Dinosaurs or Dragons

For my birthday, my hubby took me to a special exhibit at our local Museum of Natural Sciences. Naturally, we had to stop by the paleontology room to see the dinosaurs as well.

Naturally.

Standing amid the skeletons, it isn’t difficult to imagine dragons there. (I need to check in with the Dragon Sage and see if there is any shared ancestry between dinosaurs and dragons, but I digress.)

Nonetheless, the latest book had me asking what happens when dragons and dinosaur fossils coexist, as the setting was squarely in England’s Jurassic Coast, a hot bed for fossil hunting. Looking into what they knew about fossils during the Regency Era led me to this fascinating woman, Mary Anning (1799-1847), arguably one of the greatest fossil hunters.

Mary Anning

Sketched June 1842 by W. H. Prideaux and Edward Liddon

The round table for the fossils used to stand in front of the open cellar window which was a work shop.

Cockmoil Square. Public Domain

Born in Lyme Regis, in Dorset, Mary Anning grew up fossil hunting with her father, a cabinetmaker and carpenter who supplemented his income by finding fossils in the region’s Blue Lias and Charmouth Mudstone cliffs He sold them to tourists looking for vacation souvenirs to line their cabinets of curiosities. Now called the Jurassic coast, this region is unique as it is the only visible and accessible coastline that sports fossil bearing rock layers from the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous ages, the ages when dinosaurs roamed.

Early Education

Of her parents’ ten children, only Mary and her older brother Joseph survived into adulthood. She and her family were religious dissenters. Their Congregationalist doctrine emphasized education for the poor, so she learned to read and write in her Sunday School.

From this foundation, she taught herself geology, paleontology, and anatomy. From her readings, she learned how naturalists made deductions from their observations and how museums prepared specimens for display. Through practice, she became an expert in removing fossilized bones from rock and reconstructing skeletons. She learned how to draft scientific illustrations and often copied scientific literature and drawings for her own personal library. Later, in her 20s, Mary taught herself French in order to read the works of Curvier, the great French anatomist and father of paleontologist.

A professional fossil hunter is born

Mary’s father died in 1810, when she was 12 years old, leaving the family destitute. After selling a large ammonite fossil for more than any of her father’s fossils had sold, Mary realized she could help support her family and pursued collecting and selling fossils in earnest.

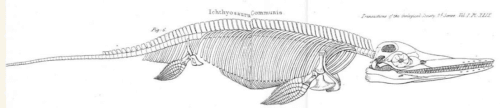

In 1811, she and her brother, Joseph, dug up a 4-foot-long ichthyosaur skull. A month later, Mary found the rest of the 16-foot skeleton, (arguably) the first ever complete ichthyosaur (fish-lizard) Temnodontosaurus platyodon, found in the region.

The huge skeleton took months to excavate, but she sold it to a collector for £23, the equivalent of six months of her father’s wages. Eventually that specimen ended up on display in the British Museum (1819) and threw the scientific world into an uproar with its support of Cuvier’s recently introduced theory of extinction.

Her discovery formed the basis for the first ever scientific paper written about the ichthyosaur, by Everard Home (1814). An illustration of the ichthyosaur skeleton appeared in William Buckland’s book Geology and Mineralogy (1836).

Between 1815 and 1819, she found several more ichthyosaur skeletons, which found their way to local museums or lecture circuits. Unfortunately, Mary never got credit for those finds, just the proceeds from the sales, which were sometimes as much as £100–£200.

Hard times were never far from their door, though. By 1820, it had been nearly a year since Mary had found anything significant and the family started selling their household goods to pay their rent. Thomas Birch, a local naturalist who had bought many specimens from Mary, decided to help the family. He went to London where buyers offered top prices to auction off many of the finds he had purchased from Mary. He gave Mary and her family the proceeds, providing them with much needed financial stability.

By 1827, she had made enough money from her fossils to purchase a house with a storefront which became known as Anning’s Fossil Depot.

Significant Dinosaur Finds

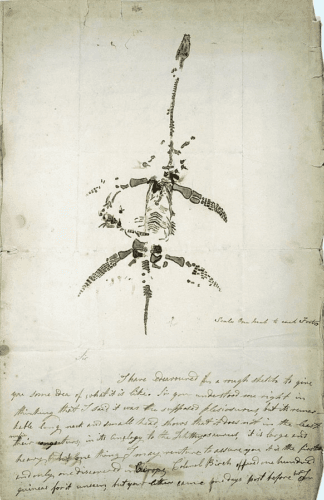

Source https://wellcomecollection.org/works/cezbevj4

In 1823, Mary she found the first complete plesiosaurus skeleton, Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus. Eight or nine feet long, and four feet from fin to fin, with a narrow snake-like head and four flippers, it looked rather like modern depictions of the Loch Ness Monster (which we all know was actually a dragon, again I digress…)

The creature was unlike anything known in the modern world. So strange that Cuvier himself disputed the find, declaring the fossil a fake. A special meeting of the Geological Society of London, with a huge attendance that did not include Mary, who had not been invited, debated the merits of the fossil. After a lengthy debate, Cuvier admitted he had been mistaken.

Many believe that Darwin was later influenced by the uniqueness of this specimen as he developed his theory of evolution via natural selection later in the century.

In 1828, Mary discovered the first pterosaur (winged reptile), Dimorphodon macronyx, outside of Germany. William Buckland later wrote about this and other pterodactyls in his work, Geology and Mineralogy considered with Reference to Natural Theology (1836).

In later years, Mary found several more important plesiosaur and ichthyosaur skeletons.

Other Significant Contributions

Mary’s discoveries were not limited to dinosaurs. She discovered new species of fish including the fish Dapedius sp., the shark Hybodus, and primitive chimaera fish Squaloraja polyspondyla.

She recognized the presence of the ink sacs in Belemnoidea fossils, 10-armed creatures that could squirt ink into the water, similar to modern squid or cuttlefish. The ink inside the sacs survived fossilization and artists in Lyme used it to sketch pictures of local fossils.

Working with Buckland, she discovered the true nature of coprolites as fossilized animal feces, identifying them in the abdomens of ichthyosaurus skeletons. Studying these coprolites offers scientists an opportunity to understand the diets of these animals.

The Inspiration for Paleoart

Her discoveries stimulated more than just scientific research. Inspired by her findings, geologist and childhood friend Henry De La Beche painted ‘Duria Antiquior – A More Ancient Dorset’ in 1830. The image portrayed the first graphic representation of prehistoric life based on fossil evidence, including ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs based on Mary’s findings. The newly invented art form is now called palaeoart.

With Mary still struggling to make ends meet, De la Beche gave her proceeds from sales of this print.

Recognition from the Scientific Community

As Mary continued to collect fossils, her skills in recording and preparing fossils grew. Museums and collectors sought her specimens. The scientific community, though, was hesitant to recognize her work.

She never published a scientific paper of her own, although she provided a great deal of research that others, like William Buckland and Richard Owen, used for their own scientific works. The sciences were not accepting of women’s contributions, even though geologists of the day generally extended her their respect.

Mary’s lower-class background and lack of formal education also presented insurmountable issues, as it was thought that commercial interests, like selling fossils, sullied the pure search for knowledge. A fact Mary resented, noting to her friends “…the world has used her ill and she does not care for it, according to her account these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal by publishing works of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages.” (Lang, 1955, p. 147)

Still, she was not entirely without recognition. In 1838, William Buckland convinced the British Association for the Advancement of Science to give her an annuity of £25 per year, in return for her many contributions to the science of geology.

Death and Legacy

In 1845, Anning was diagnosed with breast cancer. Geological Society members started a fund that paid for her treatment. The following year, the Dorset County Museum made her their first honorary member. When she died, in 1847, The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London published her obituary, an honor never before given to a nonmember. (The Geological Society did not admit women until 1904)

She was buried in the churchyard of Lyme Regis Parish Church.

During Anning’s lifetime, Louis Agassiz, a Swiss paleontologist, named two species of fish in her honor: Acrodus anningiae in 1841, and Belenostomus anningiae in 1844. Additional namings include: the therapsid reptile genus Anningia, the bivalve mollusc genus Anningella, the plesiosaur genus Anningasaura, and the Ichthyosaurus anningae species.

In 2010, the Royal Society recognized Mary Anning as one of the ten most influential British women in the development of science.

Today, her fossils are on display at the Natural History Museum in London. You can see one of her finds here:

And finally, a Dragon Connection

The plesiosaurus Mary found inspired geologist Thomas Hawkins’s Book of the Great Sea Dragons (1840).

References

Daring to Dig: Mary Anning. Museum of the Earth. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.museumoftheearth.org/daring-to-dig/bio/anning

Davis, Larry E. (2009) “Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology,” Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14

Eylott, Marie-Claire. Mary Anning: the unsung hero of fossil discovery. Natural History Museum. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/mary-anning-unsung-hero.html

Kaufman, Rachel. Mary Anning: Life and discoveries of the First Female Paleontologist. Live Science. February 22, 2021. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.livescience.com/who-was-mary-anning.html

Lang, W. D., 1955. Mary Anning and Anna Maria Pinney. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, v. 76: 146–152.

Mary Anning. Famous Scientists. https://www.famousscientists.org/mary-anning/

Mary Anning: Paleontologist. AWI. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://awis.org/historical-women/mary-anning/

Mary Anning’s House. Lyme Regius Museum. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://www.lymeregismuseum.co.uk/museum-at-home/mary-annings-house/

Newman, Cathy. Mary Anning: Daring to The Forgotten Fossil Hunter who Transformed Britain’s Jurassic Coast. National Geographic. March 29, 2021. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/mary-anning-forgotten-fossil-hunter-british-jurassic-coast

O’Connor, Madeleine. Women in Science-Mary Anning. The Oxford Scientist. December 19, 2018. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://oxsci.org/women-in-science-mary-anning/

Zielinski, Sarah. Mary Anning, an Amazing Fossil Hunter. Smithsonian Magazine. January 5, 2010. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/mary-anning-an-amazing-fossil-hunter-60691902/

Thank you so much for this post, Maria. I’ve been a fan of Annings since reading Tracy Chevalier’s book Remarkable Creatures over a decade ago. Her story is, like so many women who contributed to the scientific world in centuries past, a sad one. I hope your post will spark others to read more about her on their own.

Interesting post, reminding me that I really do need to hunt up a biography of Mary Anning.

Like you, I find myself constantly looking into the history or background of different persons to find out how they arrived to the point of being well known in their field study or specialty. Thank you for such an interesting read. It does my heart good to see women of past centuries being publicly recognized for the knowledge and contributions to our world.

Pingback:Down the Rabbit Holes of 2023 - Random Bits of Fascination