The Role of Circulating Libraries

Libraries as a social space

Libraries were first and foremost a business, not a public service as we think of them today. Generally, they required a town with a population of at least two thousand to be profitable. Consequently, they were almost exclusively found in larger towns and resorts.

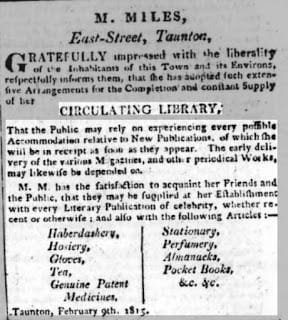

Libraries could exist in smaller areas, but in those places, they were more of a sideline, added to an existing business. “In 1791, William Lane, famed for the Minerva Press, advertised ‘complete CIRCULATING LIBRARIES . . . from One Hundred to Ten Thousand Volumes’ for sale to grocers, tobacconists, picture-framers, haberdashers, and hatters eager for a profitable side line.”(Benson, 1997) Other libraries (those small or not so small) supplemented their income with additional lines of luxury goods like haberdashery, hosiery, hats, tea, tobacco, perfume and even patent medicine. (Erickson, 1990) They might even go so far as to advertise these goods in the local paper.

(McLeod, 2017)

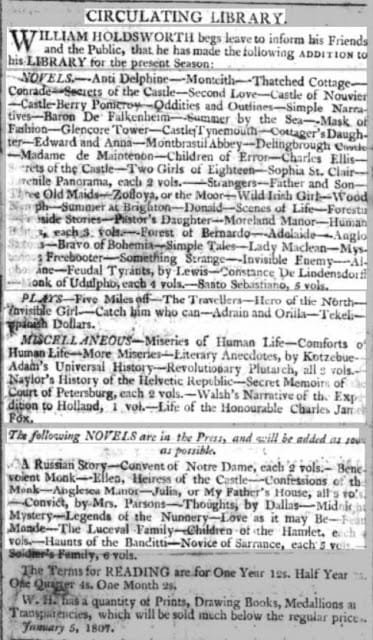

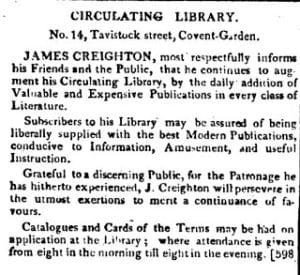

Since libraries survived on traffic from the local public, they sought to draw public attention from the local newspapers. Construction of a new library was often publicized in the newspaper as were additions to a library’s collections.

La Belle Assemblee, the popular ladies’ journal, carried advertisements for circulating libraries: (McLeod, 2017)

To encourage their customers to visit and to linger, libraries, especially in resort areas, often installed reading rooms and “daytime lounges where ladies could see others and be seen, where raffles were held and games were played …” (Erickson, 1990) These rooms were often gathering places for acquaintances to meet or for people to stop and rest during a long excursion into town.

“Since it was the custom to subscribe to the libraries immediately upon arrival in the watering places and resorts, their subscription books became a useful guide to who was in town. In Sanditon the subscription book is used this way. Mr. Parker and Charlotte Heywood go to Mrs. Whitby’s circulating library after dinner to examine the subscription book. When they look into it, Mr. Parker ‘could not but feel that the List was not only without Distinction, but less numerous than he had hoped.’” (Erickson, 1990)

Libraries as a business

The circulating library’s profits (primarily) came from lending books to readers for a fee and later selling the used copies for a reduced price after a book (usually a novel) declined in popularity, typically about nine months after its publication.

Subscription prices varied but were generally affordable for the middling classes. Lending periods could vary depending on the kind of book borrowed—two to six days might be the period for a popular new work. Beyond the price of subscription, heavy fines, which could include purchasing the book, could be imposed for returning books late or damaging the books. (Erickson, 1990)

Just how much did a library subscription cost? “The Nobles’ brothers charged ten shillings sixpence per year, or three shillings per quarter. The subscriber was then entitled to any two books from the collection at any time. For an additional charge they would even deliver books to your London residence… Some libraries, such as Hookham’s, had sliding rates according to services selected.” (Benson, 1997)

Most lending libraries had a reading room with the daily newspapers and the most popular magazines available occasionally. Some had a few bookshelves with the most popular current books on them. What they did not feature were rooms of shelves where patrons could browse. In general, the books were kept in closed stacks, away from the public.

In order to borrow a book, a subscriber would peruse the library catalogue lists and select a title. Then, they would go to a clerk who would consult their lists to find the press mark which would allow them to identify what shelf and position to find the book on. The clerk would retrieve the book and allow the patron to determine whether or not they wanted to borrow said book. Clerks tended to be very knowledgeable on the latest books available and might offer recommendations as well. (Kane, 2015) While waiting for the clerk to retrieve their book, patrons might spend time in the reading room, looking over the goods for sale, or even enjoying some light refreshments.

Library failures

In The Use of Circulating Libraries, Thomas Wilson warned that not one circulating library in twenty is, by its profits enabled to give support to a family, or even pay for the trouble and expense attending it; therefore the bookselling and stationary business should always be annexed, and in country towns, some others may be added, particular small, expensive luxury items. (Erickson, 1990) Though it may seem a rather dire warning, running a circulating library required significant business savvy.

Because novels were largely a consumable good, they had a limited shelf life and depreciated quickly, rather like fruit. A substantial portion of a library’s income had to be reinvested in new stock in order to keep new, attractive titles on their shelves. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, rising book prices made this particular difficult task, with many libraries declaring bankruptcy. Mrs. Martin’s Circulating library in Basingstoke to which Jane Austen subscribed, opened in 1798, and failed in 1800. Half the library failures from 1732 to 1799 took place in the nine year period from 1790 to 1799. (Erickson, 1990)

Over the course of the 19th century, books became less expensive. Declining taxes and falling prices on paper, the rise of the paperback cover, and industrialization made books more affordable. Moreover, public libraries came on the scene and allowed individuals to borrow without a subscription fee. Together, these forces brought about the decline of the circulating library, but their influence on the reading public is still felt today.

Find References HERE

Find the Regency Life Index HERE

Read more about Regency era Amusements HERE.

Read more about libraries HERE.

If you’d like to read more about Regency era history, you might like these:

In Mansfield Park… Fanny helped her sister Susan by getting books for her to read. She used her own money so Susan could have access to books. This was an interesting post. Thanks for sharing your research.

I think Fanny really reflected Austen’s views in that bit of the book. Thanks, JW.