Evening Pastimes or The Merry Maker’s Companion. 1825.

The Times, 31 May 1810. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/archive/article/1810-05-31/2/1.html

Walton, Gerri. “Masquerade Balls in the =Eighteenth Century.” Geri Walton. October 16, 2013. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.geriwalton.com/masquerade-balls/

This was very interesting – thank you, Maria, – and have a yplendid time, with or without a mask 🙂

Doris

Pingback:Christmas Post Index 2020 ~ Random Bits of Fascination

Sounds a bit chaotic for me. Wow! You have the most interesting posts. I love the pictures that go along with them. They tell a lot. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have a clue what was going on. Again… those in the days of Austen understood what all this meant. We are so far removed from those activities. Blessings, stay safe, and healthy.

There is so much information here I am afraid to admit I just skimmed through it. You are admired in that you do do much research and present it so well. Great work.

Pingback:Advent Calendar Day 15~A Virtual Masquerade Ball and a giveaway! | Jane Austen Variations

Pingback:Christmas Post Index 2021 - Random Bits of Fascination

Pingback:Christmas Post Index 2022 - Random Bits of Fascination