A Gentleman’s Education: the early years

A gentleman’s education set him apart from lesser men, even in his early life. What did that education look like?

In all well-regulated states, the two principal points in view in the education of youth, ought to be, first, to make them good men, good members of the universal society of mankind; and in the next place to frame their minds in such a manner, as to make them most useful to that society to which they more immediately belong; and to shape their talents, in such a way, as will render them most serviceable to the support of that government, under which they were born, and on the strength and vigour of which, the well-being of every individual, in some measure depends., (Sheridan, 1756)

Although sentiments for the education of youth (read here, male youth; female education would not be considered worthwhile yet for quite some time), no one really argued for state provided education for middle and upper class children before 1850. (Brown, 2011) That was left entirely in the hands of the parents. Although considerable effort and activity went into educating these children, it was hardly standardized. How a young boy was educated depended entirely on the preferences and means of his family.

Early education

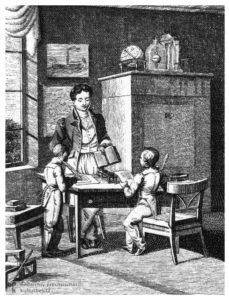

On the whole, early education in the home was preferred. Mothers and governess would provide a boy’s first education, often teaching him the basics of reading and writing. Usually by the age of seven he would graduate from being taught by women to being educated by men. There were no standards of how this worked though. The specific detail of varied by family and by class.

A male tutor might be brought into the home to teach the child, preparing him for the next step in his education. This could continue for just a few years until the boy was deemed ready for a boarding school, or it could continue until he was ready for university study, depending on the education philosophy of the family, usually the father. (Selwyn 2010)

Alternatively, a boy might be sent to a local scholar, often a clergyman, for lessons as a day student. Many clergymen also took such students on as boarders, running small schools to supplement their income teaching anywhere for half a dozen to two dozen students.

Preparatory Schools

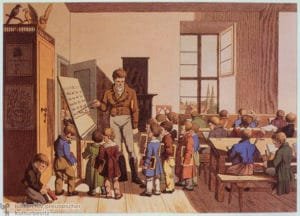

These smaller schools which routinely took boys in the 7 to 13 year old age range were often referred to as preparatory schools, preparing boys for the larger public schools that often preceded entry into the universities.

These schools were usually held in the schoolmaster’s home. Jane Austen’s father, Rev. George Austen conducted such a school out of the vicarage in Steventon beginning in 1793. His living as a vicar was £230 a year. He charged £35 per term for each of his student boarders. It is easy to see how taking even just a few students could substantially augment his family’s income. The work though did not fall on him alone. His wife cooked, cleaned, sewed, and mother-henned the boys in her care, much like a surrogate mother. (Sanborrn, 2016)

In larger schools where the teaching staff consisted of ordained clergymen, teachers could make as much as £200-400 a year, giving them a comfortably middle class income. (Davidoff 2002) Headmasters in such schools, especially if scholars themselves, might enjoy a position of respect and distinction in local society. (Selwyn 2010)

Teachers and Curriculum

By modern standards, preparatory school curriculum was very limited. It consisted mainly of Latin and Greek classical texts (both prose and verse), modern and ancient history, some mathematics, and the use of globes to locate nations. French and Italian might be taught as extras (for additional fees), along with handwriting, dancing, drawing and a smattering scientific subjects. (Le Faye, 2002) No curriculum standards existed, so what might actually be taught varied widely and there was not guarantee that a particular teacher was actually well versed in the subjects he taught.

Teachers in these preparatory schools were most often clergymen or failed ordinals. There were far more men ordained than there were livings to provide for them. In 1805, it was estimated that up to 45% of those ordained never found a church living and were forced to work as (usually highly underpaid) curates for men who had a living, or to try their hand at teaching or take up another occupation entirely outside the church. (Southam, 2005)

After their education in these preparatory schools, boys might then progress to a public school.

Find References HERE

To learn more about Childhood during the Regency era, click HERE

To learn more about Gentlemen during the Regency era, click HERE

To learn more about School during the Regency era, click HERE

To learn more about Education during the Regency era, click HERE

If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy:

This was a very interesting post. Basic education should be the right of every human. Keeping a population ignorant is cruel and inhuman. Education was one of the signs of a gentleman, as only they could afford it. Wickham’s misuse of the gift from his godfather was a waste of money and the opportunity for him to make something of himself. He would have been assured a living for the rest of his life. We see the missed opportunity but are glad he signed it over.

Many JAFF stories embrace the notion that Elizabeth was given the equivalent of a gentlemen’s education by her father. She was raised as the son Bennet never had. She was intelligent, well informed, spoke several languages and helped run the estate as would a firstborn son. This was unusual during this time period as girls were not as well educated as boys. This further exasperated the Mrs. Bennet of mean understanding as she didn’t see the sense in it.

The thing is, even if Elizabeth received unusual levels of education at the hand of Mr. Bennet, she was very unlikely to have learned the classical languages the way a boy would have. The time and discipline alone would not have been likely provided by her parents–Mom need her for other things and Dad wasn’t exactly the disciplined time. Moreover, all the reading of the classics and philosophy tends to create a form of thought that she would not have been exposed to. So, she would have been very well educated for a woman, but that still would not have been a man’s education.

I think that’s really hard for modern readers to grasp.

This is a fascinating post, especially since I’ve invested my life in education, first as a university instructor (adjunct) in literature, writing, and German, and then for 21 years as a home educator. I continue teaching online writing and literature courses for homeschooling families (although some public school families supplement their education with us).

After reading this, I can see how Wickham completely threw away his education; it was an expensive and oh-so-promising gift from Mr. Darcy…especially all the way through Cambridge. Did Wickham ever graduate? I don’t know if that fact is in evidence in P&P except in the fact that he demanded the living from Darcy after accepting compensation for it, so perhaps he did graduate.

I can see how receiving a gentleman’s education would have primed Wickham to believe that he deserved a gentleman’s “leisure,” being quite unaware (or ignoring the fact) that most gentlemen worked very hard at running their estates and making (hopefully) wise investments through their “man of business,” etc. Wickham must have watched both Mr. Darcy senior and then his son work hard at building their estate, but he seemed to think that a gentleman ‘s life was one of gambling and womanizing, which was indeed true of some “gentlemen” but not of the examples immediately under Wickham’s nose.

A wiser man would have used his gentlemen’s education as a tool for his own betterment, as a way to elevate himself above his birth and to indeed pursue the clergy or the law as many a younger son of the nobility would have. But Wickham is more envious than wise, and more lazy than hardworking, and we see how it turned out for him!

Thanks for this interesting post!! Your research is always fascinating!! 😀

Warmly,

Susanne 🙂

It really is interesting what role education plays in the character of Wickham. Throwing it away is a great deal more telling of his character than the modern reader tends to realize.

Pingback:Tutoring in the Regency, by Zoe Burton by Zoe Burton on Austen Authors