The 19th Century British Post

Guest post by Wendi Sotis.

In 1784, the British postal system was reformed by John Palmer, a theatre owner in Bath, who had found a way to transport actors at high speeds and applied it to the mail. With the introduction of mail coaches, security increased dramatically over that of employing post boys, who often conspired with robbers to arrange thefts.

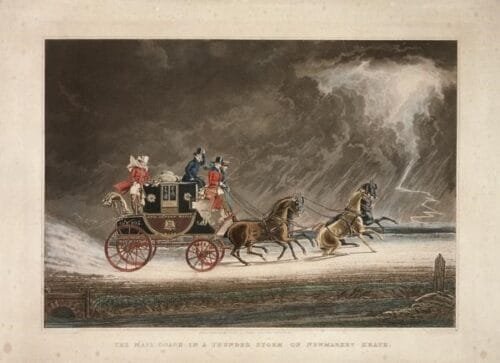

By 1811, more than two hundred mail coaches ran regular deliveries on “post roads.” The coaches were painted black with red wheels; the doors and bottom panels were maroon and sported the Royal Coat of Arms. Light and fast, they eventually carried four passengers inside and three outside – none of which were allowed anywhere near the Mail Guard who stood at the back above the coach, facing forward.

Not only were Mail Guards well paid, but they were granted sick leave and pensions as well to avoid the corruption seen in the past with post boys. Tips were expected from passengers travelling by the coach—a shilling a passenger was expected for a lengthy trip. Wearing the uniform of the Royal Guard, their scarlet coats with blue lapels and gold trim were hard to miss. They were equipped with two pistols, a blunderbuss, and a timepiece in order to keep records of the coachman’s progress. Mail coaches did not pay tolls; the Guard would blow a special horn when approaching a tollgate, and if the toll keeper did not raise the gate in a timely manner, he would have to pay a hefty fine. There were horn signals for several events, including a warning to other coaches to make way, that the mail coach was about to make a turn, and serving as advance notice to a post office that the coach would soon approach.

Postmasters were private business owners, usually innkeepers who were permitted to make extra money by charging a fee to deliver mail to non-post office villages and estates. As the coach passed through towns and villages that were not scheduled stops, the guard would throw out bags of incoming mail while grabbing bags of outgoing mail from the Letter Keeper or Postmaster.

Travelling by a mail coach was faster than by other methods, but the trip could be uncomfortable for passengers. They stopped only for post office business, such as changing horses, and not for meals or any other “convenience.” Travelers were expected to walk up steep hills to spare the horses the strain of pulling their weight.

Private post services were slow and unreliable, but cost less than the Royal Mail. If someone wished a letter to be sent more quickly than the regular post, an express was sent through the post office. A private servant could also carry a letter, but their master would have to pay all fees associated with their ride, including meals and changes of horses. Since the post had become so reliable, many did not use express service.

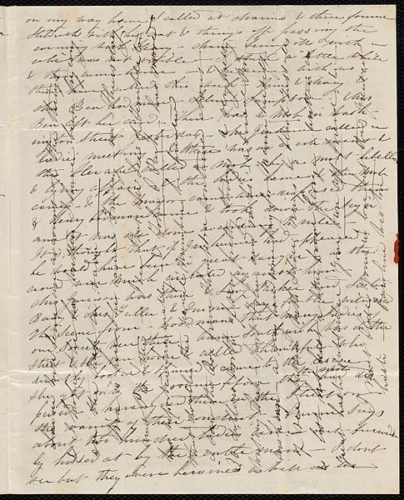

Before 1840, stamps as we know them today did not exist. Fees could be paid in advance in some cases, such as London’s Penny Post, but it was an accepted practice that the recipient would pay. Since the cost was determined by the number of pages used as well as by the mile, to save money, many would write down the page and then turn the paper sideways and “cross”, writing between the words. Re-crossing would be when the person wrote diagonally as well, but the letter would be very difficult to read.

“Franking” was free mail usually limited to members of Parliament and officials, though the practice of gifting blank franked pages to friends became a problem. The Clerk of the Roads franked newspapers. Members of the military were granted a reduced mail rate beginning in 1795.

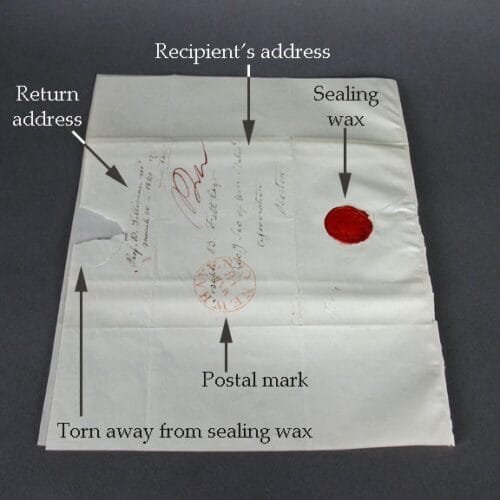

There were no envelopes – the outside of the page would be intentionally left blank with only the address and return direction written there. The page was folded in such a way that would keep the writing on the inside and the ends tucked together. Some used wax seals to hold the letter together.

Based on the mileage from The Regency Encyclopedia’s Map Gallery, assuming they were one-sheet, the letters that Elizabeth Bennet sent from Rosings to Jane at the Gardiner’s house in London cost Mr. Gardiner six shillings. Mr. Bennet would have had to hand over ten shillings to the Postmaster in Meryton to receive a letter from his favorite daughter, Mrs. Elizabeth Darcy of Pemberley.

References:

Mail coach, Public Domain Photo, “Mailcoach”, WikiMedia commons, Web, 31, October, 2006

Crossed Letter, Public Domain Photo, “From Caroline Weston to Deborah Weston; Friday, March 3, 1837”, WikiMedia Commons, Web, 8 July 2010

How to Post a Letter, 19th Century Style, Iowa State University Library Preservation Department, Web, 14 Feb. 2011

British Postal Museum & Archive

J. C. Hemmeon, PhD. The History of The British Post Office. Harvard Economics Studies, Published under the direction of the Department of Economics Vol VII, From the Income of the William H. Baldwin, Jr., 1885, Fund, Cambridge Harvard University. 1912

The Regency Encyclopedia – Map Gallery

Fascinating post, thanks for sharing!

Blog and Facebook follower

Felicia

Pingback:The 19th Century British Post | Wendi Sotis, Author

Ótimo post!Obrigada por postar!

Até o próximo!!

I wonder if things are any faster today? I suspect not – but there again perhaps I’m just being cynical.

A very interesting post, thank you.

Grace x

Wow, Wendi, what a great, informative post. Thank you for the visual–it really helps to see that!!

Oooh, pick me, I have a copy but I want to win one for my sister!

There seems to be a conspiracy to tell us that Mail guards were “well paid.” They were only paid 10 shillings and sixpence a week compared to the coachman’s usual guinea (21 shillings). An agricultural labourer could earn more than a guard (http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~alan/family/N-Money.html). The security of a pension and paid leave were however desirable extras.

Both guards and coachman made their extra money from “perquisites” at the end of their ground, extracted with charm and/or persistence from each passenger – a mere shilling was looked at with some scorn, and the guard/coachman might sarcastically return a tip if it was as small as sixpence, implying that the donor needed it more than he did. So in a day’s work the guard might make half his week’s wage from “perks.” They took home a good amount – but it wasn’t what they were “paid” by the Post Office.

The image of “The mail coach in a thunderstorm on Newmarket Heath, Suffolk,” is from 1827, and the artist is G Reeves.

I like facebook page and follow blog

I love learning about the little things about history especially when in the 19th century.

This is really interesting! I like learning things like this. It all seems a little complicated! But maybe it’s just been a long day lol. I tend to be wordy so I’d have to write reeeally small and cross my pages so the recipients wouldn’t have to pay an arm and a leg.

Thank you for the giveaway! I follow the blog via email and subscribe to the newsletter.

“Mr. Bennet would have had to hand over ten shillings to the Postmaster in Meryton to receive a letter from his favorite daughter, Mrs. Elizabeth Darcy of Pemberley.”

Wow, that’s expensive! Ten shillings is about fifty or sixty dollars in today’s money. No wonder folks wrote letters across to squeeze in more words per sheet. Thank you for the information!

Hi! Thanks, everybody, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Sue, that’s great information, thank you for your additions.

Good luck everyone!

thanks, Wendi, for the great info! your giveaway generosity def appreciated .. 🙂

the illlustration of the post in that weather speaks volumes!

loved to hear the background of the innovator from Bath! certainly timed well with the final day of the JA Festival =)

Royal Mail from UK still arrives faster than US or Cdn post !

Good luck! Did you go to the Festival?

a newsletter subscriber – TY Maria !

also rcv your Daily Digest – MUCH appreciated =)

and you have been well ‘liked’ by me on FB !

Thank you, Maria Grace, for hosting the giveaway!

Soundas interesting. I’ve read tid bits here and there about the post in historical settings but this was by far the most informitive. Lovely post and I would love to be entered for the giveaway (Canada e book)

-liked on fb

Margaret

singitm(at)hotmail(dot)com

Pingback:Giveaway Winners « Maria Grace

Pingback:What Rowland Hill really meant « cartesian product

Pingback:When Paper was a Luxury - Random Bits of Fascination