Camp followers in the long Georgian era

I’d like to welcome Jude Knight today as she shares a fascinating article on the role of camp followers during the the Georgian and regency era.

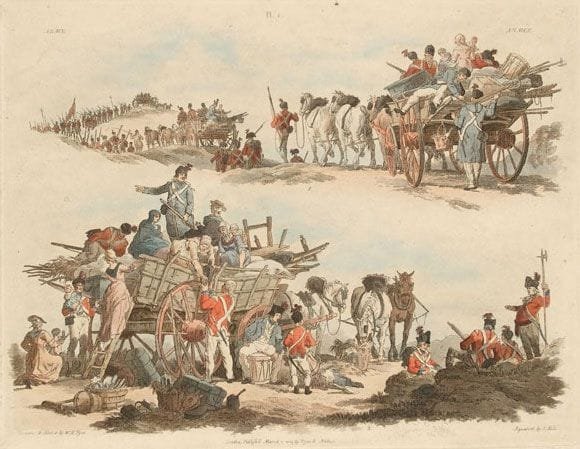

To our modern minds, it seems strange to think of civilians, including women and children, travelling into combat zones. Yet until the second half of the nineteenth century, civilians were an essential part of how armies worked. Collectively, anyone who followed the army that was not a soldier was called a camp follower. And every army had all kinds of followers.

The commissariat managed the supply chain

The commissariat managed the supply chain

First, the commissariat. This was a uniformed civilian service, funded by the Treasury and in charge of all non-military supplies, including food for army rations.

The officers of the commissariat arrived at any war with the advance guard, as they did in the Peninsular War of 1807 to 1814. Their job was to roam the countryside, searching for supplies and for a place to store them. It can’t have been a risk free operation!

Once established, a depot needed a storekeeper, and supplies needed to be brought for storage, so the commissariat had many employees and a budget for hiring or buying mules and carts. With these resources, the commissariat often had a role in storing and distributing military supplies, as well as non-military.

Other civilian services lacked the central organisation of the commissariat. Some were semi-official, authorised by the local commander, drawing army rations, and provided with transport when the army moved. Some were unsanctioned or even illicit.

Tinker, tailor, beggar-man, thief

Sutlers negotiated with locals and sold goods that were not supplied by the commissariat: tobacco, coffee, sugar, and other supplies. A sutler was usually authorised at brigade level, and the role in each brigade often went to the wife of one of the soldiers.

Saddlers, tailors, shoemakers, and farriers might be soldiers (if someone with the right skills could be found) or civilians, but they were all essential to the operation of the army.

So were medical staff. The Army Medical Department employed around one surgeon for every 250 soldiers. Military surgeons were not commissioned into the army, so were technically civilians, but they were on the payroll. They were assisted by soldiers with more or less medical training, gained on the job, and by camp followers, usually wives of soldiers.

Wives and families on the march

Wives and families formed the largest group of camp followers. In England, soldiers’ families lived around the barracks, as military families do today. When the regiment travelled overseas, regulations stated how many wives they’d take with them (one for every six soldiers was common). To be in the ballot, a woman had to be a wife of good reputation. Mostly, women with children were excluded. On long overseas postings, babies arrived anyway, often on the march or even during battles.

Those not selected could seldom afford to follow their menfolk. They stayed in England and survived the best they could, often in a garrison city far from family, lacking work opportunities and not recognised as part of the local parish for poor relief.

Those selected faced hard work and unknown risks, but—though they might not be an official part of the army—they were on the books. Yes, they had to have an officer’s approval to follow the army and they were subject to military discipline, but they received rations (a half ration for a wife and a quarter ration for a child) and they were paid for the work they did.

Wives were not only sutlers and nurses. They were also responsible for many other important jobs that kept the army operating: laundering clothes, cooking food, sewing and mending, watching the baggage, looking after sheep and cattle (food on the hoof), and acting as servants to officers and their families.

And, of course, they provided sexual services to their husbands. The rest of the soldiers in the unit would have to make other arrangements or go without. Wives who followed the army were, as I said before, women of good reputation.

War brides and their particular problem s

s

Local women filled the gap, either on a temporary basis, as prostitutes, or longer term as mistresses or even wives. Locally acquired wives and families provided the same wide range of services as those brought overseas with the regiment, but the army didn’t hold itself accountable for transporting women and their children to England when the war was over, or when the soldier died, unless the woman could produce proof of a legal marriage, recognised by the Church of England.

…the return home meant a voyage by sea, this being something that for many of the women concerned constituted an insuperable obstacle. Thus, the authorities for the most part would only meet the cost of the journey in the case of women who were legally married, which most of the Spanish and Portuguese women were not. When the British army took ship at Bourdeaux in the wake of the fall of Napoleon, then, several hundred women found that they were to be left behind. Shocked by the news, a number of regiments appear to have raised subscriptions to help the women, the vast majority of whom were absolutely destitute, whilst a few men deserted rather than forsake their partners, but in general there was nothing to be done, the embarkation was going ahead amidst scenes of the utmost despair, the camp followers concerned eventually being sent back across the Pyrenees in the company of a brigade of Portuguese infantry.

What the future held for the 950 women concerned does not bear thinking about. Many had probably never been forgiven by their families for running off with British soldiers, while others had no homes to return to. A handful, perhaps, managed to find husbands in their wanderings, but the fact that few could have provided even the humblest of dowries could not but have told against them. Sadly, then, we may assume that, faut de mieux, many ended up as common prostitutes, and all the more so as the fact that had run off with foreign soldiers without contracting the bonds of marriage almost certainly precluded them from obtaining any of the limited compensation that was available from the state (in so far as this was concerned, in Spain, at least, it was decreed, first that pensions should be paid to the widows of men killed in the war, and, second, that girls who had been orphaned in the conflict should be provided with dowries; in practice, however, little money was actually paid out, in the first place because the Spanish state was all but bankrupt, and, in the second, because the countless women of whose husbands there was no trace had no means of proving that they were actually dead). (Women in the Peninsular War by Charles J. Esdaile (2014) pp. 219-220)

Jude Knight’s writing goal is to transport readers to another time, another place, where they can enjoy adventure and romance, thrill to trials and challenges, uncover secrets and solve mysteries, delight in a happy ending, and return from their virtual holiday refreshed and ready for anything.

She writes historical novels, novellas, and short stories, mostly set in the early 19th Century. She writes strong determined heroines, heroes who can appreciate a clever capable woman, villains you’ll love to loathe, and all with a leavening of humour.

Website ~Facebook:~Twitter~Pinterest:

About her latest book: A Raging Madness:

Their marriage is a fiction. Their enemies are all too real.

Ella survived an abusive and philandering husband, in-laws who hate her, and public scorn. But she’s not sure she will survive love. It is too late to guard her heart from the man forced to pretend he has married such a disreputable widow, but at least she will not burden him with feelings he can never return.

Alex understands his supposed wife never wishes to remarry. And if she had chosen to wed, it would not have been to him. He should have wooed her when he was whole, when he could have had her love, not her pity. But it is too late now. She looks at him and sees a broken man. Perhaps she will learn to bear him.

In their masquerade of a marriage, Ella and Alex soon discover they are more well-matched than they expected. But then the couple’s blossoming trust is ripped apart by a malicious enemy. Two lost souls must together face the demons of their past to save their lives and give their love a future.

s

s

I am, again, so glad to have been born in modern times, where we have welfare and Medicaid in the USA for any who are destitute. Of course, we don’t have “camp followers” going to Afghanistan or other war zones, but in the states there are towns built around forts and other military establishments. I lived in Killeen, Texas when my husband was stationed at Ft. Hood. But there are many around the world who are destitute for other reasons.

Reading this account is rather depressing even though it is part of history. Thanks for sharing this research.

The book seems to be akin to stories of marriages of convenience but herein there was no marriage – just an arrangement.