I was delighted to be invited to offer Random Bits of Fascination part of my talk on Travel in Jane Austen’s time. My research came about through my own curiosity of the modes of transport Jane Austen gave her characters in the novels.

Transport in Jane Austen’s time mostly revolved around one’s own two legs or the four legs of a horse or donkey. Sedan chairs were still in use but were much less popular although there is documentation that Jane Austen did use one in Winchester during her final illness.

Horse ownership was expensive. A good carriage horse could cost £100, a riding horse or a cob could cost between £25 and £40, depending on the age, health and appearance of the animal and keeping one for a year could cost more than keeping a servant. The cost of keeping a single riding horse in London could be around £120 a year. Carriages were made to order and a family coach could cost £400. You definitely had to have a certain level of wealth to consider horse and conveyance ownership.

The most economical alternative to horse ownership was a donkey. While living at Chawton Cottage on a little less than £500 a year, Jane Austen, her sister Cassandra, and their mother had a donkey and cart. Jane’s niece Anna Lefroy also owned a donkey carriage as her aunt recommended, in a letter, the use of it during a pregnancy.

The most economical alternative to horse ownership was a donkey. While living at Chawton Cottage on a little less than £500 a year, Jane Austen, her sister Cassandra, and their mother had a donkey and cart. Jane’s niece Anna Lefroy also owned a donkey carriage as her aunt recommended, in a letter, the use of it during a pregnancy.

The advantage with donkeys were that they were cheap to keep but they were slow and couldn’t carry too much. In Emma, when Mrs. Elton’s carriage horse is lamed she wishes for a donkey to take her to Box Hill, “with my caro sposo walking by.”

Taxed Cart

Jane Austen also mentions in her letters the tax cart or more correctly called a taxed cart. The Oxford English Dictionary defines this as ‘a two wheeled (originally springless) open cart drawn by one horse, and used mainly for trade or agricultural purposes, on which was charged only a reduced duty (in 1795 the annual sum of ten shillings). This afterwards was taken off entirely)’. It was a very basic form of transport used by many as it was relatively cheap to run.

In a letter to Cassandra Austen on Sunday 24th January 1813, Jane Austen is quoted “…In consequence of a civil note that morning from Mrs Clement, I went with her & her Husband in their Tax-cart; – civility on both sides; I would rather have walked, & no doubt, they must have wished I had.”

People without their own transport had to rely on public transport, particularly the Mail Coaches or the Stagecoaches. The Royal Mail coaches were the cause of improvements to the English mail service. Mails from London to Edinburgh often arrived within five minutes of their scheduled time. Royal Mail trips cost about a penny per mile more than stagecoaches and required travelling at night, but their reliability and safety made them popular.

The Royal Mail

Royal Mail coaches carried letters and passengers and established a tradition of excellence in speed and reliability. The first was on August 2nd 1784 from Bristol to London via Bath overnight and took 16 hours. Horses were changed on average every ten miles and this change could be achieved in a startling two to three minutes! The coach was slung on springs very high so that the motion was often intolerable. The landlady of the New London Inn, Exeter, was unhappy that the passengers arriving there in the mails were generally so ill that they went at once to bed without ordering any supper, which was not to the advantage of her inn.

We know that brother Henry returned from Steventon to London overnight by the mail in early January 1800, which must have been a chilly ride and another brother, Frank, intended to use a similar overnight mail to travel from Southampton to Kent.

In Mansfield Park, Edmund Bertram travelled to Portsmouth by the mail to collect Fanny Price and Henry Crawford’s offer of a place in his carriage for a journey to London saved William Price a trip by the mail.

The Stage Coach

Stage coaches were so called as they carried travellers between ’stages’, usually coaching inns. A stagecoach was a type of covered coach used to carry passengers and goods inside. Cheaper seats could be had on top of the coach but if you fell asleep you would “drop off” and more often than not the coach would not stop for you; hence the old adage for falling asleep!

It was a strongly sprung carriage and generally drawn by four horses, usually four-in-hand, that is, four horses driven by one driver. Extra horses cold be provided for steep hills and passengers could be asked to walk at these times to ease the burden!

Fresh teams of horses were kept in readiness for the timetabled arrivals and private patrons could hire animals too. Some inns could offer stabling for up to 300 horses. The inns would also provide meals for the passengers but some were famous for their slow service, only producing the fare just as the call to leave was made. Innkeepers could then use the same joint of meet for many coach loads of travellers!

Only a few of Jane Austen’s characters used stagecoaches. Robert Martin returned from London by stagecoach with news about his engagement to Harriet Smith. Also in Emma, Mr. Elton used stagecoaches to go to Bath, and delightfully returns with the wonderfully ridiculous Mrs Elton. In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs Jennings is happy to send her maid, Betty, to London by coach to allow room for the sisters Dashwood to travel with her to her home in Portman Square. In Mansfield Park, nine year old Fanny Price made her way from Portsmouth to London by public coach, to be met by the Bertram nanny.

Jane’s letters show that she used stagecoaches occasionally to carry her trunk, and she travelled in them now and then in her later life. Earlier, at the age of 20, she wrote thus to her sister about a proposed trip to London: “As to the mode of our travelling to Town, I want to go in a Stage Coach, but Frank will not let me.” It was fine for Frank to travel by coach but definitely not his sister!

The Chaise

The chaise was a small closed carriage more popular for travelling rather than recreation. They could carry differing numbers of people, with seats for one or two, with a side seat that could pull out to hold three. Sometimes there were two seats, both facing forward, so that it could hold four. They were very common on the road and included the hack post-chaises that could be hired, travelling on the post-roads that had spread all over England by Jane Austen’s time. The horses of a chaise were not controlled by a driver seated on the box on the vehicle, but by a post-boy, or postillions, who rode the near, or left, horse. On a large chaise four horses were used, often with postillions on one or both lead horses in addition to the near wheel horse.

There a quite a few chaises mentioned in the novels. In Sense and Sensibility Mrs. Jennings used her chaise to take herself and Elinor and Marianne Dashwood from Barton to London and from London to Cleveland (hence poor Betty travelling by coach!) and Mr. and Mrs. Robert Ferrars travelled from London to Dawlish in a chaise after their marriage. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Bingley owned a chaise-and-four and Elizabeth Bennet travelled to Hunsford with Sir William and Maria Lucas in the same type of vehicle. Lady Catherine famously arrives at Longbourn to harangue Elizabeth in a chaise and four. “… they perceived a chaise-and-four driving up the lawn. It was too early in the morning for visitors, and besides, the equipage did not answer to that of any of their neighbours. The horses were post; and neither the carriage nor the livery of the servant who preceded it were familiar to them.”

Lady Bertram and Mr Rushworth owned chaises in Mansfield Park and in Emma, Frank Churchill hires one from the Crown but the Sucklings, of course, own one chaise. In Persuasion, we are only aware of Sir Walter Elliot owning a chaise, however we also know that Anne Elliot made an uncomfortable ride from Lyme to Uppercross with Captain Wentworth following Louisa Musgrove’s accident on The Cobb in a chaise and four hired from the local inn. A further chaise was hired from Crewkerne to return Charles Musgrove to Lyme with the family’s old nursery-maid, to care for Louisa.

When General Tilney and his party set off from Bath for Northanger Abbey it Austen tells us, “the fashionable chaise-and-four-postillions handsomely liveried, rising so regularly in their stirrups, and numerous out-riders properly mounted”. However, poor Catherine Morland was forced to use post-chaises and post-horses for her trip from Northanger Abbey to her home in Fullerton when ejected by the General! It was shocking for a young gentlewoman to be travelling post like this so Austen is able to emphasise the Colonel’s anger with her.

We are told that she stopped “only to change horses”. This must mean that she did not stop for meals or rest, because Mrs. Morland’s remark of “now you must have been forced to have your wits about you, with so much changing of chaises and so forth . . .”) shows that she changed vehicles too. Since Catherine’s 70 mile trip took “about 11 hours,” she averaged a little more than 6 miles an hour.

In May 1801 we know that Jane herself travelled from Devises to Bath in a chaise. She tells us in a letter to Cassandra, “We had a very neat chaise from Devizes; it looked almost as well as a gentleman’s, at least as a very shabby gentleman’s; in spite of this advantage, however, we were above three hours coming from thence to Paragon, and it was half after seven by your clocks before we entered the house.”

In 1813 two post-chaises were hired to add to Edward Knight’s coach to take the family from Chawton to Godmersham. Five travelled in the coach, eight in the two chaises, a chair carried another two and yet two more rode on horseback! Quite the expedition!

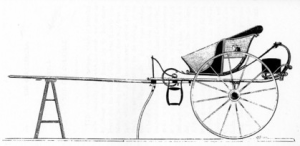

The Curricle

The curricle was another popular vehicle, a kind of early sports car for boy racers!

It was a light two-wheeled carriage, sometimes open but often with a top that could be lowered, and it was usually drawn by two horses. Willoughby shockingly drove Marianne in his curricle all over the neighbourhood of Barton.

Henry Tilney, driving Catherine from Petty-France to Northanger in his curricle, made her “as happy a being as ever existed.” All the curricle owners were young men: Mr. Darcy, Mr. Walter Elliot, Charles Musgrove, Henry Tilney, John Willoughby, and Mr. Rushworth.

Henry Austen must have owned a curricle as Jane Austen, when staying at Sloane Street stated in a letter dated 20th May 1813, that “we had no rain of any consequence; the head of the curricle was put half up three or four times.”

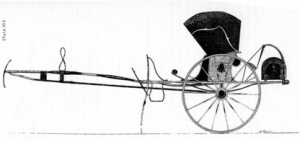

The Gig

A gig was similar to a curricle. Sometimes the names seem interchangeable, and a carriage-builder of the time, in a treatise on carriages, captioned this drawing “Gig Curricle.” The biggest difference between the two was that a curricle was normally pulled by two horses and a gig by just one, thus making it much more sedate with less speed and obviously less dashing. Only requiring one horse also makes it cheaper to keep.

A gig was similar to a curricle. Sometimes the names seem interchangeable, and a carriage-builder of the time, in a treatise on carriages, captioned this drawing “Gig Curricle.” The biggest difference between the two was that a curricle was normally pulled by two horses and a gig by just one, thus making it much more sedate with less speed and obviously less dashing. Only requiring one horse also makes it cheaper to keep.

Admiral and Mrs. Croft acquired a gig while at Kellynch Hall, and we know it could just accommodate three people as the Crofts were able to give Anne Elliot a ride to Uppercross in Persuasion.

John Thorpe, Mr. Collins, and Sir Edward Denham also owned gigs, and so did Jane Austen’s brother Henry. She mentions in a letter dated the 6 June 1811 to Cassandra “He travels in his gig, and should the weather be tolerable, I think you must have a delightful journey.” It is interesting that Jane Austen gave gigs to both John Thorpe and Mr Collins. It allowed her to maintain the disparity between these characters and those of Henry Tilney and Fitzwilliam Darcy with their superior sports cars. However it is also interesting that John Thorpe boasts to Catherine Morland, that his gig was ‘curricle hung’!

Henry Austen also had a gig. Jane Austen mentions in a letter dated the 6th June 1811 to Cassandra “He travels in his gig, and should the weather be tolerable, I think you must have a delightful journey.” It appears that Henry was not content to own a gig as we have already seen that by 1813 he was the owner of a curricle!

The Chair

The chair was smaller and lighter vehicle. It was also sometimes called a whiskey. It did not have a top, was pulled by one horse, and usually used just for recreation. A chair appears only in The Watsons, where it was owned by the Watson family, probably because it was cheaper than many other carriages. Jane Austen’s brother James owned a chair, showing his lower income as a cleric. His chair, according to a letter of 7th January 1807, appears to have been pulled by a horse named Ajax.

The Coach

Coach was a name generally given to large conveyances, but there was a vehicle known as a coach. Large families like the Bennets and the Musgroves, owned coaches, large vehicles which regularly held four to six passengers and on occasion even more. They were used for travelling large distances and would have looked similar to the mail and stage coaches. We have also heard that brother Edward had a coach that held five.

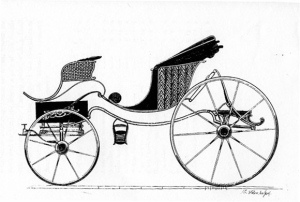

The Phaeton

Phaetons were another class of light vehicles. They were generally used for recreational drives rather than travelling long distances. There were very many styles of phaeton with either no top at all or one that could be put back when the weather was good enough to enjoy being seen! Mrs. Gardiner suggested that she and Elizabeth use a “low phaeton” for riding around the park at Pemberley. There were also high phaetons where the passengers were perched very high indeed. In Jane Austen’s novels only Miss De Bourgh actually owned a phaeton. Jane Austen mentions in a letter from Bath in May 1801 that she would like to go out in Mr Evelyn’s phaeton.

Phaetons were another class of light vehicles. They were generally used for recreational drives rather than travelling long distances. There were very many styles of phaeton with either no top at all or one that could be put back when the weather was good enough to enjoy being seen! Mrs. Gardiner suggested that she and Elizabeth use a “low phaeton” for riding around the park at Pemberley. There were also high phaetons where the passengers were perched very high indeed. In Jane Austen’s novels only Miss De Bourgh actually owned a phaeton. Jane Austen mentions in a letter from Bath in May 1801 that she would like to go out in Mr Evelyn’s phaeton.

The Chariot

The chariot was another light vehicle. This was drawn by four horses and had a more unusual seating arrangement for the time, carrying four people on two seats facing forward, not facing each other. It looked a bit like a large post-chaise except that it had a coach-box, or seat for a driver, so postillions were not needed on the horses.

Mrs. Jennings had a chariot as well as a chaise. This shows that she was quite a wealthy as she could afford both vehicles and the horses and staff for a woman theoretically living alone. The dowager Mrs. Rushworth “removed herself, her maid, her footman, and her chariot, with true dowager propriety, to Bath” soon before her son’s rather ill-fated marriage. Mr. and Mrs. John Dashwood also owned a chariot, so it must have been the height of fashion.

The Landaulette

The landaulette was a small two-passenger, four wheeled vehicle with a top that folded back. Anne Elliot, once finally reconciled and married to Captain Wentworth owned “a very pretty landaulette.” These were normally pulled by two horses, so a very generous gift of independence by the Captain to his new wife!

The landaulette was a small two-passenger, four wheeled vehicle with a top that folded back. Anne Elliot, once finally reconciled and married to Captain Wentworth owned “a very pretty landaulette.” These were normally pulled by two horses, so a very generous gift of independence by the Captain to his new wife!

The Barouche

The barouche was a vehicle very much enjoyed by the aristocracy. The Oxford English Dictionary refers to barouches used by a duchess, by titled ladies, and by dowagers. The carriage looked quite light but that was deceiving as in fact it required very heavy bracing and was pulled by four horses. In Sense and Sensibility, the Palmers owned a barouche and Fanny Dashwood wished her brother, Edward Ferrars, would own one to be smarter! In Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford (certainly not a titled lady or dowager!) makes much use of his barouche and Lady Dalrymple in Persuasion also owned the same equipage. The most famous owner of the barouche must be Lady Catherine de Bourgh who generously offers a place in hers to Elizabeth Bennet, shifting her servant to the box seat.

The Barouche-Landau

The Oxford English Dictionary has no separate entry for “barouche-landau” and its only reference is the quote from Emma. However, the Morning Post newspaper of the 5th January 1804 announced that ‘Mr. Buxton, the celebrated whip, has just launched a new-fangled machine, a kind of nondescript. It is described by the inventor to be the due medium between a landau and a barouche, but all who have seen it say it more resembles a fish-cart or a music-caravan.’

I must believe that Jane used this carriage as an insult to Mrs Elton in Emma. Was this carriage generally received as a joke? Did Jane purposely give the Sucklings this carriage for Mrs Elton to wax lyrical over? The author does not name many carriages in Emma but she mentions the barouche-landau four times in a single monologue of Mrs Elton’s.

I hope you have enjoyed this journey through the world of carriages in Jane’s time. I have always believed that Miss Austen never wasted a single word in her writing and, after my research; I believe she also thought very carefully about the recipient of each type of vehicle in her novels. The readers of her day needed no explanation as to why Mr. Darcy drove a curricle and Mr. Collins a gig but, as modern readers, a little knowledge in this area gives us much greater understanding and raised even higher my already exalted estimation of Captain Wentworth with his gift to Anne of the landaulette!