A Country Parson’s Life

I’d like to welcome Brenda Cox today as she shares a fascinating article on a country parson’s life during the regency era.

Painting of Parson Woodforde by his Nephew Samuel Woodforde [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Country clergymen appear in each of Jane Austen’s novels. Some are satirized, like Mr. Collins of Pride and Prejudice and Mr. Elton of Emma. Others are men of integrity, like Edmund Bertram of Mansfield Park and Edward Ferrars of Sense and Sensibility. Austen’s father, two of her brothers, and many of her friends were clergymen, so she knew their lives well.

James Woodforde was another real-life country parson, whose diaries (1758-1802) tell us much about how such men lived. He died when Austen was 27 years old. What was his life like?

Preparation

Parson Woodforde, like Jane Austen’s parson brothers, was the son of a clergyman. Many clergymen followed in their fathers’ footsteps. In Northanger Abbey, Catherine Morland’s father was a clergyman, and was planning to give one of his livings (church positions) to his son when that son was old enough (23).

Like many other clergymen, Woodforde served as a curate, an assistant or substitute minister, for several churches before he received his own living. This gave him some experience in church work. Late in his life, as his health declined, he hired curates to serve his own church, as Dr. Shirley planned to do in Persuasion.

Parson Woodforde studied at Oxford University. Clergymen went to Oxford or Cambridge and followed the same undergraduate curriculum as other men of the upper classes. At Oxford students studied classical literature, Latin, and Greek. Many clergymen stopped with a bachelor’s degree, but Woodforde went on to earn a master’s degree and a Bachelor of Divinity, which means he studied more theological subjects than most clergymen. He held posts at Oxford and eventually received a living from the university. While about half of church livings were assigned by individual landowners, like Lady Catherine de Bourgh of Pride and Prejudice and Colonel Brandon of Sense and Sensibility, hundreds were held by the universities. Woodforde’s living was in Weston Longeville (or Longville) in Norfolk, where he ministered for the rest of his life. (See “Vicars, Curates, and Church Livings.”)

Woodforde was engaged once, but his fiancée married a richer man and Woodforde never married. His niece lived with him for many years, though she found it dull in a small village. Her uncle also had several servants, whose characters he describes; they came and went over the years. In 1776 he paid the local schoolmaster to teach two of his servants to read and write.

Parson Woodforde’s Church at Weston Longville John Salmon [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Church Services

The country parson’s main responsibility was leading church services. Woodforde officiated at a church service each Sunday; he would do a morning service one Sunday and an evening service the next. Services were read from The Book of Common Prayer, a liturgy including Scripture readings and prayers, so leading the service was called “reading prayers.”

The parson preached sermons at these services. Woodforde probably wrote some of his own, but preached others from books of sermons by popular preachers. (Mary Crawford applauds this practice in Mansfield Park.) Clergymen often preached the same sermon multiple times, with minor modifications, and their congregations apparently appreciated the repetition of the same message. Austen’s father preached one sermon thirteen times!

The service for the Lord’s Supper, or Holy Communion, had to be offered at least three times a year. Woodforde generally offered it on Easter (or Good Friday), Christmas, and Whitsunday (Pentecost, the seventh Sunday after Easter), as well as privately to people who requested it or who were dying. On April 7, 1765 Woodforde scolded his clerk (who had certain church duties) for staying up all night drinking the night before Easter and missing “the Holy Sacrament”; the clerk promised never to do it again.

Parsons also read prayers on church holy days. Once when Woodforde forgot St. Luke’s Day, he wrote that he hoped God would forgive him as it was not done on purpose. He also officiated at church services on days the government decreed as days of fasting, for example asking God’s mercy in a war, as well as days of thanksgiving, thanking God for the king’s recovery from an illness, or for a victory in war. (See “A Jane Austen Thanksgiving?” for more.)

Ceremonies

Mr. Collins of Pride and Prejudice expressed his readiness to perform “those rites and ceremonies which are instituted by the Church of England” which Elizabeth Bennet interpreted as “his kind intention of christening, marrying, and burying his parishioners whenever . . . required.” Each of these ceremonies is spelled out in The Book of Common Prayer.

Christening

The parson baptized babies. If a baby seemed in danger of dying, Woodforde went to the home and performed a private baptism, or christening. If there was no need for a home baptism, Woodforde insisted the family bring the baby to church to be christened.

A woman who had a child was “churched” when she returned to church, with another ceremony from The Book of Common Prayer. This was to give thanks that she had survived childbirth; many women, including several of Austen’s sisters-in-law, did not. The parson read a Psalm and prayers of thanksgiving as the woman knelt, and she gave an offering.

Marrying

For weddings, the parson read the “banns” for three Sundays before the wedding to make sure there were no objections to the marriage. (See Courtship and Marriage in Jane Austen’s World for more.) The first wedding Woodforde performed was between an eighty-year-old farmer widower and a seventy-year-old widow! Years later he married a young couple “by License” (meaning they paid a fee rather than have banns) in a “smart genteel Marriage 2 close Carriages with smart Liveries attended.” The sheriff of Norwich and other notables attended. “The Bells rung merry after” (Aug. 28, 1788). Similarly at the end of Northanger Abbey, “Henry and Catherine were married, the bells rang, and everybody smiled.”

Woodforde also had to perform forced marriages. If a man had gotten a woman pregnant, he had to either marry her, support the child, or go to jail. In one case Woodforde wrote that the groom “was a long time before he could be prevailed on to marry her when in the church yard; and at the altar behaved very unbecoming. It is a cruel thing that any Person should be compelled by Law to marry. . . . It is very disagreeable to me to marry such persons” (Jan. 25, 1787).

Burying

The parson of course performed funerals. One morning Woodforde got up at 2 AM to “get or make a sermon” for a farmer’s funeral that evening. He preached the sermon to a church “exceedingly thronged with people” (April 30, 1764). Family members sometimes sent him cakes or gloves after he performed a burial.

Income

The parson’s income came from three sources: tithes, glebe, and fees. Woodforde carefully recorded all his income and expenditures.

Most of the parson’s income came from tithes. Everyone in the parish was required to pay the clergyman a tenth of their farm produce each year. When the tithe was collected, Woodforde hosted a big dinner, “a Frolic,” for those who came to pay. One year he fed them fish, mutton, beef, puddings, and drinks; quite a party!

Woodforde also had “glebe,” a plot of land belonging to the living. He kept cows and poultry, and farmed the land and sold the crops, as his parishioners did, growing barley, peas, hay, clover grass, and turnips. He made his own mead wine from honey and brewed his own beer, which his friends liked very much.

The parson received fees for “christening, marrying, and burying,” but for poor people Woodforde usually returned their payments.

Charity was part of the clergyman’s responsibilities, and Woodforde felt much compassion for the poor. He supervised special collections in times of need. During one very cold winter (1795), 43 pounds and 12 shillings was collected to buy bread and coal for poor families. He also initiated, and contributed to, a collection for a family whose house burned down, and for a widow whose cow died. Parson Woodforde was always concerned for his parishioners and involved in their lives.

Recreation

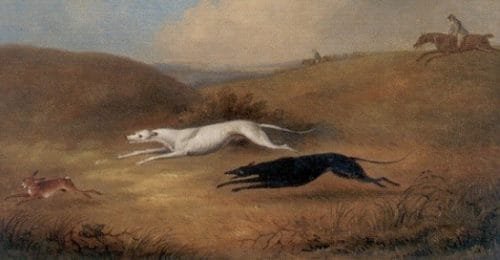

Woodforde Enjoyed Hare Coursing (Hunting with Greyhounds) Dean Wolstenholme the elder [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Woodforde hunted hares with greyhounds (“hare coursing”) and fished; he and his household ate the hares and fish. At home, he enjoyed reading and playing games such as backgammon and card games with small bets. He gave and attended dinners with dancing and music, and went to concerts and plays. Woodforde and his niece took long trips by stagecoach to Bath, London, the seaside at Yarmouth, and elsewhere.

Later in life, Woodforde suffered various illnesses and recorded the home remedies he used for them. On June 27, 1800, he wrote, “I was finely today thank God for it! and this Day I entered my sixtieth Year . . . Accept my thanks O! Almighty God! for thy great Goodness to me in enabling me (after my Late great Illness) to return my grateful thanks for the same.” He lived for two and a half more years, with declining health, until he passed away with the arrival of the New Year in 1803. “Country parson” Woodforde had fulfilled his responsibilities to his people well, and cared for them diligently throughout his life.

References

Austen, Jane. The Complete Works of Jane Austen. Palmera Publishing, 2013. Kindle file.

Book of Common Prayer. London: John Baskerville, 1762. https://books.google.com/books?id=_sYUAAAAQAAJ

Collins, Irene. Jane Austen and the Clergy. London and New York: Hambledon and London, 2002.

White, Laura Mooneyham. Jane Austen’s Anglicanism. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2016.

Woodforde, James. The Diary of a Country Parson 1758-1802. Ed. John Beresford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978.

For more about Woodforde’s church, see http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/westonlongville/westonlongville.htm

Brenda S. Cox is a Christian who has long been a Jane Austen fan. She loves to visit England, where she has explored Austen- and church-related sites in Steventon, Chawton, Alton, Lyme, Winchester, Oxford, Cambridge, Olney, and London, and of course her favorite town, lovely Georgian Bath! She recently completed a fascinating online course in Jane Austen from Oxford University.

Brenda S. Cox is a Christian who has long been a Jane Austen fan. She loves to visit England, where she has explored Austen- and church-related sites in Steventon, Chawton, Alton, Lyme, Winchester, Oxford, Cambridge, Olney, and London, and of course her favorite town, lovely Georgian Bath! She recently completed a fascinating online course in Jane Austen from Oxford University.

In researching the church during Austen’s time, as background for a novel, she found that there was no one source for most of the information she wanted to know, and so began compiling one herself. She’s now working on a book entitled Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also is still working on that novel (a Sense and Sensibility sequel) and, with her background in engineering from Georgia Tech, is researching a book on Science in Jane Austen’s England.

Brenda blogs on “Faith, Science, Joy, . . . and Jane Austen!” at https://brendascox.wordpress.com . Please join her there or on Facebook if you want to know more about faith, or about science, in Jane Austen’s world.

Fascinating post. He was what a real clergy man should be. Caring, kind and considerate. He seems to have led an exemplary life.

I love to read about historical characters like this Thanks, Teresa!

Exactly the sort of clergyman that Mr. Collins and Mr. Elton weren’t, but I could imagine Edmund Bertram and Edward Ferrars being.

Thanks for sharing such an informative article with us.

It’s nice to know there were men like that in real life. Thanks, Anji!

Thank you all for your very kind comments! I apologize that I didn’t see them until now, to respond.

Teresa and Anji, yes, I think Parson Woodforde shows us what a good clergyman of the time was like. I’ve read people who ask, would Edward Ferrars and Edmund Bertram really have been good clergyman? They might not have fulfilled what we hope for today, in being very dynamic preachers or running lots of church programs. But I agree with Anji that they could have been much like Parson Woodforde, quietly doing good in their communities and living with their people and sharing their lives. This was the expectation for a country clergyman, until the Methodists and Evangelicals starting stirring people up with different ideas.

Sooo interesting!! I’m Anglican, so I am familiar with the Book of Common Prayer (BCP). I started out first with the 1662 British BCP which would have been the version used in Regency England as the BCP was not updated until the twentieth century. Since then I’ve used the 1928 BCP as adopted by the Episcopal Church here in the States and helped to edit a new 2011 version of the BCP which reverts to the theology of the original Cranmer 1549 BCP but with updated language and English Standard Version scriptures and references. So I enjoyed hearing so much about the BCP in this post and how it was central to the daily offices of a Regency country vicar. 🙂

A lovely and informative post–thank you, Brenda and Maria!!

Warmly,

Susanne 🙂

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Susanne!

Thanks, Susanne! I’m not Anglican, but because of my study of Austen have been praying daily with the old Book of Common Prayer for some months now. I’ve posted about it a fair bit on my Facebook page and blog ( facebook.com/BrendaSCoxRegency/ and brendascox.wordpress.com), especially during Advent. There are some lovely prayers and inspiring readings. The modernized Book of Common Worship is lovely, too, though sometimes the older language has more richness.

I realized my BCP app wasn’t taking me through the same Bible readings that Austen would have used, so I’ve been reading those since early January; it was quite a lot of reading each day, about 5 Psalms, 2 Old Testament chapters, a chapter from the gospels and a chapter from the epistle. It gives good variety, and it’s also interesting to see what they left out as being too repetitive or too difficult for most people to understand (like the book of Revelation!).

I find that trying new ways of Christian worship enriches my own experience.

I enjoyed this post so much. Thank you!

Thank you Jan!

You’re welcome, Jan! I hope you’ll visit my blog as well, for more on the church in Austen’s England!

Interesting. Can you imagine if the church(es) required 10% of a family’s income today? The Bible does exhort such but I doubt a large percentage would yield to that demand.

Thanks for sharing.

Making it required does rather defeat the spirit of giving, doesn’t it?

Yes, Sheila and Maria, it’s a different outlook than we have today. What’s even harder for us to imagine is that the government was demanding the 10%, to pay to the church. The government and church were considered one (“The Church of England” with the sovereign as head of the church; the bishops and archbishops as members of the House of Lords). This made it quite difficult for the “Dissenters” who believed differently; they were gradually coming into their rights during Austen’s era. I’ve just been writing chapters about this in my upcoming book, and it’s fascinating.

In terms of the tithe itself, I’ve seen people claim that it was justified in that the clergyman provided many services to the community (such as visiting and doctoring the sick, counseling, holding money for people), so it was fair that they should all pay, even those who didn’t go to church. However, as more and more people became non-Anglicans–by 1851 it was almost half–resistance against the mandatory tithe increased until it was abolished.

Thanks for sharing this article. It was fascinating.

What a kind and godly man Rev. Woodforde was. A great example of a good Christian life.

Thanks, Angelia! I’m so glad you enjoyed it.

Pingback:A Jane Austen Thanksgiving? – Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen

You say “The parson’s income came from three sources: tithes, glebe, and fees …” What about the living if he was the vicar, or the salary if he was a curate?

Pingback:Joy to the World: Psalms, Hymns, and Christmas Carols in Jane Austen’s England – Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen